views

Using Different Types of Rhythm

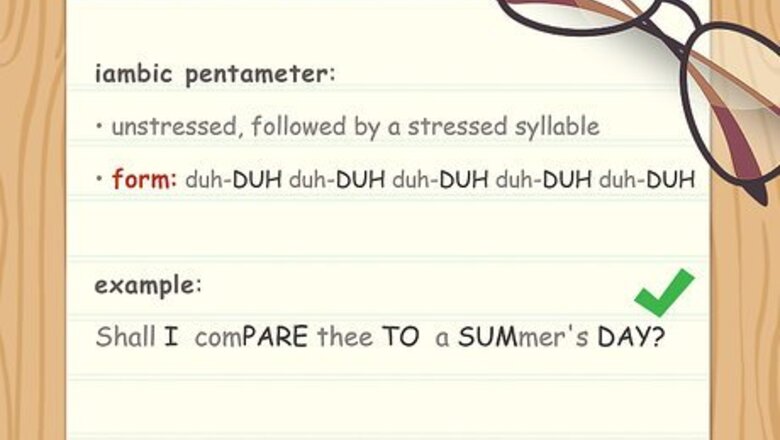

Choose a simple pattern of unstressed/stressed. When a line of poetry uses a pattern of unstressed/stressed, it is known as an iamb. This is the most common form of rhythm in poetry, so you will notice it often. You can easily integrate this type of rhythm into your writing by ensuring that your syllables are arranged in the same pattern. Listen for stressed syllables after ones that have a softer sound. They will sound like “duh-DUH.” For example, “What LIGHT from YON • der Window breaks?” includes an iambic pattern.

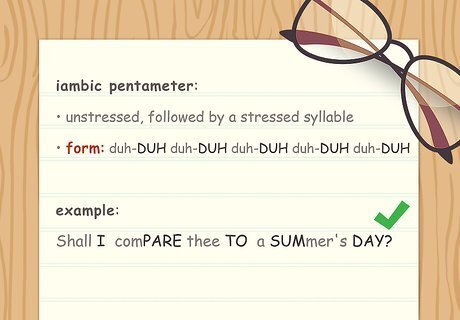

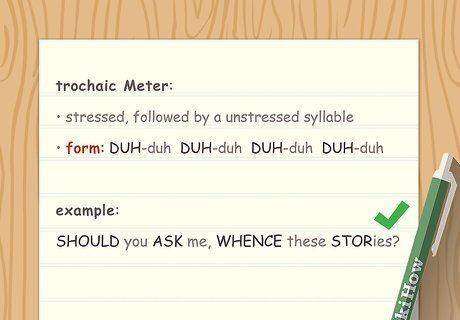

Try following stressed syllables with unstressed syllables. A trochee is just the opposite of an iamb. The stressed syllables come before the unstressed ones. Listen for stressed syllables at the beginning of words when you read them out loud. The words will sound like “DUH-duh.” For example, “TYger! TYger! BURN • ing bright,” features a trochaic pattern.

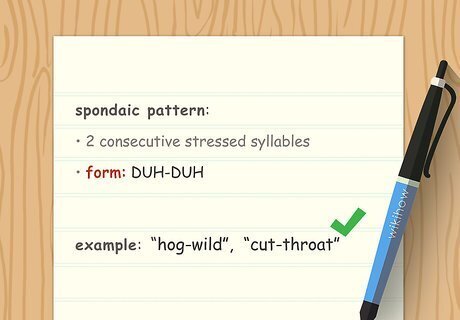

Use 2 consecutive stressed syllables. If you notice 2 syllables in a row that are stressed in your poetry, then you might have a spondaic line. Some words even feature a spondaic pattern, such as “hog-wild” and “cut-throat.” Instead of a soft syllables coupled with a louder one, spondees sound like 2 loud bursts, such as “DUH-DUH.”

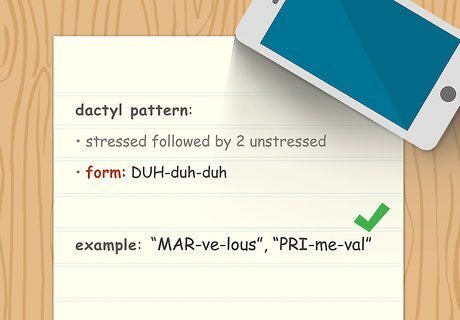

Opt for a stressed syllable followed by 2 unstressed syllables. A slightly more complex way to incorporate rhythm is a dactyl. You can create a dactyl by starting with a syllable that is stressed, and following it with 2 unstressed syllables. The words “poetry” and “basketball” are examples of dactyls. This type of rhythm would sound like, “DUH-duh-duh.”

