views

Finding Bond Order Quickly

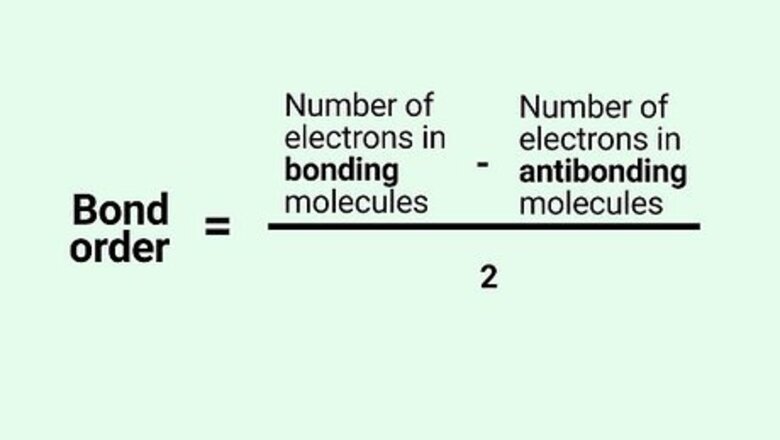

Know the formula. In molecular orbital theory, bond order is defined as half of the difference between the number of bonding and antibonding electrons. Bond order = [(Number of electrons in bonding molecules) - (Number of electrons in antibonding molecules)]/2.

Know that the higher the bond order, the more stable the molecule. Each electron that entered a bonding molecular orbital will help stabilize the new molecule. Each electron that entered an antibonding molecular orbital will act to destabilize the new molecule. Note the new energy state as the bond order of the molecule. If the bond order is zero, the molecule cannot form. The higher bond orders indicate greater stability for the new molecule.

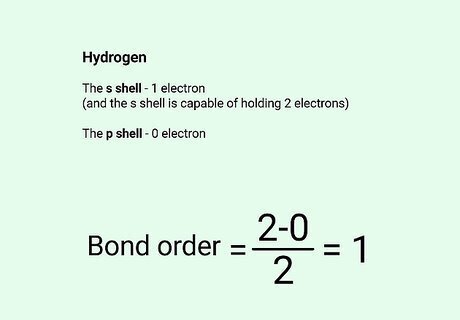

Consider a simple example. Hydrogen atoms have one electron in the s shell, and the s shell is capable of holding two electrons. When two hydrogen atoms bond together, each completes the s shell of the other. Two bonding orbitals are formed. No electrons are forced to move to the next higher orbital, the p shell – so no antibonding orbitals are formed. The bonding order is thus ( 2 − 0 ) / 2 {\displaystyle (2-0)/2} (2-0)/2, which equals 1. This forms the common molecule H2: hydrogen gas.

Visualizing Basic Bond Order

Determine bond order at a glance. A single covalent bond has a bond order of one; a double covalent bond, a bond order of two; a triple covalent bond, three – and so on. In its most basic form, the bond order is the number of bonded electron pairs that hold two atoms together. For a more in-depth look, check the periodic table to see what kind of bonding you've got going on.

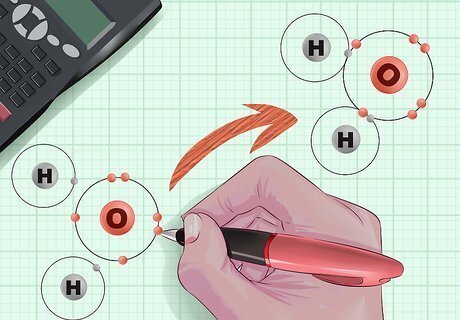

Consider how atoms come together into molecules. In any given molecule, the component atoms are bound together by bonded pairs of electrons. These electrons revolve around the nucleus of an atom in "orbitals," each of which can only hold two electrons. If an orbital is not "full"—i.e., it only holds one electron, or no electrons—then the unpaired electron can bond to a corresponding free electron on another atom. Depending on the size and complexity of a particular atom, it might have only one orbital, or it might have as many as four. When the nearest orbital shell is full, new electrons start to gather in the next orbital shell out from the nucleus, and continue until that shell is also full. The collection of electrons continues in ever-widening orbital shells, as larger atoms have more electrons than smaller atoms.

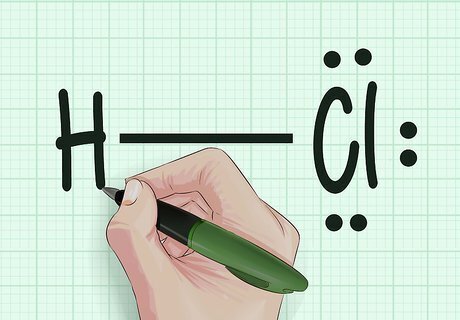

Draw Lewis dot structures. This is a handy way to visualize how the atoms in a molecule are bonded to one another. Draw the atoms as their letters (e.g. H for Hydrogen, Cl for Chlorine). Illustrate the bonds between them as lines (e.g. – for a single bond, = for a double bond, and ≡ for a triple bond). Mark the unbonded electrons and electron pairs as dots (e.g. :C:). Once you've drawn your Lewis dot structure, count the number of bonds: this is the bond order. The Lewis dot structure for diatomic nitrogen would be N≡N. Each nitrogen atom features one electron pair and three unbonded electrons. When two nitrogen atoms meet, their combined six unbonded electrons intermingle into a powerful triple covalent bond.

Calculating Bond Order for Orbital Theory

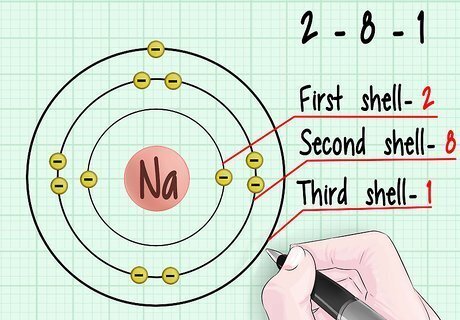

Consult a diagram of electron orbital shells. Note that each shell lies further and further out from the nucleus of the atom. According to the property of entropy, energy always seeks the lowest possible state of order. The electrons will seek to populate the lowest orbital shells available.

Know the difference between bonding and antibonding orbitals. When two atoms come together to form a molecule, they seek to use each other's electrons to fill the lowest possible states in the electron orbital shells. Bonding electrons are, essentially the electrons that stick together and fall into the lowest states. Antibonding electrons are the "free" or unbonded electrons that are pushed to higher orbital states. Bonding electrons: By noting how full the orbital shells of each atom are, you can determine how many of the electrons in higher energy states will be able to fill the more stable, lower-energy-state shells of the corresponding atom. These "filling electrons" are referred to as bonding electrons. Antibonding electrons: When the two atoms try to form a molecule by sharing electrons, some electrons will actually be driven to higher-energy-state orbital shells as the lower-energy-state orbital shells are filled up. These electrons are referred to as antibonding electrons.

Comments

0 comment