views

Handling Social Situations

Remember that autism is a neurological disability, not a disease. It comes with benefits as well as challenges. Autistic people are usually funny, insightful, detail-oriented, and moral. They may need help with social skills, anxiety management, choice making, and understanding unwritten social rules. Since autistic people are very diverse, it's difficult to generalize about their traits. Living well isn't just about learning how to handle your weaknesses. It involves building and capitalizing on your strengths.

Find a social mentor. Talk to someone close to you who you trust about being your social mentor. They could be a friend or a family member, but having the support of your family is ideal. Family education can help you to navigate the different facets of your treatment, such as behavior regulation, language and communication skills, social skills, and teaching. They can help you understand social situations and deal with different scenarios. Not only can your social mentor help you in live situations, they can also role play fictional situations with you so you can practice and learn what to do in situations you've not yet encountered. Even though you may be more communicative and social than many people on the spectrum, you still may have difficulty understanding social cues or reading body language correctly. Your social mentor also can help you read situations after the fact. For example, after having a brief conversation with a girl, your social mentor may tell you the girl was flirting with you. Your social mentor then can explain the mannerisms or body language that led them to believe the girl was flirting with you. The person you choose to be your social mentor should be someone who lives near you and is available to attend social functions and events with you. They can not only explain interactions, but also rescue you if you get yourself into a tight spot and don't know what to do. Certain areas of socializing, especially socializing with non-autistic people, may be difficult for you. Therapies such as RDI can help you work on learning how to interact with neurotypicals.

Decide how you feel about socializing. Before you invest time in any extensive effort to understand and better fit in socially, you might want to think about whether it's something you care about and what you hope to get out of socializing if you could do it better. It's often the case that by the time autistic people reach their teenage or adult years, they've decided they don't care anything about socializing. If you think small talk is torture, you may decide there's no real point in learning how to do it well. A lack of social and emotional sensitivity is a hallmark of Asperger’s, so you may need to develop ways of dealing with emotional and social situations. Try to view social encounters in a positive way. For instance, rather than worrying an upcoming event will be difficult or awkward, think about how you'd like the encounter to flow smoothly and comfortably. When you coach your brain to consider ways an experience might go well, it makes it more likely that the situation will be successful. One option is to develop some sort of exit strategy. For example, if someone at a social event starts talking about the weather or asks you about your family, you might say "I'm sorry, I don't do small talk. Maybe we could talk about movies instead?" You can steer the person towards one of your special interests or something else that you find interesting. Depending on your interests and your focus, you may find little use for socializing in your life. For example, computer programming or writing/editing tend to be solitary pursuits. If you'd rather do that and don't care about going to parties, don't force yourself to do something that you don't enjoy. Keep in mind that there are plenty of neurotypical people who also don't enjoy parties and other social events.

Figure out which limitations you can work on, and which ones you need to make peace with. You should only try to improve things that are reasonable, and it's not wise to push yourself to do things that hurt or exhaust you. Work with what you have, and remember that you can define your own success instead of pressuring yourself to do everything that neurotypicals can do. For example, you may be able to learn better listening skills, but you might not be able to erase your need for extra downtime. It would make sense to read articles about listening, but it wouldn't make sense to push yourself to work too hard and risk burnout. You might not be able to do all the things that neurotypical people can do. Certain things, like hosting large parties, pulling all-nighters, or driving in heavy traffic, may not be realistic goals for you (depending on your individual skills and needs). This is okay.

Read etiquette and self-help books. Many neurotypical people seem to understand by instinct or intuition what's expected of them in social interactions. But it turns out the "unwritten rules" aren't really unwritten at all. There are plenty of books that can help you understand and manage social situations. You can check out etiquette books at the library to learn about formal manners and how to act in various formal situations. Even though formal etiquette may be a bit much for casual social situations with your peers, you can't go wrong with being too polite. There also are self-help books available on a variety of social topics, including handling social anxiety, reading body language, and the art of conversation. Study the topics in which you're interested to improve your social skills your way. If you have any questions based on anything you read in an etiquette or self-help book, ask your social mentor or another friend about it. For example, you might say "I read that if you accidentally break something at a party, you should offer to replace it? Is that something people do? Have you ever seen such a thing happen?"

