views

Peel off the skin of the cassava tubers.

Use a vegetable grater or peel the skin off with your fingers. Work slowly and carefully so you don’t peel too deep into the root itself. You only want to remove the skin! Traditionally, cassava root is hand-peeled, but you can certainly use a vegetable peeler if you prefer. A sharp paring knife will also do the trick.

Chop the root into smaller pieces.

Cut off and discard the ends with a sharp knife. Then, cut the root into smaller pieces. The actual size of the pieces doesn’t matter too much; 2 in (5.1 cm) pieces will be fine. Cutting the root into smaller pieces makes it easier to grind.

Wash the peeled tubers with water.

Rinse thoroughly since the skin sheds a lot of dirt during peeling. Rinse off the pieces multiple times with cool water until they’re completely clean. Place them on a clean towel.

Grind the pieces with a cassava mill.

The mill reduces the cassava root to a watery, pulpy mash. Use a mobile or stationery cassava grating mill for this. These machines are motorized, so just load the root pieces in, turn on the machine, and use the steering wheel to guide the tubers into the hopper. If you don’t have access to a motorized grater, use a manual cassava grater or rasper instead.

Pack the pulp in baskets and wait 1-2 days.

Store the pulp at room temperature so it ferments properly. Use baskets made of cane, bark, or palm branches. Give the pulp 24-48 hours to complete the fermentation process. Fermentation is crucial for breaking down the cyanide compounds in cassava root. If the cyanide isn't broken down, your batch of flour could be lethal. Proper fermentation is very efficient at this job, though, so try not to worry!

Transfer the pulp into porous bags.

Special porous bags called hessian sacks are traditionally used. Scoop the watery pulp into the porous bags (often called “hessian sacks”) and close up the ends. You may be able to use any porous cloth bag or cheesecloth you have on hand for this. Polypropylene sacks can also be used for this purpose.

Put the bags under heavy weights for 1-2 days.

This removes most of the moisture from your pulp. Whatever heavy items you have on hand should work fine to weigh down the bags. Traditionally, large rocks or logs were used. The pressure of the weight will force the liquids out of the pulp. If you have a manual screw press, use that to "de-water" the pulp a lot faster. If the pulp still looks a bit watery after 2 days, give it 1 more day to finish the process.

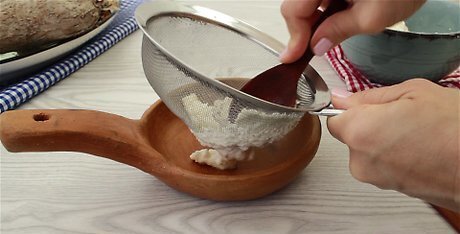

Press the pulp through a wide sieve.

Pressing separates the powder and removes fibers and lumps. The fine cassava powder is the part you need for flour. Go ahead and discard the lumps and fibers that can’t be used in flour. Traditionally, the powder was pressed through a sieve made of palm branches.

Fry the powder in a pan until it’s very dry.

Working in small batches is more efficient and thorough. Transfer the powder to a shallow frying or cast iron pan and heat it up over high heat. Stir the powder constantly to prevent burning. Remove the pan from the heat once the powder is completely dry and brittle. This usually takes 20-30 minutes. Heating the flour gets rid of any remaining cyanide gas, so it's really important! It also kills enzymes and microorganisms in the flour.

Grind the garri and store it in an airtight container.

Let the flour cool to room temperature after you fry it. Then, use a good processor or grinder to grind the flour into a fine or coarse meal. Commercial grade garri is usually sold as extra fine, fine, coarse, or extra coarse. Pack the ground garri in an airtight container and store it in a cool, dry place (a pantry or cabinet should work great). As long as garri is properly stored, it stays fresh for 6 months.

Comments

0 comment