views

While responding to the failed no-confidence motion against his government on the ‘Manipur issue’, Prime Minister Narendra Modi taunted members of the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in Tamil Nadu that it was their leader, the late M Karunanidhi, as Tamil Nadu chief minister, who acquiesced to Congress ally ruling the Centre to palm off the tiny Katchatheevu islet to neighbouring Sri Lanka. As was to be expected, this has triggered a peripheral reaction in Sri Lanka that PM Modi was indulging in ‘double-talk’, implying he wanted India to take back Katchatheevu.

If mainline parties in the island nation have not commented on Modi’s observation, it also owes to the all-round support India has been extending since the unprecedented economic crisis hit Sri Lanka last year. During the immediately preceding Covid pandemic across much of the world, New Delhi voluntarily took over the responsibility of helping out all neighbouring nations, first with testing kits and medical equipment, and later with the homemade vaccine, even before it had supplied enough for Indians.

At one stage in the pandemic fight, India even despatched ‘oxygen ships’ to Sri Lanka, just as it had sent ‘water ships’ to common neighbour Maldives, when at the end of 2014, the capital Male went thirsty after a fire in the sole desalination plant for the city, as part of its self-conscious ‘R2P’ (Responsibility to Protect) commitments to the neighbourhood since long before the UN coined the term in 2005.

Huge canvas

Modi’s reference to Katchatheevu comes at a time when the two nations have begun working on a huge canvas for bilateral economic cooperation. Alongside ambitious projects for underwater petroleum pipelines and electricity cable connections, Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe’s dream-like project for road linkage between the two nations is also up for preliminary surveys, leading up to their completion. The two sides signed an MoU on the land bridge, along with those for the pipelines and cable connections, among others, during Wickremesinghe’s recent visit to New Delhi.

He had first proposed the land bridge during his second of five innings as PM. In 2003, he flagged the idea first at a Chennai seminar and later in talks with his Indian counterpart, Atal Behari Vajpayee. It did not progress because of stout protests from Tamil Nadu’s former CM Jayalalithaa-led AIADMK government. She claimed that owing to the existence of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) (and its deadly ‘Sea Tigers’ wing), the project would be a ‘security threat’. The state government refused to be a part of the planned surveys for the land bridge at the time.

Though directly not interlinked in technical terms, any perception of India’s changing position on Katchatheevu could jeopardise its own plans for finding permanent solutions to the fuel crisis in Sri Lanka, which topped the list alongside the dollar crisis, last year. The land bridge, likewise, will help increase trade and tourism to Sri Lanka from India, which is already the top source of tourists to that country. Here already, there are those in Sri Lanka, who threaten their majority Sinhala people that the idea was to make their nation an Indian State or Province, as is known in that country.

UNCLOS Protection

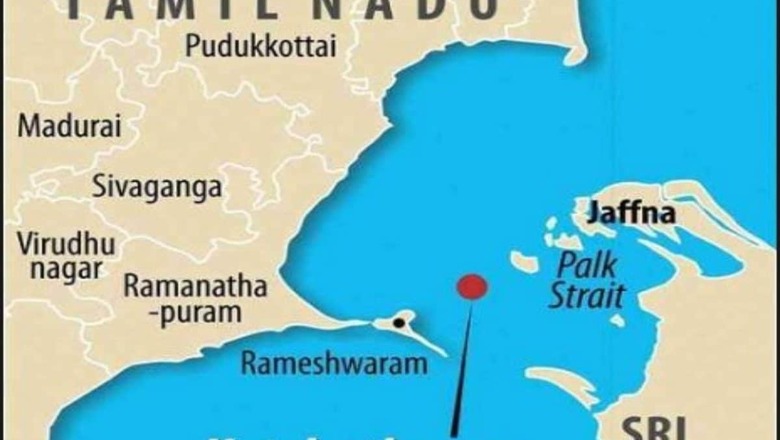

Katchatheevu is an uninhabited islet, just 285 acres in area, between the two nations, but closer to the Indian shores — 14 nautical miles from the temple island of Rameswaram. Traditionally, Tamil fishers from Tamil Nadu and their brethren from Sri Lanka’s Tamil North used the islet for resting and recuperation and also to fish in those waters. The greater attraction was/is the annual festival at the St Anthony’s Church in February/March, in which mainly Tamil-Christian fishers from the two nations participate. The island was shut down for fishers and others (not that there are other travellers) during the LTTE war in Sri Lanka when the nation’s navy took control.

This year, there was an avoidable controversy when the fisher-worshippers at the festival found a small statue of Lord Buddha — Buddhism being the religion of the majority Sinhala community in Sri Lanka — installed under the religiously significant peepal or Bo tree. After persistent questioning by the SL fishers, the Sri Lanka Navy (SLN) acknowledged that the Buddha statue was put up by one of their officers to facilitate their men who wanted a place for daily worship. However, under directions from the Colombo government, the idol was said to have been removed, since, this could have greater bilateral implications, too, than can be visualised.

