views

Planning a Well

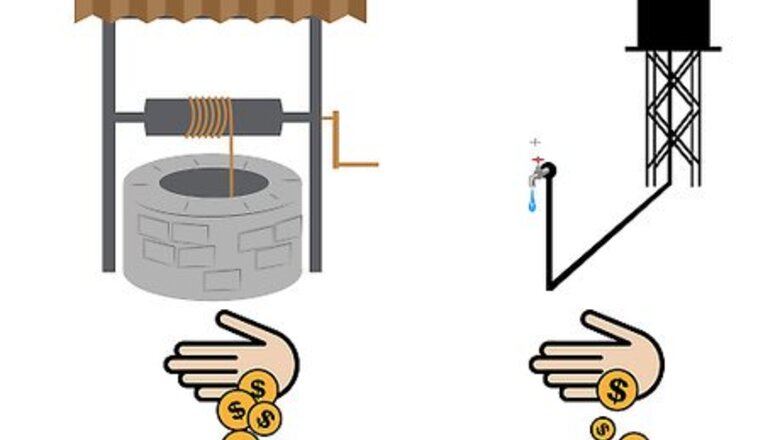

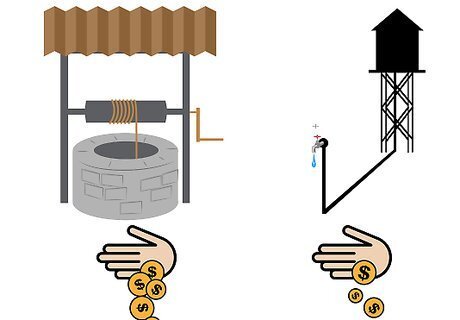

Consider the costs and benefits of drilling a well against piping or shipping water in. Drilling a well involves a higher initial cost than connecting to a public water supply, as well as risks of not finding enough water or water of sufficient quality and ongoing costs to pump the water and maintain the well. However, some water districts may make residents wait years before they can be connected to a public supply, thus making well drilling a viable option where there is enough groundwater at a reasonable depth.

Know the specific location of the property where the well is to be drilled. You'll need to know the section, township, range and quarters to access land and well records through your state's geological survey or from your State Watermaster.

Find out what previous wells have been drilled on the property. Geological survey records or state well drilling reports will record the depths of previous wells in the area and whether or not they found water. You can access these records in person, by telephone or online. These records can help you determine the depth of the water table, as well as the location of any confined aquifers. Most aquifers are at the depth of the water table; these are called unconfined aquifers, as all the material above them is porous. Confined aquifers are covered by nonporous layers, which, although they push the static water level above the top of the aquifer, are more difficult to drill into.Drill a Well Step 3Bullet1.jpg

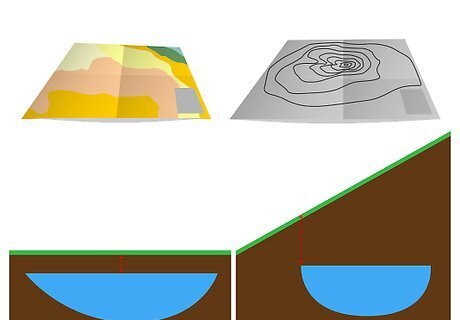

Consult geologic and topographic maps. Although less useful than well-drilling records, geologic maps can show the general location of aquifers, as well as the rock formations in an area. Topographic maps show the surface features and their elevations and can be used to plot well locations. Together, they can determine whether an area has sufficient groundwater to make drilling a well viable. Water tables are not uniformly level, but follow ground contours to some extent. The water table is nearer the surface in valleys, particularly those formed by rivers or creeks, and is harder to access at higher elevations.

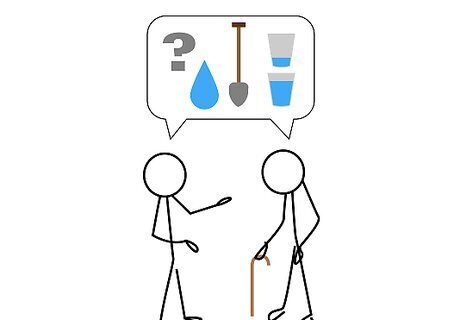

Ask people who live near the property. Many older wells have no documentation, and even if records exist, someone who lived nearby may remember how much water those wells produced.