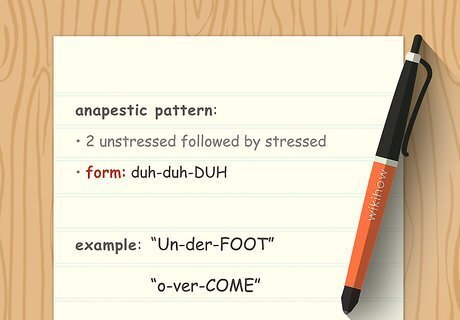

Include 2 unstressed syllables followed by a stressed syllable. Anapests are the opposite of dactyls with the 2 unstressed syllables coming first and the stressed one after them. “Underfoot” and “overcome” are examples of anapestic words. The sound you are looking for is, “duh-duh-DUH.”

Adjusting the Rhythm of Your Poem

Read your poem out loud. You can often hear the rhythm in a poem when you read it out loud—your readers will even hear it in their heads when they read your poem. Try reading what you have written so far and listen carefully. You may even want to record yourself reading your poem and then play it back. Reading out loud will also help you to identify the stressed and unstressed syllables in your poetry, which are crucial for creating rhythm. Some questions to consider when you read aloud include: Does the poem have a noticeable beat when you read it out loud? If so, what is it? Is there a musical quality to the poem? If so, what tune might go well with the poem? What syllables or words have the most and least emphasis when I read them out loud?

Identify stressed and unstressed syllables in words. The main difference between syllables in words that are stressed and unstressed is how long it takes you to say the syllable. Patterns of these long and short syllables in poetry is what creates the rhythm. To adjust the rhythm of your poetry, re-read what you have written and be on the lookout for these different types of syllables. For example, in the word “today” the unstressed syllable is at the beginning of the word and the stressed syllable is at the end of the word, so the emphasis is on “day” and it sounds like “to • DAY.”

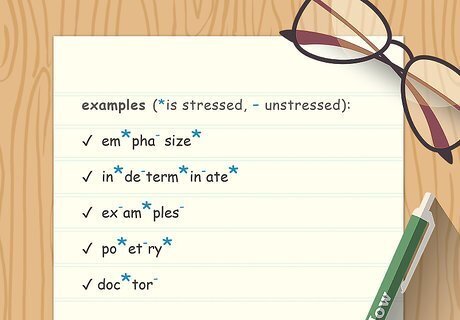

Mark the syllables to indicate if they are stressed or unstressed. Placing a special mark above syllables that are stressed and unstressed may help you to adjust your poem and create a stronger rhythm. Make a distinctive mark for each type of syllable and place it above or below the line. For example, you could place an asterisk (*) above syllables that are stressed and a dash (-) above syllables that are unstressed.

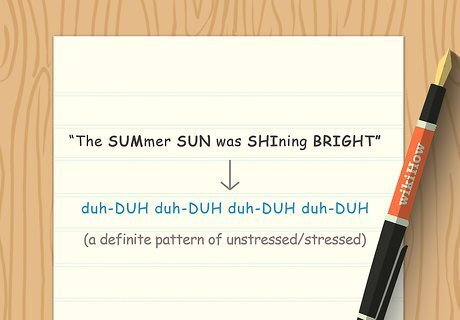

Look for patterns in the syllables. After you have marked your poem to indicate what syllables are stressed and unstressed, go back through the poem and look for patterns. You should notice a pattern easily if your poem has a distinct rhythm. If not, then you can use the lack of a pattern to help you adjust what you have written. For example, a line that reads, “The SUM • mer SUN was SHI • ning BRIGHT,” has a clear syllable pattern of unstressed/stressed/unstressed/stressed. On the other hand, a line that reads, “The SUN was BRIGHT that day,” does not have a distinctive pattern. You could adjust it to something like, “The RIS • ing SUN was BRIGHT that DAY,” so that the syllables have a definite pattern of unstressed/stressed/unstressed/stressed.

Taking Your Poetry to the Next Level

Read poetry for inspiration. The more poetry you read, the more exposure you will have to different ways of incorporating rhythm, and this will help you to develop as a writer. Pick up an anthology of poetry and work your way through it, or get a book of poetry by someone who uses rhythm in a way that you like. Read the poems out loud and listen for the rhythm. Mark the unstressed and stressed syllables in some of the poems to give yourself practice at identifying different forms of rhythm. Attempt to recreate a poem's rhythm using your own writing. For example, you could take the syllable pattern of a poem and use it to help you add the same rhythm to one of your poems.

Join a writing group. Bouncing your ideas off of people who are well-read in poetry and who have a genuine interest in writing poetry can help you to improve your own poetry. Reading in front of an audience of people is also a great way to get feedback on the rhythm of your poems. Check your local library, coffee shop, and community center for a writer's circle that you can join. Bring your poetry with you to the group and let people know that you are hoping to improve the rhythm of your poetry. Try saying something like, “I want to work on creating rhythm in my poems, so any feedback you can provide along those lines would be especially helpful.”

Take a poetry writing class at a local college. If you want some professional help with your poetry, consider signing up for a class at a local community college. Check the schedule to see if there are any poetry writing classes, or even just a creative writing class that you could take. Taking a class will give you an opportunity to learn more about writing poetry in general. As an added bonus, by taking a class you will also be able to get feedback from someone who studies poetry—and possibly even publishes their own poetry—for a living.

Comments

0 comment