views

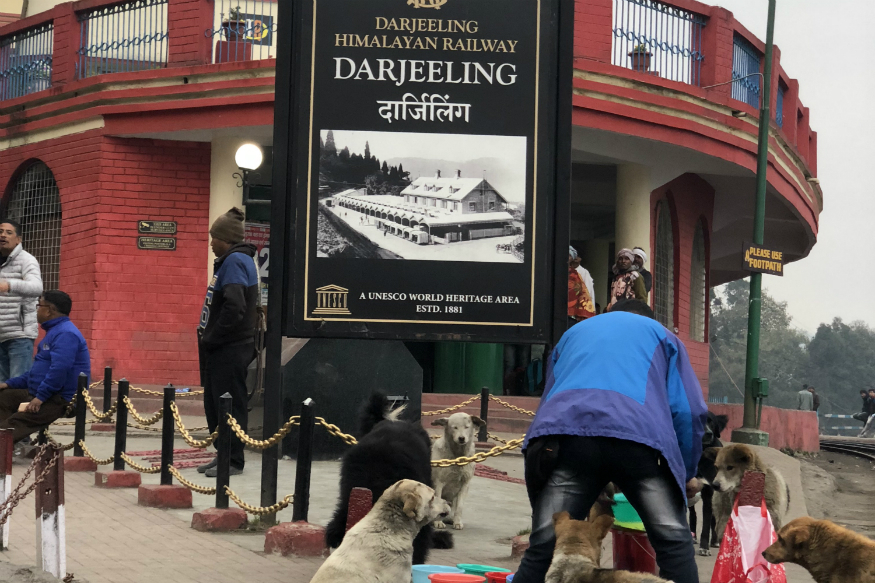

Darjeeling: There are two Darjeelings. One, the picture postcard variety, where tourists squint to catch a glimpse of the elusive Kanchenjunga. The other, closer to the ground, is of unmet aspirations and a century-old fight for identity, marred by continued political disappointment.

The memory of the 104-day agitation for Gorkhaland in 2017, led by Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJM) chief Bimal Gurung, which left 13 dead is still fresh. So is the anger at West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee for her alleged crackdown and BJP MP SS Ahluwalia for his “absence during the agitation”.

As Darjeeling prepares to vote on April 11, in what is in many ways an unusual and critical election in the state, it is the manner in which the strike ended that rankles most. The hills were left, not with the dream of autonomy that they had been promised, but with unpaid salaries, crippling bank installments, rotting agricultural produce, locked tea gardens and bad reviews that crippled the tourism industry.

Consider the stakes, the schism in the GJM that has dominated the politics here for the past decade offers Mamata a rare opportunity to complete her electoral dominance in the state. For the BJP, with its plans of expanding in Bengal, the importance of retaining the seat that first opened its account in the state goes beyond simple electoral arithmetic.

But for the people of Darjeeling, the agitation and the political machinations that have followed, have left them with a near impossible choice: to vote for a party that promises development but rejects any call for ‘Gorkhaland’ or the one that has promised statehood but has seemingly failed to deliver for nearly a decade.

As Binod Pradhan (19), a first-time voter who is studying at a government college put it, it boils down to the enduring question of identity. “Development is important. We need jobs, we need better access to education, drinking water and healthcare. We need land rights. The tea garden workers need to be able to live with dignity. But the fact is, if I venture out of Darjeeling, I am branded a Nepali. Identity seeps into everything,” he said.

Writing on the Wall

In 1952, CPI leader and legislator Biren Banerjee suggested a provision to provide regional autonomy within the West Bengal state for Nepalese speaking people. Although, this was opposed by the-then chief minister Bidhan Chandra Roy, it was, as per historian Subhas Ranjan Chakrabarty, possibly the first time that the phrase of “regional autonomy” was used in the context of the hills.

