views

Beginning Your Essay

Read your assignment carefully. Review the prompt and ensure you clearly understand the assignment. Look for keywords such as “analyze,” “explain,” and “compare and contrast.” These words will let you know exactly what your essay needs to accomplish. For example, “analyze” means to pull apart. The prompt “Analyze a poem by Charles Baudelaire” is asking you to divide a poem into specific elements and explain how they function. Note any details such as “Compare and contrast 2 short stories not discussed in class.” Discuss the similarities and differences of your examples' literary devices, and be sure to choose stories that weren't covered in class. Your assignment instructions may include a breakdown of how your work will be graded (e.g., a certain number of points may be awarded based on organization, spelling and grammar, or the strength of your sources). If the grading criteria aren't clearly explained in the instructions, ask your teacher or professor to explain their rubric. If any part of the prompt seems unclear or confusing, don't hesitate to ask your professor for help.

Compile your sources and evidence. An academic essay needs to support its claims with solid evidence. Head to your library, hit the books, and surf the web for credible, authoritative sources on your topic. You'll likely need to include primary sources, such as the poem or story you're analyzing, or letters written by the historical figure you're discussing. Secondary sources, such as scholarly articles or books, are publications by experts on your topic. Cite secondary sources to back your argument, or mention a source in your counterargument to refute the claims of its author. If you have trouble tracking down good sources, ask a librarian or your professor for help. Your course syllabus likely includes useful texts, too. Check their reference or further reading sections for additional leads. Your school or university library likely subscribes to academic research databases like EBSCO and J-STOR. Log in to your library's website to access these resources. You can also use free online resources like Google Scholar.

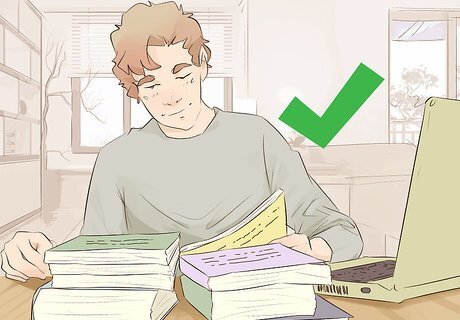

Brainstorm to come up with ideas. Now that you've done your research, you're ready to put together some ideas for your essay. There are lots of ways to brainstorm, and you'll probably find that you prefer one over others. In any case, it's best to jot down your ideas by hand when you brainstorm instead of keeping them all jumbled in your head. You could write down main ideas or keywords in bubbles or clouds. Draw lines between connected concepts and make smaller bubbles for terms connected to larger ideas. Bullet point lists could help you gain a bird's-eye-view over your material. For a literary analysis, you could list examples for categories such as “Literary Devices” or “Key Events.” Try journaling or free-writing to get your creative juices flowing. Write what you know about the topic for 15 or 20 minutes without censoring your ideas.

Organize your ideas into an argument. Review your prompt, brainstorming materials, and research notes. Write down a few main ideas you want to focus on, then revise those ideas into an assertion that responds to the essay prompt. Try to find an overarching argument or idea that encompasses all the major points you want to address. Suppose you need to compare and contrast 2 literary works. You've analyzed each example, and you've identified how their elements function. They both employ nostalgic appeals to emotion, so you'll assert that the works use similar persuasive strategies to advance opposed ideologies.

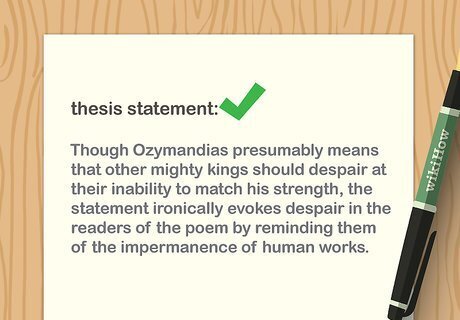

Come up with a concise thesis statement. Refine your argument into a clear and concise sentence, which will serve as your essay's thesis. While your thesis will help you stay on track through the drafting process, bear in mind you'll likely tweak it as your essay evolves. You'll include your thesis in the introduction. It lets the reader know exactly what you're trying to prove. Note that you should just write your claim; don't start your thesis with “I will prove that,” or “It will be shown that.” Early in the drafting process, your working thesis could be “Charles Baudelaire's experiences of city life and travel abroad shaped his poetry's central themes.” As your essay takes shape, refine your thesis further: “Drawing on experiences of urban life and exotic travel, Charles Baudelaire reinterpreted la voyage, a primary theme of French Romantic poetry.”

