views

Aztec Melee Weapons

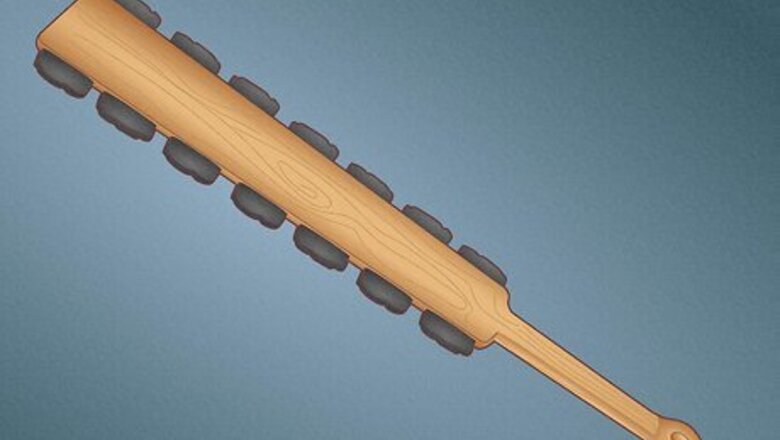

Macuahuitl (obsidian-edged club) Amacuahuitl, or the “obsidian chainsaw” as some call it now, was a broad, flat wooden club studded around the edges with wickedly sharp obsidian blades. While it could definitely kill, its primary purpose was to tear flesh and inflict injury so that enemy soldiers could be captured and brought back to the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, for sacrifice. The macuahuitl is the most well-known Aztec weapon today, and was definitely one of the most feared in the Middle Ages! The macuahuitl was also feared by the Spanish conquistadors when they encountered the Aztecs, although the obsidian blades were often not strong enough to pierce metal European armor.

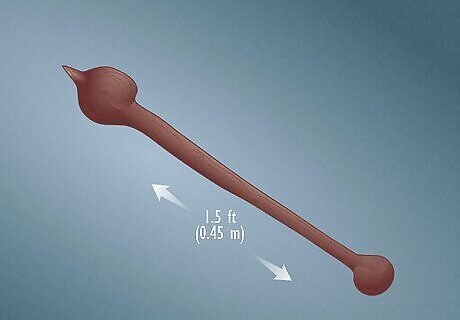

Macuauitzoctli (double-ended club) This club, made of hardwood, was about 1.5 feet (0.45 meters) long with a pointed tip and had knobs on each end. It could be used to beat or club opponents or jab them, and has been likened to the medieval European “morning star” weapon. These clubs were fairly unspecialized and were widespread.

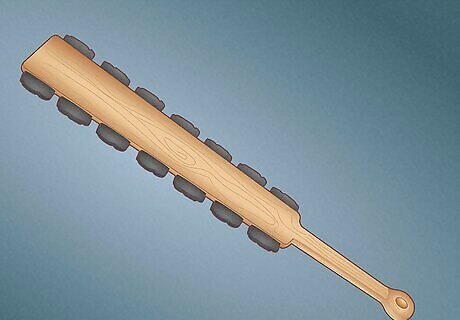

Huitzauhqui (studded bat or club) Meant to represent the god Huitzilopochtli, this club was made of wood and somewhat resembled a modern baseball bat. It could be used to beat or swing at enemies and was sometimes studded with flint or obsidian blades on the sides for extra cutting and slicing power. Spiritually, this weapon was considered an offering to the gods and symbolized the harmony between life and death.

Cuahuitl (wooden baton) Fashioned from one solid piece of hardwood (possibly oak), this baton was used in battle to club and beat opponents, inflicting deadly blunt force trauma. Its shape was somewhat reminiscent of the leaves of the agave plant.

