views

X

Research source

Reading Chord Charts

Find the chord chart. Normal sheet music would have the exact notes of the chord symbolized on the staff. With a chord chart, you just have a series of letters and numbers that represents each chord. The name of the chord tells you how to build the chord on the piano. It gives you information about which keys to put your fingers on to play that chord.

Identify the root note of a chord. On a chord chart, the root note is the first capital letter for the name of the chord. The root note is the first note you play, and the note upon which the rest of the chord is built. All the other notes in a chord are typically named in relation to the root note. For example, a seventh chord is named because the last note in the chord is the seventh note away from the root note.

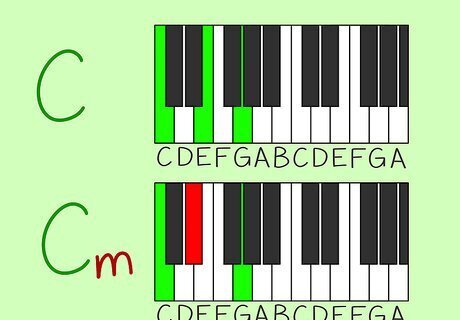

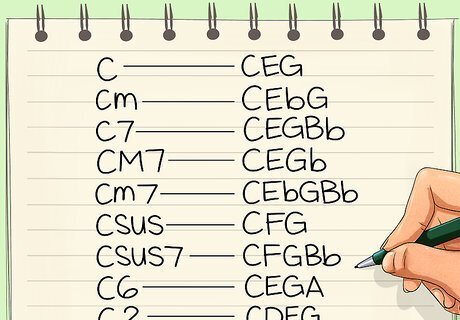

Hear the difference between major and minor chords. Major and minor chords are some of the most basic chords and make up the vast majority of songs you would play on piano. A minor chord is, essentially, a major chord turned upside down. Major chords and minor chords are both three-note chords. Major chords typically are notated simply by the capital letter of the root note. However, seventh chords are the exception to this rule. If you see "C7" on a chord chart, that refers to a C Seventh chord, which is different from a C Major Seventh chord. For seventh chords, you'll see "major" abbreviated either with a "M" or "maj" after the root note. For minor chords, there will be a lower-case "m" after the capital letter. When you play a minor chord, the middle note is lowered by half a step relative to the major chord, but the other two notes remain the same. This gives a minor chord a sadder, more serious tone.

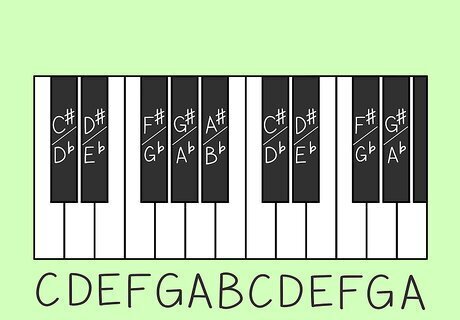

Find sharps and flats. Many keys have sharps or flats in their names, usually represented in the chord name as a "#" for a sharp or a "b" for a flat. These correspond to the black keys on your piano. The black key to the right of, or above, a white key is that key's sharp. For example, the black key immediately to the right of C is C sharp. The black key immediately to the left of, or below, a white key, on the other hand, is that key's flat. Black keys are both to the right and to the left of different white keys. So the same black key that could be considered C sharp could also be considered D flat. Keep this in mind when you're trying to find notes on the piano keyboard.

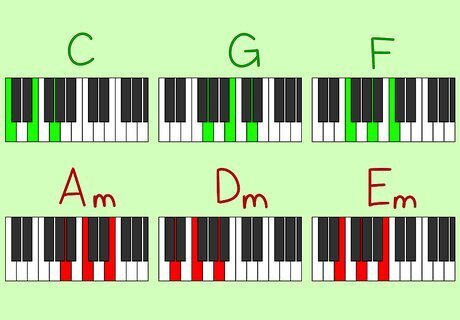

Start with simple chords. There are 6 basic chords that can be played on piano using only the white keys – 3 major chords and 3 minor chords. You can play songs using these chords without having to worry about sharps and flats. The three major chords are C, G, and F. The three minor chords are A minor, D minor, and E minor. These chords are a good place to start if you're new to piano.