The continuing controversy over Katchatheevu stems from a bilateral agreement between the two governments in 1974, followed by another, two years later in 1976. After working to identify their maritime territory through negotiations under UNCLOS-I, the two countries assigned the first accord, that Katchatheevu fell on the Sri Lankan side of international waters, as demarcated by them to the exclusion of any international intervention of the UN kind.

The UNCLOS itself is a UN mechanism, short for the ‘UN Convention on the Law of the Sea’, and joint notification under UNCLOS by parties to an accord of the Katchatheevu kind meant, and continues to mean, that it was final and sealed and cannot be reopened at will by either party to the accord, or others, say, ‘aggrieved Indian fishers’ from Tamil Nadu or anyone else on their behalf, starting with the Tamil Nadu government.

The Controversy

The 1974 accord provided for Indian fishers to fish in the Katchatheevu waters and also dry their nets, rest and recuperate. This clause was missing in the subsequent accord of 1976, which meant that traditional access that the TN fishers have had for generations and centuries could be denied to them. It came to a stage, especially after the end of the LTTE war in 2009, when the Sri Lanka Navy started patrolling the area, to keep ‘trespassing’ Indian fishers, as from other fishing grounds across the International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL) as agreed upon in 1974 and subsequently notified under UNCLOS.

The issue began assuming serious proportions only during the end years of the war when Indian fishers had relatively free access to Katchatheevu waters and also across the IMBL. Such access had been denied to the Tamil fishers of that country, owing to the LTTE threat and feared allegiance to the terror outfit with a deadly ‘naval presence’, all directed against the Sri Lanka Navy. But the real focus still was on the Palk Strait, where especially the Indian Tamil, and at times Kerala fishers, both based out of Rameswaram, ‘violated’ the IMBL accord, hence Sri Lankan ‘territorial waters’.

In a way, the Katchatheevu issue became a by-product of the larger fishers’ dispute, which was becoming bloodier by the day, owing to constant intervention by the SLN, as the ‘mandated guardian’ of the nation’s waters. Either the SLN had direct political directions, or they did so as mandated, but their interventions involved arrests and attacks on the Indian fishers in Sri Lankan waters, at times causing death when the navy personnel opened fire on innocent Indian fishers.

While the larger fishers’ issue is still raging, with its own periodic upward swings in terms of the number of arrests, etc, there has not been any major shooting incident involving the SLN personnel and Indian fishers, in the aftermath of a bilateral agreement to the specific effect in 2008 (towards the closing months of the ‘ethnic war’). Almost always calibrated to the fishers’ dispute, mid-sea arrests and attacks, in which the Tamil fishers of the Sri Lankan North, give the nation’s navy a helping hand.

History and Historicity

Truth be told, both India and Sri Lanka had claimed Katchatheevu as part of their territory even when ruled by the common British Crown but under different local administrations with independent Governors-General. On record, the islet was part of the Sivaganga principality under Ramanathapuram’s Sethupati Raja. According to academic researchers wanting to access these original documents, as they used to in the pre-Accord period, they have not been able to locate/lay hands on them. Some of them are on record that the Government of India had secured them to protect the sanctity of the 1974 agreement and the UNCLOS notification.

At the same time, prior to the agreement, since almost the beginning of the bilateral dispute from the British era, the then Ceylon government had produced documents claiming that Katchatheevu was a part of the northern Jaffna district, though distanced from the mainland than the Indian shores are. To support their argument, the Sri Lankan side has also referred to the tradition of a priest from Jaffna presiding over the annual festival and saying the Holy Mass. As they point out, none from India, again from the British days to the present, has questioned the practice, implying acquiescence to the ground reality.

When bilateral IMBL began to be negotiated under UNCLOS-I (negotiated in 1958), ‘median line’ was the general principle for marking the IMBL between two nations. In this case, however, the bilaterally-negotiated IMBL takes a sharp deviation, to include Katchatheevu as a part of the Sri Lankan maritime territory. It is this deviation of the median line that is often challenged by fishers and political interests, in Tamil Nadu, in particular. However, successive governments, including the incumbent Modi regime, have repeatedly announced in Parliament that Katchatheevu belonged to Sri Lanka, and cannot be reopened for re-negotiation.

What was essentially a fishers’ issue became a political topic especially after the then Chief Minister Jayalalithaa, in her maiden Independence Day speech from the ramparts of Fort St George, the seat of power in the capital Chennai (then Madras), demanded the Congress-ruled Centre of Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao to take back the islet, which was ‘wantonly given away’. In the state assembly and outside, she began blaming DMK predecessor Karunanidhi and the Congress rulers in Delhi for the ‘fiasco’ – a line that PM Modi too has now taken. If it was political then, it is political now, with the ruling BJP at the Centre not wanting to leave any stone unturned in its efforts to corner the Congress-DMK combine in the upcoming Lok Sabha elections next year.

Lapsed petitions

Even while being Chief Minister, Jayalalithaa also challenged the 1974 Accord in the Supreme Court, in her personal capacity. This was followed by DMK’s Karunanidhi moving the apex court, again in his personal capacity. The common ground in the two petitions was that the Accord, involving a change of the nation’s international border was not ratified by Parliament, as required under Article 3 of the Constitution. Both leaders, when in power, have caused the state assembly to pass resolutions that were mostly ‘unanimous’, thus reflecting the prevailing political and public mood in the matter.