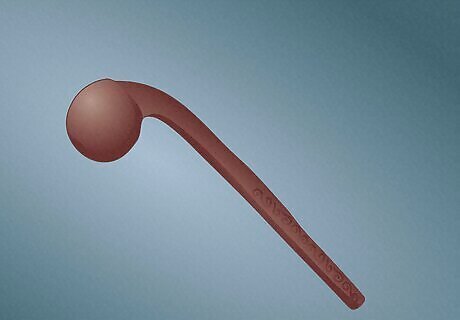

Cuauhololli (wooden mace or club) Thecuauhololli was a mace made of wood with a ball at the end. In battle, it was used to smash and crush opponents and shields. Sometimes, the head would be embedded with sharp stones or blades made of obsidian, like the macuahuitl, to deliver extra damage.

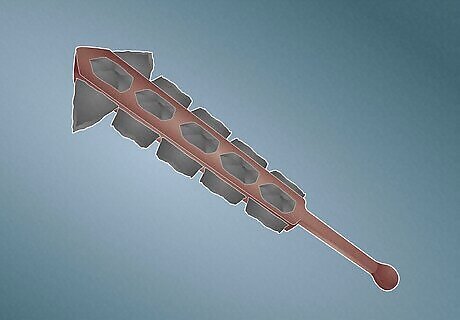

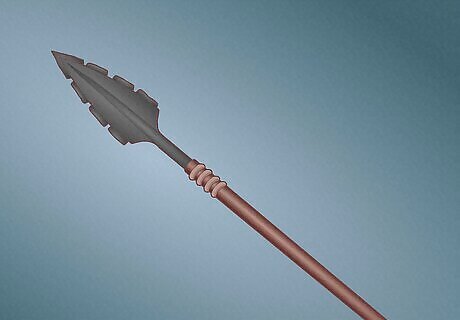

Tepoztopilli (obsidian-tipped spear) Atepoztopilli was a long spear (about the length of a man) with a broad, spade-shaped tip about twice the size of the palm of your hand. The edges of the tip were studded with jagged obsidian blades, and the weapon’s long shaft meant that a less experienced fighter could stand behind elite warriors and poke or jab opponents with it.

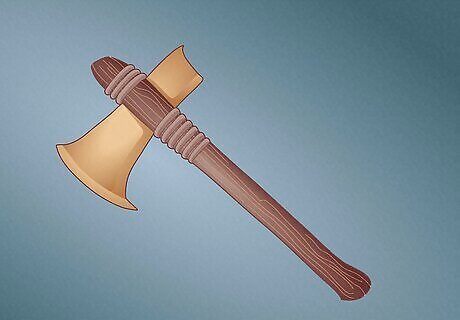

Itztopilli (axe) Axes were not as common as clubs, spears, and other weapons, but are thought to have been used in the late Aztec Empire. The axe blades were made of stone, obsidian, or sometimes copper (although the Aztecs mainly used copper for ceremonial purposes) and were lodged in a long, wooden handle. The tlāximaltepōztli was a special type of axe, similar to a tomahawk, that represented the god Tepoztecatl. The blade had a 2-side design: one side was a sharp blade meant for cutting, while the other side was a blunt protrusion used for clubbing.

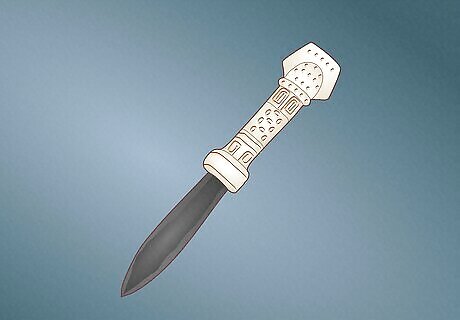

Tecpatl (dagger) Thetecpatl was a ceremonial dagger made from obsidian with a stone or wooden handle that was most often used in ritual sacrifices. It could make a great backup weapon on the battlefield, but wasn’t primarily used to fight. It was most often carried by members of the warrior priest class.

Aztec Ranged Weapons

Atlatl (wooden spear-thrower) Theatlatl was a wooden dart-throwing device that let Aztec warriors launch long darts (mitl) and javelins (tlacochtli) tipped with stone or bone at their opponents from a safe distance. They were most often used in the first stage of battle as the 2 opposing armies faced and began advancing toward each other.