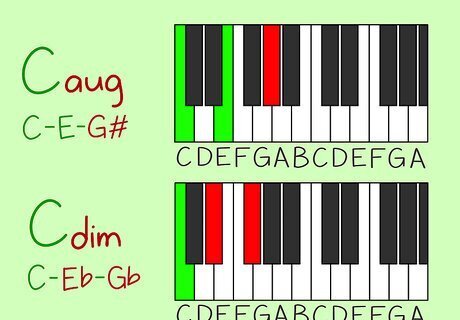

Read the next part of the notation to build the chord. Following the root note and whether the chord is major or minor, the name of the chord will list other information you'll need to play the chord on the piano. Different types of chords are built in different ways. To understand this from the name of the chord, you'll need to learn a little vocabulary. For example, if you see "Caug" on a chord chart, you need to play an augmented C chord. When you augment a chord, you take the major chord and raise the last note a half step. Since a C Major chord would be C-E-G, and a "Caug" chord would be C-E-G sharp. A diminished chord is created in nearly the opposite way, by lowering the middle and last notes a half step. For example, if you saw the name "Cdim" on a chord chart, you would play C-E flat-G flat. You can also think of Cdim as a minor C chord with the fifth lowered by half a step.

Memorize common chords. Check the chord charts for some of your favorite songs to see what chords show up the most often. Write them down and memorize the notes that you play. Whenever you see that notation, you'll know what chord to play without having to get bogged down in music theory. Search online for fingering charts that will show you where to place your fingers for certain chords. You can identify "chord shapes" that will remain the same no matter what the root note. You must place your first finger on the key that corresponds to the root note.

Learning Scales

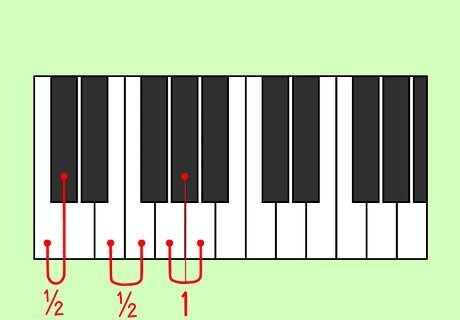

Identify whole and half steps. If you look at the keyboard on a piano, you'll see white keys with black keys between them. Black keys are grouped in pairs and in groups of 3 with a space between. The pattern repeats up and down the entire keyboard. The distance between a white key and the black key right next to it is a half step. The distance between 2 white keys that have a black key between them is a whole step. Practice making whole and half steps up and down the keyboard to get a hands-on understanding of how they work and how the notes relate to one another.

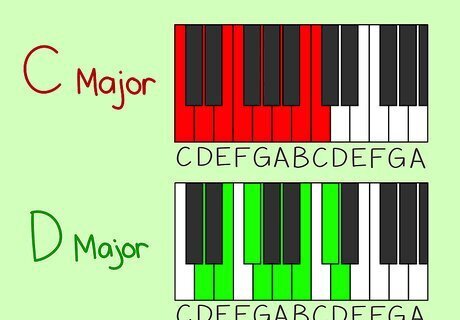

Play the scale for different keys. The scale for a key starts at the root note for that key. All scales follow the "whole-whole-half whole-whole-whole-half" pattern. Once you find the root note, you can play the entire scale by following that pattern. You can find the scales on your own without worrying about any sheet music. Start with C and play each white key until you get to the next C on the keyboard. You've just played the C Major scale, which uses only white keys. Move over to the D and follow the same "whole-whole-half whole-whole-whole-half" step pattern to find the D Major scale. By following the same pattern one key over, you now have to use 2 black keys – F sharp and C sharp. You can follow this pattern from any key on the piano to get the scale for that note. Once your fingers get used to playing the pattern, you may find that you can play a scale without even looking at the keys.