Get assistance from a consultant. Your state's geological survey personnel may be able to answer general questions and direct you to resources beyond those mentioned here. If you need more detailed information than what they can provide, you may need the services of a professional hydrologist. Contact local well drilling companies, especially ones that have been established for a long time. A 'Dowser' or 'Water Witcher' is a person who uses willow branches, brass rods or similar items to search for water. If you want, you might employ one to help you find a good site.

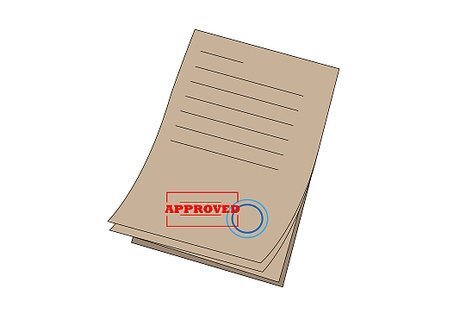

Get whatever well-drilling permits you need. Consult the appropriate municipal and state agencies to find out what permits you need to obtain before drilling and any regulations that govern drilling wells.

Drilling the Well

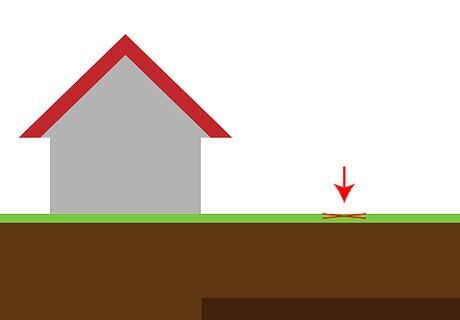

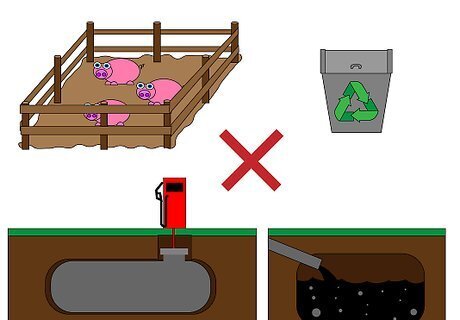

Drill the well away from any potential contaminants. Animal feedlots, buried fuel tanks, waste disposal and septic systems can all pollute groundwater. Wells should be drilled in places where they can easily be reached for maintenance, and located at least 5 feet (1.5 meters) from building sites. Every states has regulations regarding where wells can be located as well as setbacks that you must follow. The well driller should be very familiar with these.