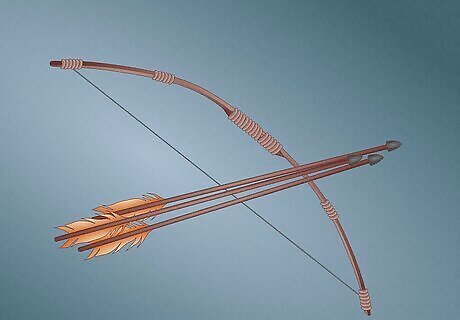

Tlahuitolli and yaomime (bow and arrow) Bows (tlahuitolli) were common in the Aztec army and could be as long as 5 feet (1.5 meters). The deadly arrows (yaomime) were pointed with flint, bone, or obsidian and kept in a quiver called a mixiquipilli. Some experts believe the arrows could fly as far as 450 feet (137 meters) to deliver fatal blows to enemies.

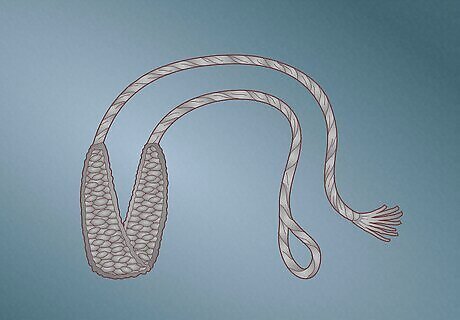

Tematlatl (sling) Aztec battle slings were made from fibers of the maguey plant (agave americana) and used to hurl stones at opponents from up to an estimated 650 feet (198 meters) away. The stones were chosen and shaped ahead of battle and could be slung so accurately and forcefully that they could even deliver damage to metal European armor.

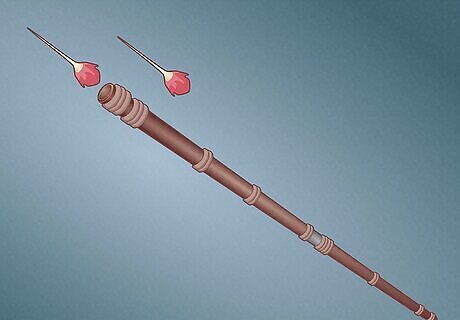

Tlacalhuazcuahuitl (poisoned dart gun) Thetlacalhuazcuahuitl was a blowgun made of a hollow reed and filled with wooden poisoned darts for ammunition. The darts were usually dipped in the neurotoxic secretions from the skin of poisonous tree frogs native to central Mexico. These weapons were most often used for hunting, but could be used in battle as well (particularly stealth attacks and raids).

Aztec Armor and Shields

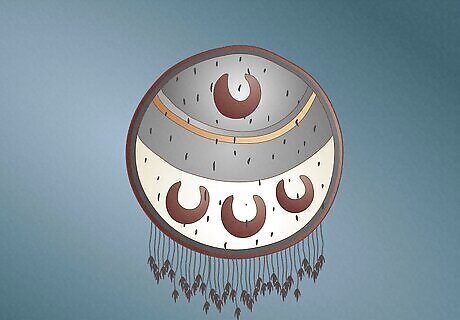

Chimalli (round shield) Thechimalli was an Aztec warrior’s shield from enemy blows. The shield was circular and could be made from wood (cuauhchimalli), maize cane (otlachimalli), or other materials (for example, some ceremonial shields were made of feathers (māhuizzoh chimalli)). The shields were often adorned with paint, designs, feathers, or leather strips and were an important Aztec cultural symbol.

Ichcahuipilli (body armor) Aztec armor was made of multiple layers of quilted cotton, soaked in saltwater to add extra stiffness and make the material more resistant to enemy blows. It was often 1-2 fingers thick and could reduce or protect against damage from darts or amacuahuitl. Some elite warriors also wore an ēhuatl (“skin”), or tunic, over their armor.