However, the two petitions by Jayalalithaa and Karunanidhi, on which the court hearing was either slow or tardy, lapsed after the death of the two petitioners, respectively in 2016 and 2018. There is a sidelight though that may not mean much in legal terms. After returning to power in 2001, Jayalalithaa got the state government to implead itself in her petition, but not in Karunanidhi’s petition, which too was still alive on record. Karunanidhi, who returned to power in 2006, did not attempt to implead the state government in his petition, nor did he cause the state government to withdraw from the pending Jayalalithaa plea.

But is there a case there? Did the Government of India require Parliament’s consent for drawing the IMBL and letting Sri Lanka have Katchatheevu? The Accord was signed for the two countries by the respective foreign secretaries — Kewal Singh for India and W T Jayasinghe for Sri Lanka. The Indian government held the view that the maritime boundaries of the two countries had not been drawn all through history, hence there was no question of the nation ceding any territory to Sri Lanka. Hence, there was no need for approaching Parliament for post facto approval. The government considered this position in the Supreme Court, too.

Why the deviation?

Now comes the question of why did India acquiesce to the IMBL deviation, when it had a substantial case based on documents then available with the state archives, now supposedly in the Centre’s possession? There were both political and strategic reasons. Politically, not long after the Bangladesh War of 1971, India needed to assuage the scepticism and suspicions of other neighbours. Of them, Sri Lanka reportedly had the greatest of fears, for reasons unexplained to date. Even the ‘ethnic issue’ and India’s R2P engagement was a decade and more away.

In strategic terms, there is the hidden truth that the ‘IMBL deviation’ and the Indian acceptance of Katchatheevu ensured that there won’t be a small pool of ‘international waters’ in those seas, requiring the two nations to provide maritime access to third-nation vessels. Suffice is to point out that when India began toying with the idea of the ‘Sethusamudram Canal Project’ and Prime Minister Vajpayee laid the foundation, the US began claiming the ‘right to passage’.

That demand has not been repeated not because the US has changed its mind, especially after increasing political, security and military cooperation with India. Instead, it possibly owes to the project getting caught in the Supreme Court. Suffice is to point out that even last year, the US Navy asserted its ‘right to passage’ near the seas abutting the Lakshadweep island group, bilateral naval and larger military/security cooperation with India notwithstanding.

Of course, there is a section of the Sri Lankan strategic community that wants to willy-nilly link the Katchatheevu part of the 1974 Accord to another clause in the document, by which Sri Lanka gave away the ‘catch-right’ Wadge Bank, south of Kanyakumari, the nation’s land’s edge, as if ‘in exchange’. In India’s Cold War era, geo-strategic calculations of the time, the Wadge Bank in the Indian Ocean could provide free naval access to the nation’s adversaries, compared to Katchatheevu, which would be under the ownership and possession of a ‘friendly neighbour’.

While it is true that India had to sell/supply fish at subsidised rates for SL fishers depending on the Wadge Bank catch for three years, there is no similar clause pertaining to the Katchatheevu part – the Indian fishers should pack up and go after a fixed period. It was a deal in perpetuity. Yet, there is some logic to the informal Sri Lankan argument that the Indian fishers would have no need to dry their nets, which were made of nylon, unlike coir or cotton in the immediate past. That is yet theoretical with no legal sanction of any kind, but then there is no substantial catch in those waters as before, after years of over-harvesting by the Indian fishers, not just in those parts but all across the Palk Bay region.

‘Sea Lotus’ campaign

In this overall background, the BJP had flagged both the Katchatheevu and larger fishers’ issue across southern coastal Tamil Nadu, especially during the run-up to the 2014 parliamentary polls. Leaders like the late Sushma Swaraj, later External Affairs Minister (EAM), launched the ‘Sea Lotus’ (Kadal Thaamarai) campaign in Rameswaram, linking the fishers’ dispute to the party’s election symbol. Such efforts did not help the party electorally, then or since.

Hence, for PM Modi to touch on what is a sensitive issue in bilateral relations is still an electoral non-starter, even if repeated a thousand times even in the southern coastal belt. But it could kick off avoidable discomfort in ‘India-friendly’ Sri Lanka, especially for the government of the day and those in the future, as anti-India socio-political groups have a longer memory than New Delhi understands and acknowledges.

From inside Tamil Nadu, such statements as what Prime Minister Modi made in Parliament may not have any reference whatsoever to bilateral relations. But then, PM Modi can be wantonly misquoted in Sri Lanka, to delay, if not deny, the multiple connectivity projects that are already on the anvil — if any anti-India group so desires, without directly criticising an ‘ever helpful’ India, otherwise.

In Tamil Nadu, some fringe groups or electorally-failed leaders and parties can revive their forgotten call for the Centre to approach the International Court of Justice (ICJ), for ‘retrieving’ Katchatheevu, though it may have to remain a non-starter, otherwise. And thereby hangs the tale!

The writer is a policy analyst & political commentator, based in Chennai. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment