views

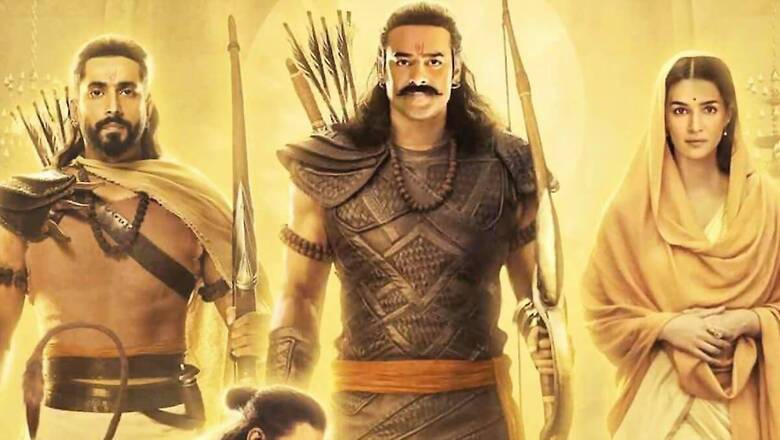

After its release last Friday, Prabhas’ Adipurush has taken the box office by storm, earning over Rs 300 crore worldwide in three days. But holistically looking at the film, it has been a case of failed promises. Of an imagination gone awry.

Adipurush could have been much more than just “a record-breaking film” at the box office. But then it became a victim of the makers’ lack of imagination — and ambition. One can accuse them of being content with plucking low-hanging fruits by turning the Ramayana into an extension of the Game of Thrones meets the Planet of the Apes — even here, the impact has been underwhelming given that the film’s special effects look obsolete and jaded in comparison with, say, Avatar and RRR.

Complementing the problem is the lack of reverence for the subject, despite PR optics like leaving a seat for Hanuman in each theatre hall. Yes, the film doesn’t fall into the ‘progressive’ trap of retelling the Ramayana from Ravan’s perspective, as Saif Ali Khan, playing the main antagonist’s character in the film, had initially claimed. (One can look at the fate of Mani Ratnam’s ‘modern’ interpretation of looking at the Ramayan from Ravan’s eyes.) But it definitely invades the sacred.

In the name of making a “massy” film — there cannot be a more mass-oriented stuff than Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan or SS Rajamouli’s RRR — the makers of Adipurush give “tapori” dialogues to Hanuman. It was disheartening to see one of most popular Hindu gods being reduced to a street-side comedian, uttering lines such as “Kapda tere baap ka, aag tere baap ki, tel tere baap ka, jalegi bhi teri baap ki”. Can anyone imagine Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru or Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose of using such lines for the British, who committed inconceivable horrors on this landscape in the name of “civilising a savage world” — a term which, ironically, Nehru’s niece Nayantara Sahgal uses for her book’s title to describe her uncle’s “achievements”? How can the lines that don’t seem to be appropriate for mortals, be acceptable for gods?

Maybe powerful mortals can exact revenge, take you to courts, and make you pay heavy price for your mischief, but not our ‘poor’ gods. Maybe that’s the reason why writer Manoj Muntashir could still defend the film’s dialogues, calling them the result of a “meticulous thought process”.

It’s an obvious and understandable exercise to contemporarise an ancient epic. The great Tulsidas did exactly the same when he wrote Ramcharitmanas thousands of years after the sage Valmiki’s Ramayana. Tulsi’s version was a contemporary version of Valmiki’s magnum opus. He wrote it for the masses of his times, catering to the needs of his era. But Tulsidas can never be accused of invading the sacred. If anything, he can be charged with being even more reverential to Ram and Hanuman. Mr Muntashir, you are welcome to contemporarise ancient texts, but don’t trivialise them.

The makers of Adipurush should look at Rajamouli’s films that invariably hit the bulls-eye not just because of their technical brilliance but primarily due to the reverential approach he adopts while dealing with the civilisational aspect of the storyline — a basic precondition that Bollywood fails to meet in the very first place. The two-minute Ram act in RRR has been visually more powerful and appealing than three hours of Adipurush: The difference being the manner in which the two films looked at Bhagwan Ram. While in RRR he is an unapologetically civilisational Ram, in saffron robe and with a serene, gentle bhava (expression), in Adipurush he is angry and agitated, wearing part-saffron, part-military gear.

Like the dress, which is part-saffron, part-military, Adipurush initially takes a reverential path but half way through the journey it makes a U-turn. It suddenly becomes conscious of its contemporary needs — and the film becomes a messy mix of the old and the new, with no character of its own. But why just Bhagwan Ram or Maa Sita (who again has been glamorised enough to confuse the watchers if she were in the jungle for honeymoon), even Ravan is not the Ravan of the Ramayana.

Adipurush’s Ravan is not Valmiki’s Ravan. He appears to be shaped more in the Alauddin Khilji mould — sadistic, cruel, and evil personified. The idea of Ravan being an evil incarnate is a relatively modern phenomenon. Traditionally, the worshippers of Ram also hold Ravan in high esteem. This respect for Ravan has its roots in the Ramayan itself: When Ravan, after being wounded, was awaiting his death, Ram asked Lakshman to pay him a visit and take lessons from him. When Lakshman went to meet Ravan, the latter even refused to acknowledge his presence. An angry Lakshman came back to Ram, who asked him where he stood while seeking wisdom. “Next to his head,” replied Lakshman. Ram smiled and walked towards Ravan. Placing his bow on the ground, he knelt at Ravan’s feet and requested him to share his wisdom. Ravan immediately acceded to the request.

The Sanatana worldview desists and detests looking at people and events in black and white. It is this civilisational nature of India that makes it the land of possibilities — of dialogue and diversity. Here diversities and differences are not just accepted but often celebrated. This explains why so many Ramayanas co-exist and thrive in India. Why Ravan was neither an evil incarnate, as Adipurush wants us to believe, nor an outright victim, as was showcased in an old Mani Ratnam film by the same name. In this eternal Sanatana order, Ravan can be respected for his superhuman achievements and yet his Icarus-like fall is annually celebrated as a cautionary tale of what happens when ego gets the better of intellect.

If lessons learnt, Prabhas’ Adipurush can be a good beginning for Bollywood, currently stuck with many failures and very few successes: That the film industry doesn’t need to look Westward for ideas. India has always been the land of fascinating stories. What the filmmakers need to do is to stop blindly aping the West, to stop ridiculing Indian sensibilities, to stop being judgemental about Indian mores, and, above all, to stop being apologetic about being Indian. This is India’s century — with or without China. It’s time we understood this and behaved accordingly, with grace, wisdom and confidence.

The author is Opinion Editor, Firstpost and News18. He tweets from @Utpal_Kumar1. Views expressed are personal.

Comments

0 comment