views

X

Trustworthy Source

World Health Organization

Health information and news provided by the World Health Organization

Go to source

It was once very common in the United States, but measles is rare now due to vaccination. In other parts of the world, measles is more common and can be serious and fatal for young children with weakened immune systems, particularly those under the age of five. Researchers say that identifying the most common sign and symptoms of measles in your child and seeking medical care can reduce the risks of serious health consequences.[2]

X

Trustworthy Source

World Health Organization

Health information and news provided by the World Health Organization

Go to source

Recognizing the Main Signs and Symptoms

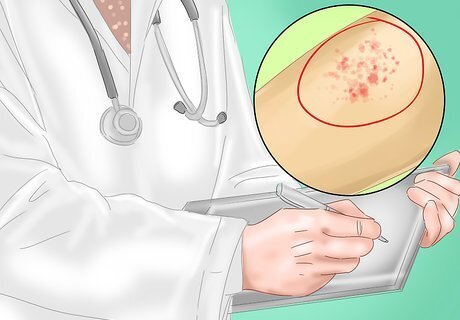

Watch for a distinctive red rash. The most identifiable sign of the measles is the rash it causes, which shows up a few days after the coughing, sore throat and running nose appear. The rash consists of many small red spots and bumps in tight clusters, some of which are slightly raised, but mostly it looks like large flat blotches from a distance. The head / face are the first to break out, with the rash showing up behind the ears and close to the hairline. Over the next couple of days, the rash spreads to the neck, arms and torso, then down the legs to the feet. The rash isn't itchy for most people, but can irritate those with sensitive skin. People with measles typically feel the most ill on the first or second day after the rash develops, and then it takes about a week to fade completely away. Shortly after the rash appears, fever usually rises sharply and can reach or exceed 104 F. Medical attention may be necessary at this stage. Many people with measles also develop small grayish-white spots in their mouth (inner cheeks), which are called Koplik's spots.

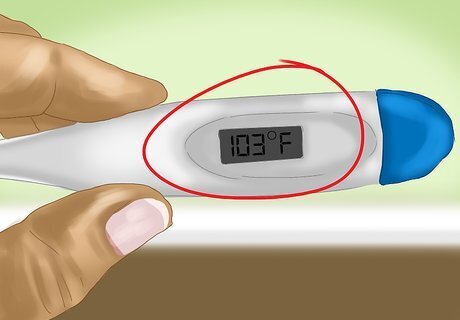

Check for a fever. Measles typically begins with nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as malaise (tiredness) and a mild-to-moderate fever. Thus, if your child seems listless with a poor appetite and has a mild temperature, then chances are good they have a viral infection. However, most viral infections begin the same way, so a mild fever is not a strong identifier for measles by itself. Normal body temperature is 98.6 F, so a fever for a child is any temperature over 100.4 F. A temperature greater than 104 F in children warrants medical attention. A digital ear thermometer, also called a tympanic thermometer, is a quick and easy way to measure a child's temperature. Measles has an incubation period of 10 to 14 days post infection, which is a period of no signs or symptoms.

Look out for coughing, sore throat and a runny nose. Just after you notice a mild-to-moderate fever in your child, then other symptoms quickly develop with measles. A persistent cough, sore throat, runny nose and inflamed eyes (conjunctivitis) are typical of the early stages of the measles. This relatively mild collection of symptoms may last two or three days after the onset of the fever. These signs still don't clearly identify your child's illness as measles — other viral infections, such as the common cold and flu, cause very similar symptoms. The cause of measles is the paramyxovirus, which is highly contagious. It spreads through droplets in the air or on surfaces, then replicates in the nose and throat of an infected person. You can contract paramyxovirus by putting your fingers in your mouth / nose or by rubbing your eyes after touching any infected surface. Getting coughed or sneezed on by an infected person can spread the measles also. A person infected with measles can spread the virus to other people for a period of about eight days — starting when symptoms begin and lasting until the fourth day of the rash (see below).