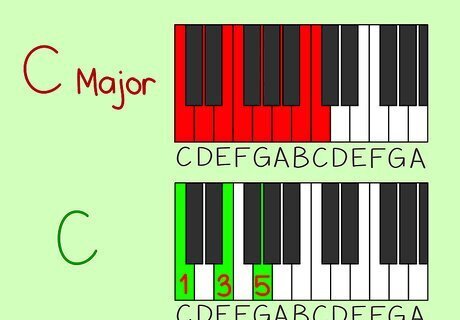

Look for chords within the scale. Once you know the scale, you can find all the major chords by stacking notes in relation to the root note. Form a chord by playing 3 or 4 notes of the scale, starting with the root note. The major chord is the main chord formed by the first, third, and fifth notes in the root note's scale. For example, since the first 5 notes of the C scale are C-D-E-F-G, the C Major chord is C-E-G. To make a minor chord, the third note is lowered by a half-step. For example, C minor would be C-E flat-G. If you play the major chord followed by the minor chord for the same root note, you can hear the difference between the 2 types of chords.

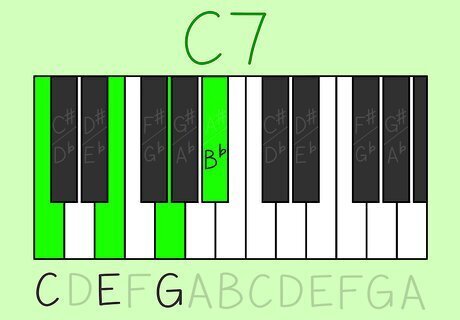

Compare chord names to notes of the scale. Once you know the scale, you can figure out how to play the chord by looking at the name of the chord. The chord name tells you how that particular chord differs from the major chord. For example, with a seventh chord, you play 4 notes instead of 3; the fourth being the seventh note in the scale lowered a half-step. So if you see "C7," you know to play C-E-G-B flat.

Understanding Chord Theory

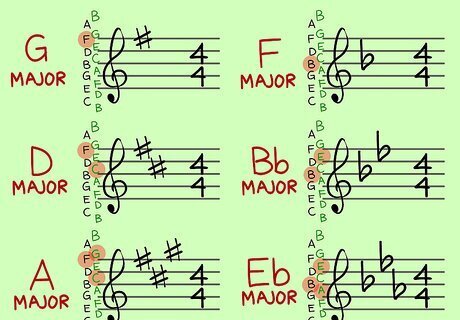

Find the key signature. The symbols at the beginning of the staff lines on a piece of sheet music show you how to play the song. Following the clef symbol to identify the treble or bass clef, you'll see the key signature and time signature. The key signature indicates the key in which the song is played. If it's a key signature other than C major, it will contain sharps or flats somewhere. Those sharps or flats are noted at the beginning of the piece of music. The key signature means that every time you play that note throughout the piece, you'll play the sharp or flat indicated rather than the non-accidental note. For example, the G Major scale includes an F sharp, so for the G Major key signature you'd see a sharp sign (#) over the staff line that represents the F note.

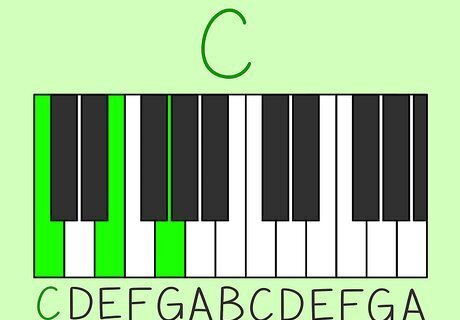

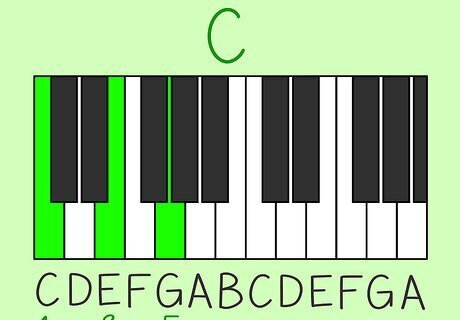

Build a major chord. A major chord is the simplest type of chord you can play. It's a 3-note chord made up of the first, third, and fifth notes on the scale of the root note. Other chords involve making a change to the major chord. You can start with a C major chord, since it's perhaps the easiest. Find the C key on your piano, then skip a white key and place another finger on the third key. Skip another white key and place a third finger on the fifth key. Play these 3 notes at the same time and you have a C Major chord. Applying the same theory, keep your hand in the same position but slide over one key to the D key on the piano. Notice where your fingers now fall. They should be positioned over the D, the F sharp, and the A. If you play these 3 notes together, you're playing a D Major chord.