Transferred to the East India Company by the Raja of Sikkim in 1852, Darjeeling and its people were shaped by British commercial and strategic interests. The tea gardens, the army and the possibility of employment attracted migrants, not just from Nepal but also from Terai region and the plains. With time, settlers shed their tribal identity in favour of an inclusive Nepali identity and in 1907, a memorandum was presented on behalf of the hill people of Darjeeling for a “separate administrative unit” for the district. Almost immediately after 1947, an agitation for a linguistic state separate from West Bengal began.

A board outside a shop that reads 'State: Gorkhaland'

Over the years, the quest for autonomy was frustrated with Delhi remaining wary of the Nepali language nationalism (with Nepal a next-door neighbor and the narrow 22-km Siliguri corridor connecting the mainland to the north-east) and Kolkata unwilling to part with the revenue that Darjeeling earned through tea and tourism. All this appeared to change in 2009, with the BJP promising “sympathetically consider the longstanding demands of the Gorkhas, the Adivasi and the people of the Darjeeling district and Dooars region to form a separate state in India” in its election manifesto. The BJP won with over 51% of the votes and then again in 2014 with 42% of the votes.

This year promises to be different. In his rally in Siliguri last week, the first in Bengal, Prime Minister Narendra Modi stayed silent on the statehood issue - something his supporters didn’t miss. “We thought that SS Ahluwalia remained silent on the issue because he shared the same biases as the rest. But it is disappointing that PM Modi didn’t speak of Gorkhaland,” admitted Deepak Pradhan, a taxi driver.

Caste Fault Lines and Mamata’s Change in Tact

Since 2011, the Trinamool government in Bengal has worked diligently to woo the different minority ethnicities in the hills. To begin with, Banerjee created six boards - for the Lepcha, Tamang, Rai, Sherpa, Butia and Mangar communities and by the 2016 Assembly elections, there existed 15 such boards. Although the TMC didn’t win any seat in the Assembly in the hills, it emerged as the second-largest party. In 2017, it won the Mirik municipality in Darjeeling district, the first ever in three decades that a non-Gorkha party has won in the area.

In doing so, Banerjee also exposed the caste fault lines that exist in the Gorkha community, especially after the creation of three separate development boards for the Kamis, Damais and Sarkis (numbering nearly 80,000 as per the 2001 census). “The political parties allege that Banerjee has been using ‘divide and rule’ to break down the Gorkha identity. Maybe that is true. But she didn’t create the divide, it already existed,” said Bijay, who belongs to the Kami community and lives in Kalimpong.

The polls, for now seem to be a binary contest after the split in GJM: between TMC’s Amar Singh Rai (a former GJM legislator) supported by the GJM faction led by Binay Tamang and Raju Bista, the BJP candidate supported by not just Gurung, but also bitter rivals Gorkha National Liberation Front (GNLF)

But with neither Bista nor Rai openly campaigning on the issue of Gorkhaland and Modi silent on the Gorkhaland issue, it is tempting to conclude that the issue has taken a backseat. A walk through Darjeeling proves otherwise. Shops and homes declare their addresses to be in “State: Gorkhaland” and posters from the movement stating “We want Gorkhaland” only partly ripped apart by the district administration.

Significantly, on Friday Banerjee changed tact. She assured Gorkhas that their issues of identity would be taken care of at an election rally at Naxalbari in Siliguri. “I want to promise that the identity of Gorkhas would be taken care of…but you should realize that the BJP had said that if you voted for them, they would give you Gorkhaland. However, after taking votes from you, they went to Delhi and did nothing for you,” she said, while listing out developmental works her government has carried out in the state and portraying an image of unity.

BJP leaders argued that the promise by Banerjee, who has remained steadfast in her stand that “Darjeeling is an integral part of Bengal”, was prompted by the possibility of the “major victory” of Gurung campaigning for Bista in Darjeeling.

Meanwhile, at Ghoom, a small hilly locality in Darjeeling, Shanti Tamang (48), who runs a small eatery, remained unimpressed. “There are those who have benefited from Didi’s policies. But the question of identity goes deeper. She is in a position to actually do something about the issue of identity. Right now, I am not sure if she can be trusted. But then, there are others who feel the same way about the BJP.”

Comments

0 comment