Learn coping skills. Many autistic people have to deal with a lot of stress in life. Find things that make you feel better, such as talking to loved ones, stimming, engaging with special interests, spending time outside, exercising, playing with a pet, or other things that help you feel better. Make time for your mental health each day, and take special care of yourself if you're going through an unusually stressful time. Learn how to handle sensory overload and meltdowns. Set aside a quiet space in your home where you can retreat if you're stressed or overwhelmed. Fill it with comforting things, like soft textures, stim toys, favorite music, and whatever helps you feel at peace. Tell any family members or roommates to leave you be when you're in there. Try to spend time on your special interest(s) each day.

Focus on your strengths. Think about what interests you, and what you're good at. Find ways to embrace, work on, and celebrate these things. Build upon your skills. Being disabled doesn't make you a weak or lesser person—it's just one aspect of who you are. You can still find meaningful work, build worthwhile relationships, and make the world a better place.

Work on your independent living skills. Some autistic people are able to live independently, while others need extra help. Practice daily living skills, so that you have the freedom to live as independently as is possible and reasonable. Start doing laundry, cleaning your room, and doing dishes. Ask your parents for help until you feel able to do it yourself. Find a program that teaches disabled people to drive. Find a job. Job assistance programs are available to help you. Look into supported living, if needed.

Find ways to deal with anxiety. Many autistic people have anxiety disorders, including social anxiety, PTSD, panic disorder, and other types of anxiety. These are treatable, and can be managed (if not cured). Talk to your therapist. Try facing your fears in little pieces. If you're afraid of talking to a guy you like, first smile at him in the hallway. Once you can handle that, try saying "Hi" or "How are you?" Remember that you're in control, and you can back out whenever you start to feel overwhelmed. Ask yourself: what's the worst thing that could happen? Is this realistic? How bad is it likely to get? Is it possible that your thinking is distorted? If you're feeling bad about yourself, take the perspective of a friend. "Would I be okay with my friend being told that she's a loser? Then should I say this to myself?" "Would I judge a friend for slipping up like that?" If not, then don't treat yourself that way.

Cultivate your special interests. They may turn into a fun, secure job someday. Furthermore, your colleagues will share your interests, so you can talk about your passion all the time!

Observe others interacting socially. Autistic people often are praised for their skills at noticing details non-autistic people would overlook. If uncanny observational skills are one of your strengths, put them to use studying people to catalog interactions and experiences. If you decide to observe real people in public, keep in mind that people often don't appreciate being stared at. You might want to bring a book or digital device so you can observe without being noticed. You also can observe people interacting in television shows or on movies. These social interactions are scripted, but they can be helpful in learning how a basic conversation should go. When at a party or other social event, stay at the edge and observe the group until you feel comfortable enough to join. You also can hang out next to a small conversation and listen until you hear someone say something about a topic in which you're interested. Then you can join the conversation without being rude. Just say something like "Excuse me, I couldn't help but overhear that you were talking about a problem with your dog. I volunteer at the local animal shelter and am studying to be a veterinarian – maybe I could offer you some tips."

Create scripts for predictable situations. Your social mentor can help you create scripts that will help you manage basic social interactions that are always pretty much the same, such as buying groceries or going to a restaurant. For example, when you enter a sit-down restaurant, you typically must speak to an employee standing near the door. They often ask for the number of people in your party and your name. The order of these two things typically doesn't matter. You can just say "Hi. Smith, party of four. Thank you." In retail stores, the clerk likely will say hello and ask if you found everything okay. This is a general courtesy question – kind of like when someone says "How are you?" you're expected to answer "Fine, and you?" For a retail clerk, you can simply say "I did, thank you. How are you today?" During a conversation, try talking about whatever the other person is interested in. That way, you don't have to figure out how to initiate the conversation—you can just let the other person take the lead.

Building Interpersonal Skills

Work on reading body language in conversations. There's no perfect rule to know how much you should talk and how much you should listen. The best thing to do is to notice signs of whether someone is interested or disinterested in the conversation. Watch people's body language for clues about what they're thinking about. If someone is interested in what you're saying, they will probably look at you, make sounds like "mm hmm" or "uh huh" from time to time, and give questions or comments. If someone wants to change the subject or end the conversation, they might look away (like at a clock or a door), not talk very much, and look awkward or uncomfortable. If you don't understand someone's body language, you can ask. For example, "I notice you checking the time. Do you need to leave?" or "I have trouble reading body language sometimes. Do you want me to continue?" Sometimes people are interested in monologues, because they want to learn more about your special interests. If they ask, it's okay to dive right in! Monitor their expression, and give pauses to allow them to react, so that you can adjust the subject or answer questions as need be.