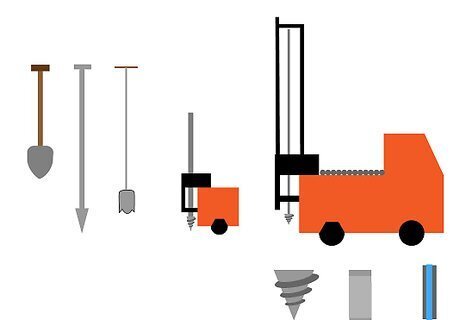

Decide how you want to drill the well. Most wells are drilled out, but wells may also be dug or driven, if conditions warrant. Drilled wells may be bored with an auger or rotary tool, smashed out with a percussion cable or cut with high-pressure jets of water. Wells are dug when there is sufficient water near the surface and no intervening dense rock. After a hole is made with shovels or power equipment, a casing is lowered into the aquifer, and the well is then sealed against contamination. Wells no deeper than 20 feet (6.1 m) are usually classified as 'Ground Water.' As they are shallower than driven or drilled wells, they are more likely to go dry when drought lowers the water table. They are often contaminated with chloroform or E. Coli bacteria, so it is important to have them tested regularly.Drill a Well Step 9Bullet1.jpg Wells are driven by attaching a steel driving point to a stiff screen or perforated pipe, which is connected to solid pipe. An initial hole wider than the pipe is dug, then the assembly is pounded into the ground, with occasional turnings to keep the connections tight, until the point penetrates the aquifer. Wells can be hand-driven to depths of 30 feet (9 meters) and power-driven to depths of 50 feet (15 meters). Because the pipe used is of small diameter (1.25 to 12 inches, or 3 to 30 centimeters), multiple wells are often driven to provide sufficient water.Drill a Well Step 9Bullet2.jpg Augers can be either rotating buckets or continuous stems and can be turned either by hand or with power equipment. They work best in soils with enough clay to support the auger and don't work well in sandy soil or dense rock. Auger-bored wells can be drilled to depths of 15 to 20 feet (4.5 to 6 meters) by hand and up to 125 feet (37.5 meters) with power augers, with diameters ranging from 2 to 30 inches (5 to 75 centimeters).Drill a Well Step 9Bullet3.jpg Rotary drills exude water based drilling fluid such as a bentonite clay slurry to keep the hole open. They may use an additive to reduce heat, clean the bit, and remove debris. The high-pressure compressed air in a rotating bit make drilling easier while pumping out the drill cuttings. Typically the driller will use an oversized dual or tri-cone roller bit to drill down through softer strata until it reaches a solid strata formation. A smaller steel well casing is inserted at this point. These can drill to depths of 1000 feet (300 meters) or more, creating holes from 3 to 24 inches (7.5 to 30 centimeters) wide. While they can drill faster than other drills through most materials, they have trouble drilling through rock in boulder formations. While the drilling fluid makes it tough to identify material from water-bearing strata, the drill operator can use water and air to flush the well and determine whether or not the aquifer has been reached.Drill a Well Step 9Bullet4.jpg Percussion cables work like pile drivers, with bit or tool moving up and down on a cable to pulverize the ground being drilled into. As with rotary cable drills, water is used to loosen and remove intervening materials, but it does not flow from the drill bit. Rather, it is added from the top manually. After a while, the cutting tool is replaced by a 'Bailing' tool. Percussion cables can drill to the same depths as rotary drills, albeit much more slowly and at higher cost, but they can smash through materials that would slow rotary bits. Often when drilling in more solid rock formations, a cable tool rig may be more efficient in finding small fissures of water than a rotary air machine as the rotary air drill seals off such fissures with high air pressure.Drill a Well Step 9Bullet5.jpg High-pressure water jets use the same equipment as rotary drills, without the bit, as the water both cuts the hole and lifts out drilled material. This method takes only minutes, but jet-drilled wells can be no more than 50 feet (15 meters) deep, and the drilling water needs to be treated to prevent it from contaminating the aquifer when the water table is penetrated.Drill a Well Step 9Bullet6.jpg

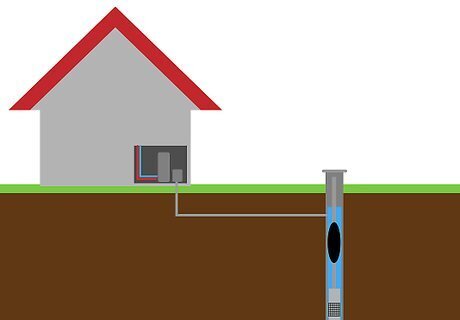

Finish the well. Once the well is drilled, casing is inserted to prevent the water from wearing away and being contaminated by the sides of the well. This casing is usually narrower in diameter than the well hole itself. The most common type for domestic installations is 6 inches (15 cm) in size. They are frequently made out of steel or Schedule 40 PVC. They can be sealed in place with a grouting material, commonly either clay or concrete. To prevent ground water contamination, a bag to filter out sand and gravel is inserted in the casing, then the well is capped with a sanitary seal. Unless it is an Artesian Well and the water is already under pressure, a pump is attached to bring the water to the surface. Sometimes for the steel casing, a perforator tool is inserted and slowly pulled up to determine the the depth of the water. Using the drill's compressed air at low volume, it drives a wedge out into the casing multiple times, cutting an opening for water to flow into the casing. In sandy soils, a solid piece of casing 5–10 feet (1.5–3.0 m) in length may be used. These have a steel laser-cut slotted screen in a 10 feet (3.0 m) section welded to the top of the casing or a solid casing welded to top of a slotted screen. For extremely sandy soils, a 4 inch PVC pipe and screen is inserted inside the steel casing. Small 'pea' gravel is slowly poured outside of PVC liner casing but inside of the steel casing. This improves the filtration of sand.

Comments

0 comment