Tlahuiztli (prestigious warrior suit) These battle suits served 2 purposes: to make theichcahuipilli more effective by adding additional protection over the torso and limbs, and to identify an elite soldier’s rank and battle achievements, alliance, and/or social status. They were typically colored and decorated according to the warrior’s rank and were made of a combination of animal hide, leather, and cotton.

Cuacalalatli (helmet) Aztec helmets were usually made from local wood and covered the head and jawline. They were often carved to resemble animals, with the warrior’s face appearing in the animal’s open mouth. Helmets were most often worn by elite warriors (such as Eagle or Jaguar warriors) and were decorated according to the soldier’s warrior class.

Warfare in the Aztec World

The Aztecs waged war to expand their influence and capture human sacrifices. War was a central part of Aztec society and served 2 primary purposes: to conquer new city-states and collect their resources (or quell rebellions in previously conquered areas), and to collect sacrificial victims to honor their gods. They were so fearsome in battle that at the height of their power, they extracted tribute from 371 different city-states! Most Aztec war campaigns fell into one of two categories: Coronation wars: These campaigns were waged by the new tlatoani (leader of the Aztecs) when they assumed power to assert their dominance over other city-states, acquire new territory, and prove their prowess in battle. Flower wars: These campaigns were conducted specifically to collect sacrificial victims. Often, both sides would agree to do battle beforehand, with the assumption that the losers would provide warriors for the other side to sacrifice.

All Aztec boys were trained for warfare from a young age. The Aztecs had no standing army—all men were trained in warfare from a young age and could be called upon to fight on behalf of the Empire. Commoners made up the bulk of the army and were trained at the telpochcalli, or the neighborhood school for commoners. The sons of the elites were also trained for war (as well as to become military leaders, priests, and government officials) at the calmecac, or elite school for the nobility. What about Aztec women? Aztec women were often in charge of the home and domestic affairs, but were also considered warriors in a way. Childbirth was considered a battle, and women who passed away during childbirth were believed to join men who fell in battle in the afterlife.

Warfare was one of the few ways for men to climb the Aztec social ladder. Even if they weren’t born elite, commoners who were gifted soldiers could rise through the ranks and enter the same Aztec warrior classes as the nobles, often receiving gifts and titles as rewards for bravery or capturing a significant number of sacrifices. Commoners in the army were organized into wards commanded by the tiachcahuan, or leader, while nobles were organized into professional warrior societies. Both nobles and commoners could climb the ranks of these societies: Tlamanih: Commoners who had taken one captive. Cuextecatl: Soldiers who had taken 2 captives and wore conical hats with red and black tlahuiztli. Papalotl: Soldiers who had taken 3 captives and wore a butterfly-like banner on their backs. Jaguar and Eagle warriors: Soldiers who demonstrated the most bravery and skill in battle. They wore jaguar skins or eagle feathers during battle to take on the attributes of those animals. Otōntin (Otomies): A celebrated warrior class named after the Otomi ethnic group renowned for their fierce fighting. Cuachicqueh (The Shorn Ones): The most prestigious warrior class, requiring 6 or more captives and other heroic deeds. They shaved their heads but left one long braid over their left ear and painted their faces half-blue and half-red or yellow.

Battles typically began at dawn and ended when a city’s temple was sacked. Most battles were fought on large plains, and the two armies would begin by facing each other with lots of shouting, posturing, drumming, smoke signals, and other intimidation tactics. When it was time to fight, projectile weapons and rocks would be thrown first as the two armies approached one another. Then, the most elite of the Aztec warriors would enter the fray first with melee weapons, followed by decreasingly prestigious ranks (all the way down to commoners and trainees). The goal of battle was usually to maim or injure an opponent enough to capture them as a sacrifice, rather than kill them on the battlefield (although this definitely did happen too). The battle usually ended once the enemy city’s temple was taken. The city would survive if it pledged to join the Aztecs and pay regular tribute and taxes. If not, it would be destroyed. Captured soldiers were taken back to the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, to be sacrificed to the gods in a special combat ritual. Aztec soldiers who died in battle were ritually burned on the battlefield instead of being returned home. Their family would then enter an 80-day period of ritual mourning.

Comments

0 comment