Drafting Your Paper

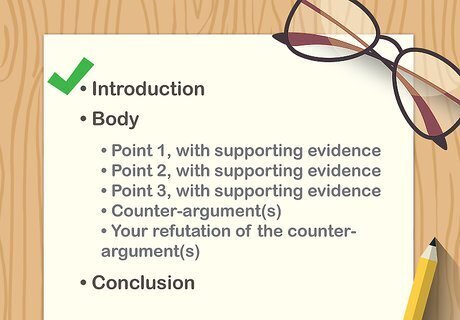

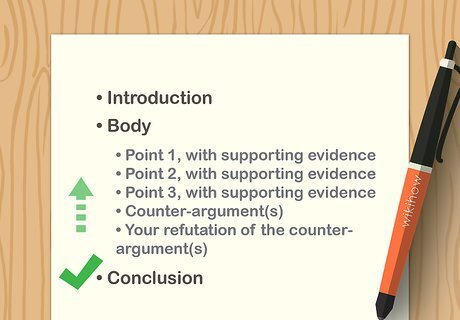

Outline your essay's structure. Write out your thesis on the top of the page, then list Roman numerals (I., II., III., IV.) or letters (A., B., C., D.) for the body paragraphs or sections. Add each paragraph or section's main idea, write bullet points or numbers (1., 2., 3.) under the section, then fill in supporting details next to the numbers. It's also helpful to plug in your sources and citations where you plan on using them. For instance, next to section III-B-3, write the source you plan on citing, e.g., “Smith, French Poetry, p. 123.”

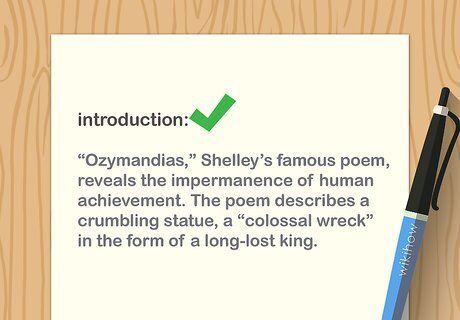

Write your introduction. Depending on your assignment, you might start off with an attention-grabbing topic sentence. However, it's common for academic essays to get straight to the point and put the thesis front and center. The sentences after the thesis then map out the rest of the essay, which lets the reader know what to expect in the coming paragraphs. The road map should mention the evidence you'll use to prove the thesis. For example, “Analyses of the key poetic elements, along with discussion of autobiographical excerpts, will show how Baudelaire imagined la voyage as darker and more complicated than his Romantic predecessors.” Some people prefer to write the introduction before making an outline. Do whichever feels more comfortable. Your outline could help you structure your introduction, or your intro might lay out a road map for your outline.

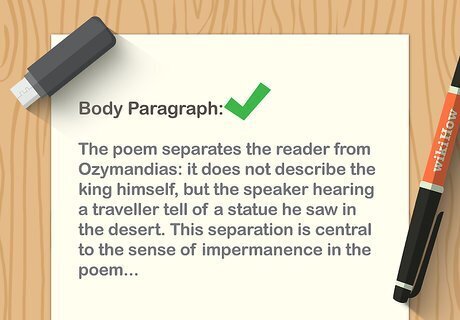

Fill in your body paragraphs. Now comes the grunt work! Working section by section, put together the pieces of your argument. Transitions are key, so make sure your paragraphs and sections are logically connected. In high school, you probably learned to write a basic essay with an introduction, 3 body paragraphs, and a conclusion. That structure won't work if your argument calls for a more complex structure, or if your paper needs to be 10 or 15 pages. For instance, in the first 2 or 3 paragraphs after the introduction, you'd need to discuss how la voyage was a recurring theme in French Romantic poetry in the 19th Century. After establishing how other poets handled the theme, the next logical step is to describe Baudelaire's conception, and to support this description by citing his poetry. Since the thesis argues that this conception owes to his personal experiences, you'd then discuss how city life and travel abroad shaped Baudelaire's poetry.

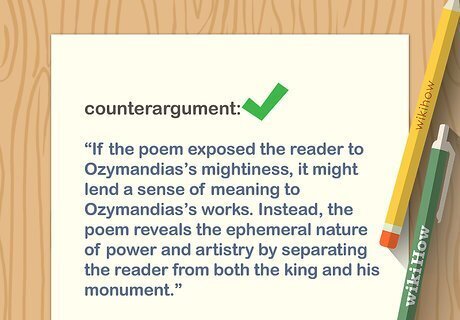

Strengthen your claim by addressing a counterargument. While you won't always need a counterargument, including one makes your thesis more convincing. After building your argument, mention an opposing viewpoint. Then explain why that perspective is incorrect or fails to prove you wrong. Suppose you've argued that a military conflict was caused by increasing nationalism and competition over resources. A scholar previously claimed that the conflict was solely instigated by the involved nations' authoritarian governments. You'd mention that this argument ignores the underlying tensions that set the stage for the conflict. Good ways to address a counterargument include refutation (where you provide evidence that weakens or disproves the opposing perspective) and rebuttal (in which you offer evidence that shows that your argument is stronger).