Know that you don't need to make eye contact if it makes you uncomfortable. While most neurotypicals like eye contact, it can be distracting or unnerving to autistic people. You don't need to do things that make you uncomfortable. Depending on what you can handle, try one of these: Watch their hands or feet. (Looking in their general direction suggests listening.) Look at their shirt, scarf, or necklace. Observe their chin, mouth, nose, hair, or forehead wrinkles. Look at their left eye briefly and then shift to their right eye. Look at the point between their eyes. Unless they're really close to you, it will appear to them that you are making eye contact.

Ask questions to other people. People love to feel like you're interested in them (and their interests). Ask them questions, and see how they respond. If they don't seem to like one question, you can always ask something else. (For example, maybe they don't like talking about their parents, but they love talking about their dog.) See if you can figure out what they're interested in, and then let them tell you about it. It can be an interesting way to learn more about other people.

Listen with the intent to understand. Try to fully understand how the person feels before you explain your point of view. While this can be a difficult thing to do, people usually respond very well to it, and feel more opening to listen once they know that they're heard. Ask questions to clarify. "She moved the deadline of the report?" Summarize what they've said. "So, you felt frustrated when your dad kept cutting you off like that." (It sounds silly, but it works!) Ask for their opinion. "Did you think it was fair of the academy to do that?"

Ask before offering advice. Many autistic people experience a strong sense of social responsibility, or a desire to help out and fix problems. However, sometimes neurotypicals do not want advice—the best way you can help them is by listening. In this case, it is best to stave off the impulse to help, and allow them to be independent (for better or for worse). "Were you looking for advice, or just someone to commiserate? Because that sounds like it stinks." "Would you like some suggestions on how to deal with that?" "I went through a similar experience last fall. Let me know if you'd like any tips."

Learn when it is appropriate to touch and approach people. Practice what you learned and try to follow the treatment plan recommendations.

Practice validating others' feelings. This practice can cause people to quickly trust and like you. Whether you agree with their actions or not, make it clear that you hear them and sympathize with their troubles. Here are some examples of validating statements: "That sounds difficult. I'm sorry to hear you're going through that." "You sound excited! I'm happy for you!" "Wow, that must have been awkward." "I'm really sorry to hear that. That sounds rough."

Getting Support

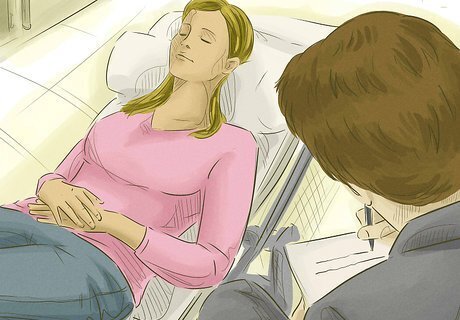

Ask a professional for advice. Consult a psychologist, licensed social worker, occupational therapist, or a psychiatrist to learn more about autism/Asperger's Syndrome. As therapists, they may develop a treatment plan to assist with daily living.

Network with other autistic people online. Autistic people usually use hashtags like #actuallyautistic and #askanautistic. You can share coping strategies, talk about your lives, and make friends who think in ways that you do.

Form a team of people whose judgment you trust: parents, older siblings, relatives, therapists, close friends, et cetera. Whenever you feel uncertain, you can come to them for advice. Hearing a variety of perspectives will help you imagine possibilities so you can make the best decision.

Join clubs or activities related to your special interest. This will give you a chance to make friends who share your passions, and the fun topic will make the outing less exhausting. Even if you don't talk to anyone there, you have a chance to practice something you love. Due to your intense focus and passion, you may even reach a leadership role! This will allow you to coach others (and will look great on your resume).