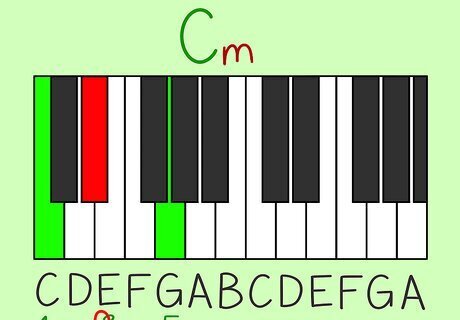

Build a minor chord. A minor chord is played the same as a major chord, except that instead of playing the middle note, or third note of the scale, you play the key to its immediate left, or one half-step lower. All minor chords are built the same way. For example, for a C Major chord, you would play C, E, G, but for C minor you would play C, E-flat, G. You can follow this theory to form all the minor chords the same way you formed all the major chords.

Apply chord theory to seventh chords. Seventh chords get their name from the fact that you're playing 4 notes in the chord, with the fourth note being the seventh note in the root note's scale. For the major seventh chord, you simply play the first, third, fifth, and seventh notes of the major scale. For C Major Seventh, for example, notated as "CM7" or "Cmaj7," you would play C-E-G-B. For any seventh chord that isn't a major seventh, you want to lower the seventh note a half-step. For example, C7 would be C-E-G-B flat. C minor 7, abbreviated "Cm7," is a C-minor chord plus the lowered seventh note: C-E flat-G-B flat.

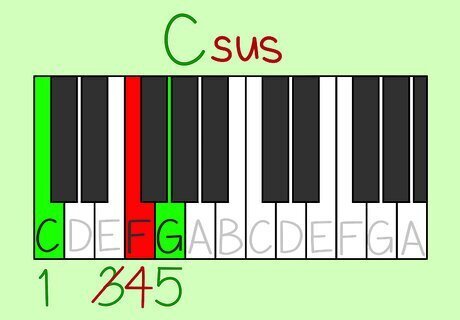

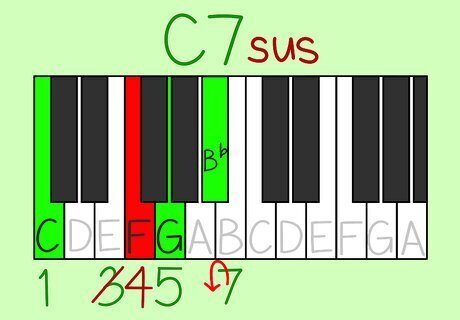

Move on to suspended chords. A suspended chord has an unfinished sound, because you replace the third note of the major scale with the fourth note. To remember this, think of suspending your finger over the third note and dropping it further over on the fourth. Ultimately, you're playing a regular major chord, except instead of playing the first, third, and fifth notes of the scale, you're playing the first, fourth, and fifth notes. Suspended chords may be represented on chord charts with the abbreviation "sus" (short for "suspended") or with the number 4 following the root note (to indicate you play the major chord with the fourth note instead of the third).

Use chord theory to make sense of more complex chords. Once you understand the theory behind the different chords and how they relate to the major chords, you can combine different variations to create more complex chords. For example, you can create a suspended seventh chord by combining a suspended chord with a seventh chord. Play the fourth note of the major scale instead of the third, and then play the lowered seventh note. All 4 notes played together will be a suspended seventh chord. While these complex chords are used rarely in popular music, if you understand chord theory you'll have no problem playing them when you see them on chord charts or in sheet music.

Comments

0 comment