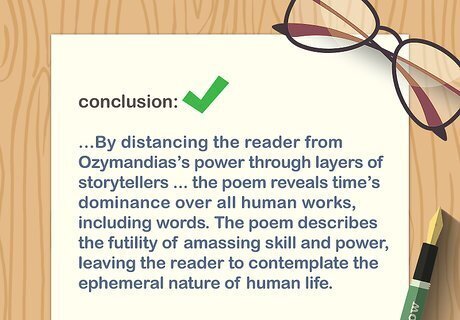

Pull your points together in your conclusion. A strong conclusion does more than simply repeat the introduction's content with different wording. While you should restate your thesis and remind the reader of your evidence, you should also offer a resolution. Provide an insight, broader implications of your argument, or a practical way to apply the information you've gleaned. For instance, if you argued about how a rising tide of nationalism led to a military conflict, you could write, “Unwillingness to find diplomatic solutions, bolstered by the belief of national superiority, led to this particular conflict. So too, on a global scale, rising tides of nationalism threaten the political and economic bonds of the international community.”

Revising Your Draft

Read your essay draft out loud. As you read, listen for awkward phrasing, convoluted sentences, and abrupt transitions. Mark spots that seem odd or off to your ear, then go back and work on making them smoother. As you read, consider whether each of your body paragraphs fully supports your thesis. It's helpful to print a copy of your essay so you can write notes and corrections by hand. Additionally, take a break before you begin revising so you can approach your work with fresh eyes.

Write a reverse outline. As you read, create an outline based on your essay as written. E.g., you might pull out or summarize the topic sentence of each paragraph, then write out the major supporting ideas as bullet points after each topic sentence. This can help give you a better sense of your structure and help you come up with ways to improve it. For example, when you see your essay in outline form, you might realize that the essay would flow better if you changed the order in which you present your main points.

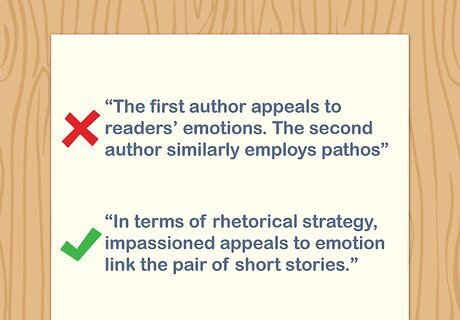

Switch up your sentence structures. Look for any spots where your sentence structures get repetitive. If necessary, add variety to your phrasing to make your essay more engaging and readable. The sentences, “The first author appeals to readers' emotions. The second author similarly employs pathos,” are boring and repetitive. A better structure could be, “In terms of rhetorical strategy, impassioned appeals to emotion link the pair of short stories.”

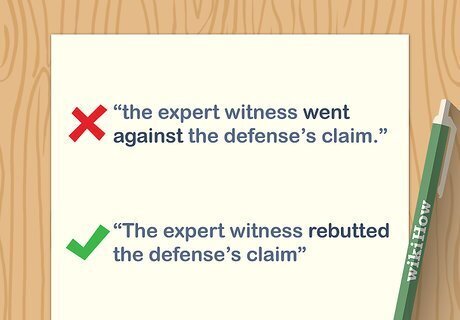

Make sure you've chosen strong, clear words. Ask yourself if you've overused any words, and make tweaks if you need more variety. Additionally, look for any occasions where you should replace a word with a stronger, more precise alternative. Be sure you've used strong, clear verbs. “The expert witness rebutted the defense's claim,” for instance, is stronger than “The expert witness went against the defense's claim.” Double check that you've used the active voice whenever possible. “Baudelaire defined our understanding of modernity,” is stronger than the passive construction, “Modernity was defined by Baudelaire.”

Fix any typos, spelling mistakes, or grammatical errors. Do a final close reading of your essay, and correct any errors you find. Again, it's helpful to take a break before doing a final check. It's easy to miss minor errors after you've been staring at the essay for hours. Be sure to spell check with your brain and not your computer. Your computer probably won't catch a “wear” used instead of “where.”

Have someone else proofread your essay. Once you're done, ask a someone else to review it, such as a friend or a tutor at your school's writing lab. A fresh set of eyes will prove valuable, and someone approaching your essay for the first time might see things you overlooked. Ask the person to look for more than just spelling and grammatical errors. Have them offer feedback on your argument's structure, and ask them to point out any spots that seem unclear or under-developed. If necessary, revise your essay once more to apply their suggested changes.

Comments

0 comment