Search wikiHow for articles on social skills and living. Here are several wikiHow articles that cover living with autism: How to Balance Studying with an Autism Related Obsession How to Avoid Meltdowns How to Explain Autism to People How to Fall Asleep if You're Autistic How to Make Friends if You Have Asperger's Syndrome

Succeeding at School or Work

Focus on your special interests. Children who have Asperger’s can be hyperactive, inattentive, and disorganized, however, many of them also have special interests at which they've become experts. If you have special interests of your own, you have an innate advantage over many other people. You just have to learn how to harness your special interests and steer them towards employment or job skills. For example, if you love animals and have a special connection with them, you might consider a career as a veterinarian. As a vet, your relationship with animals will be far more important than your relationship with people, so your social skills won't be as important. You also have many opportunities to prepare for your career and work with animals by becoming a veterinary assistant or volunteering at an animal shelter. Many other special interests also translate into specific career paths. Even if yours doesn't, you may be able to find something that relates to it in some way, or enables you to use skills similar to those you've developed pursuing your special interest. For example, if autism is one of your special interests, you might consider working as a tutor for autistic children or becoming a counselor who specializes in helping people on the spectrum.

Consider technical programs at trade schools. If you have skills in math and science, as many autistic people do, you might consider using tech programs to develop job skills. Often you can take these classes even while you're in high school. If you're already out of high school, trade schools still offer an affordable way to get job skills. Many trade programs are less expensive than a four-year degree at a traditional university, and trade schools or community colleges often have resources to help you find employment. Consider getting a catalogue for your local community college or trade school and looking at the programs they offer. If you see something that interests you, see if you can sign up for a single class without formally enrolling as a student. You also might be able to send an email to the instructor of a class and ask if you can sit in on a single class session. Just write something like "Hi, my name is Sally. I'm interested in computers and I'm thinking about getting training to become a certified programmer. Would it be possible for me to sit in on your class Monday night to see if it would be right for me?" You don't have to mention that you have Asperger's Syndrome or that you're autistic.

Look for alternatives to fulfill requirements. If you do go to a four-year college or university, you may be required to take classes in subjects that you don't like or have any motivation to pursue. Likewise, you may find you have to do similar tasks as an adult in the working world. For example, you may be in a career or profession that requires a certain number of hours of volunteer work or continuing education every year. If you leave these requirements to the last minute, you won't have as many options. However, if you start as soon as possible you'll have a better chance of finding a way to fulfill those requirements that you can handle without too much difficulty. When working with school general education requirements, talk to a professor to find out if there are other options available to fulfill those requirements. There may be alternative classes available, or projects you can complete instead of taking the class.

Create your own opportunities. When you're autistic, you may find that neurotypical people are able to advance in ways that don't appeal to you or that you never considered. Rather than using your Asperger's Syndrome as an excuse, come up with your own ways to move forward and succeed on your own merits. For example, you may find interviews difficult. Nonetheless, most employers require you to successfully complete an interview before they will hire you. If you can find a way to get your work in front of someone so that they see what you can do before they meet you, the impression you make personally may not make as much of a difference. If you have trouble talking to or socializing with others, consider sending emails to employers or executives instead. Express your interest in a particular field or position, explain your qualifications, and provide work samples if possible. You also may consider explaining yourself up front and telling people that you are autistic. The risk in doing that is that some people may not react well because they have some misconceptions about what being autistic means.

Secure reasonable accommodations. Both at work and at school, you may have the legal right to accommodations because your autism means you aren't able to do things in the same way, at the same speed, or in the same environment that neurotypical people are. If you need accommodations, you have to be able to speak up and ask for them. This means you must be able to explain your problem to someone who has the authority to do something about it. This could be a teacher or administrator at school, or a supervisor at work. Seek out an ally who is willing to help you if you're uncomfortable seeking accommodations on your own. This could be another teacher, a co-worker, or even a friend. Explain to them the problem you're having, and how it could be improved. For example, suppose you got a job in an office where you work in a cubicle surrounded by other cubicles in a room lit with fluorescent lights. The noise from the other cubicles makes it impossible for you to concentrate, and the lights give you a headache and make it difficult for you to focus. Several times, you've gone into the bathroom and banged your head against the door of the stall in an attempt to make everything stop. Look around the office and see how the situation could be alleviated. Maybe there's a conference room or another area where you could work that doesn't have fluorescent lights. This would help your sensory issues. If the noise problem wasn't improved by moving to another part of the office, maybe noise-canceling headphones would do the trick.