Recognize who's at high risk. While people who receive the complete vaccine series for measles have almost no risk of getting the disease, certain groups of people are at higher risk for measles. The most at risk are people who: don't get the entire measles vaccine series, have a vitamin A deficiency and/or travel to places where measles are common (Africa and parts of Asia, for examples). Other groups more susceptible to measles are those with weakened immune systems and children younger than 12 months old (because they are too young to be eligible to receive the vaccine). The measles vaccine is usually combined with others that protect from the mumps and rubella. All combined, the vaccine is known as the MMR vaccine. People who get immunoglobulin treatment and the MMR vaccine at the same time are also at higher risk of developing the measles. Vitamin A has antiviral properties and is very important for the health of mucus membranes, which line the nose, mouth and eyes. If your diet is deficient in vitamin, you're more likely to get the measles and experience more severe symptoms.

Getting Medical Attention

Make an appointment with your family doctor. If you notice any of the above-mentioned symptoms in your child or yourself, make an appointment with your family physician or pediatrician for consultation and an examination. Measles in American children has been rare for well over a decade, so doctors who are recently graduated may not have much experience with the distinctive rash. However, all experienced doctors will immediately recognize the characteristic splotchy skin rash, and especially Koplik's spots on the inner lining of the cheek (if applicable). If in doubt, a blood test can confirm whether the rash is actually measles. The medical lab will look for the presence of IgM antibodies in your blood, which are produced by your body to fight against the measles virus. In addition, a viral culture can be grown and examined from secretions swabbed from your nasal passages, throat and/or inner cheeks — if you have Koplik's spots.

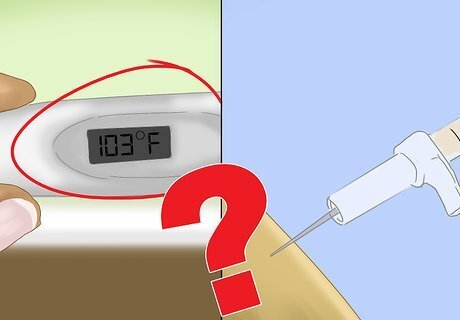

Get the appropriate treatment. There's no specific treatment that can get rid of an established case of measles, but some measures can be taken to reduce the severity of symptoms. Non-immunized people (including children) can be given the MMR vaccine within 72 hours of exposure to the paramyxovirus and it may prevent symptoms from developing. However, as noted above, it often takes 10 days of an incubation period before the mild symptoms of measles begin, so catching it within 72 hours is unlikely unless you're traveling to an area where many people obviously have the disease. Immune boosting is available for pregnant people, young children and people with weakened immunity who are exposed to the measles (and other viruses). Treatment involves an injection of antibodies called immune serum globulin, which ideally should be given within 6 days of exposure in order to prevent the symptoms from becoming severe. Immune serum globulin and the MMR vaccine should not be taken at the same time. Medications for reducing aches and pains, and the moderate-to-severe fever that accompanies the rash of measles include: acetaminophen (Tylenol), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve). Never give aspirin to children or teenagers with the measles to control fever. Aspirin is approved for use in kids older than 3 years, but it can lead to Reye's syndrome (potentially life-threatening condition) in those with chickenpox or flu-like symptoms — which can be confused with the measles. Give children acetaminophen (Tylenol), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) or naproxen (Aleve) instead.

Avoid complications from the measles. Although potentially deadly (especially in developing countries), cases of the measles are rarely serious, nor require medical attention unless fevers get above 104 F. However, the potential complications from the measles are often much worse than the initial viral infection. Common complications stemming from the measles include: bacterial ear infections, bronchitis, laryngitis, pneumonia (viral and bacterial), encephalitis (brain swelling), pregnancy problems and reduced blood clotting ability. If you are experiencing other symptoms after having measles or if you feel like your symptoms never went away, you should see your doctor. If you have low levels of vitamin A, ask your doctor for a shot in order to reduce the seriousness of the measles and any potential complications. Medical dosages are usually 200,000 international units (IU) for two days.

Comments

0 comment