Managing Anxiety and Stress

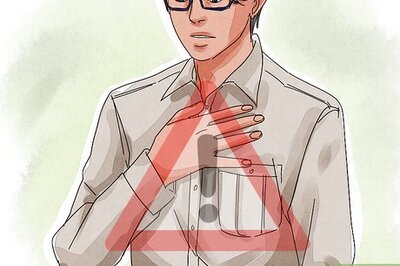

Identify sensory issues. As a child, you may have had a hard time figuring out the specific triggers that set you off. But as you get older, you can start to identify sounds, sights, and other sensations that cause you problems. Once you know where your sensitivities lie and how different environments affect you, find ways to alleviate the problem or avoid it entirely. For example, if you have difficulties in spaces that are lit with fluorescent lights, you might find relief by wearing sunglasses or glasses with colored lenses to blunt the strobing effect. Some situations you can learn to simply avoid. For example, if you're triggered by a certain cologne or perfume, you can stay away from people or places where that smell is prevalent. If you want to adapt your senses so that you're able to handle these situations for longer periods of time, consider going to a psychologist or other mental health professional. You can try therapies designed for people who have phobias, and see if you can gradually adapt so that you're able to endure that particular sensory input for a longer period of time. Treatment for anxiety includes pharmacotherapy along with individual therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and behavior interventions. Accommodations must be made to address sensory sensitivities and educational needs.

Create coping strategies. When a particular sensory issue is so common that avoiding it isn't practical, it may be possible for you to create one – or several – coping strategies that allow you to handle the stress or anxiety produced. For example, if you find it comforting or relaxing to fiddle with something or chew on something, you might consider buying a stim toy that you can carry in your pocket, backpack, or purse so you'll always have it handy. You can buy chewable stim toys that you can wear as a necklace or bracelet if you want something to chew on. Some people also find it helpful to visualize a happy memory or an imagined peaceful place such as a waterfall or a warm beach. Focus your mind on your visualization and connect to it with all of your senses until you feel the tension leaving you. Progressive muscle relaxation also can help reduce stress. Some people find it helpful to use if they feel they are on the verge of a panic attack or meltdown. Identify each of your muscle groups and focus on tensing the muscles in each one for a few seconds, then relaxing them for a few seconds. It can take a few weeks to master this technique, but once you've got it down you may find it helpful. Use any combination of these coping mechanisms when you encounter an uncomfortable or overwhelming situation. If nothing seems to help, try to have an exit strategy in place as well so you can safely remove yourself from the situation if you need to do so.

Practice slow breathing techniques. When you start to panic, your breathing will become short and shallow. You may start to feel your throat tighten, or feel that you can't get your breath. If this happens, concentrate on breathing deeply through your nose, then out through your mouth. Expand your chest and belly as you breathe in, making room for the air. Then depress your chest and belly as you breathe out, as though you are forcefully squeezing the air out. This is called belly breathing and it relaxes you by stimulating your Vagus nerve and parasympathetic nervous system. Mastering deep breathing can not only decrease stress but boost your overall health mentally and physically. Taking a break and focusing on your breath pulls you out of a stressful situation and centers you so that you're ready to deal with the task at hand. Focus your attention on your breath – you also may want to count or repeat a phrase such as "I am calm" or "I am at peace." Try breathing in slowly through your nose for 3 seconds, hold your breath for 5 seconds, and exhale slowly through your mouth for 7 seconds. Repeat this cycle 10 times to help yourself feel more calm. Don't hold your breath. Rather, think of the breath as a circle, coming in and going out in a continuous cycle that never ends.

Try therapy or medication. Many autistic people have problems with depression, or have severe social anxiety. Anti-anxiety or anti-depressant medications may give you some relief from some of these symptoms so you can cope with Asperger's Syndrome and better handle the world at large. Keep in mind that it may take you some time to find the right doctor, and it may take the doctor some time to find a medication that helps you. Depression may be exacerbated by experiences like negative socialism including isolation, marginalization, and bullying. Antidepressant use has an increased potential for suicidal ideation in children and adolescents. Look for a doctor who has experience working with people similar to you. For example, if you are an autistic person who has depression and social anxiety, you want a doctor who has experience treating social anxiety and depression in people who are on the spectrum. For therapy or medication to work, you have to be willing to be open and honest with your doctor about what you're experiencing and the effects of your treatment, if any. If something isn't working, don't be afraid to speak up and tell your doctor that you're not noticing any results. On the other hand, if you find something that works for you, don't be ashamed of taking it. If it improves your quality of life, it's a good thing for you.

Comments

0 comment