views

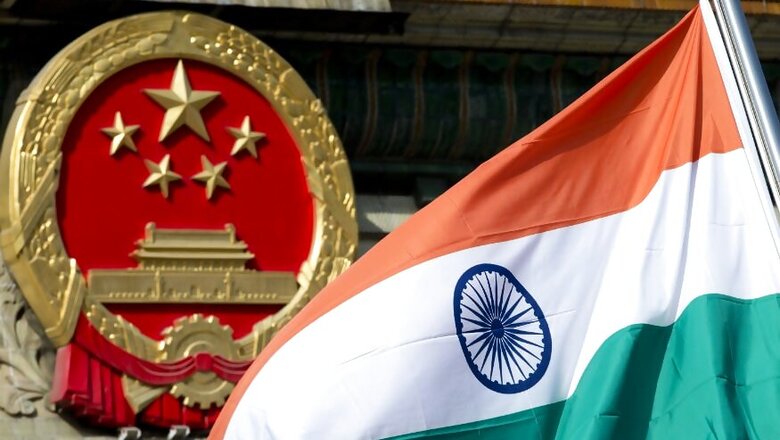

New Delhi: The Sino-Indian bhaichara has at best been flimsy through the years. As it is, bilateral trade is heavily skewed in China’s favour, with India’s trade deficit in the April 2019-February 2020 period surpassing 43 billion dollars. There are numerous instances of India imposing anti-dumping duties against Chinese imports to safeguard Indian industry and there have been years when even Diwali lights across Indian homes have become the subject of heated discussions and boycott calls, since they largely come from China. Not only in trade, the two countries have had their share of disagreements in other areas as well, the most recent being China’s ‘Belt and Road’ initiative from which India has kept away.

Now, as the Covid-19 pandemic brings about a tectonic shift in geopolitics and global trade, India cannot remain unaffected by either the resurgence of China in world trade or the fact that Chinese companies may make further investments in Indian businesses. So India has decided to raise its walls against any impending takeover of homegrown firms by making any such future investments from China subject to government scrutiny first.

This is a welcome move, as long as it is a short term measure to protect vulnerable Indian businesses and does not become a tool to keep China out permanently from making further investments here. Because this could, in theory at least, also impede future investments by Indian firms in China, besides causing friction in already strained bilateral trade relations. We need to remember that Indian industry is heavily dependent on China for supplies in some sectors. Also, in the long term, India could make an exception perhaps for investments coming into new infrastructure projects and other large areas by allowing these through the automatic route.

Before going any further, it is pertinent to examine what the government data tells us about the extent of Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in India. According to official data, FDI from China should cause no serious concern for us. In the last 19 years, FDI inflows from China have accounted for just half a percent of the total inflows. China is at the 18th place in the FDI pecking order, with inflows between 2000 and 2019 just under Rs 15,000 crore. This means not even Rs 1,000 crore came from that country into India on an average each year. Mauritius and Singapore together have accounted for nearly half the FDI inflows into India during these 19 years.

So what explains the paranoia which gripped the Indian government over the prospect of increasing takeover threat for Indian businesses from Chinese predators

According to this press note issued on Saturday, the government amended the existing FDI policy – which largely allows for FDI inflows through the automatic route, requiring no prior vetting from the government – to curb “opportunistic takeovers/acquisitions of Indian companies due to the current Covid-19 pandemic”.

As per the new norms, an entity of a country which shares land border with India, or where the beneficial owner of an investment into India is situated, or where the owner of such an investment is a citizen of any such country, can now invest only under the government route. Though the government note does not mention China by name and similar restrictions have always applied to investments from Pakistan and Bangladesh, the reference to Chinese investors is quite obvious.

So why is the Indian government worried about Chinese predators stalking Indian companies, which are already down in the mouth due to economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and resultant crash in their valuations?

The proverbial last straw could have been the purchase of 1.75 crore shares of HDFC Bank by China’s People’s Bank in the fourth quarter of fiscal 2020, which meant the Chinese company raised its stake in the Indian bank by 0.2% to 1% in HDFC Bank. This investment had prompted Congress leader Rahul Gandhi to exhort the government to protect Indian industry from further hostile takeovers by Chinese firms.

A research paper by a visiting scholar at Brookings India earlier had showcased the reasons for growing worries in India over Chinese takeovers. This paper said that till the BJP government’s arrival at the Centre (till 2014), the net Chinese investment in India was $1.6 billion and that most of the investment was in the infrastructure space. It largely involved major Chinese infrastructure players, predominantly state-owned enterprises.

“But, over the next three years, total investment by Chinese firms increased five-fold to at least $8 billion, according to data from the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) in Beijing, with a noticeable shift from state-driven to market-driven investment from the Chinese private sector,” the paper said.

If a five-fold increase in Chinese investments in India within a span of three years – the first three years of the current government at the Centre — isn’t alarming enough, consider this: the paper said the official figures quoted above have underestimated the amount of actual investment, “as they neither account for all Chinese companies’ acquisitions of stakes in the technology sector, nor investments from China routed through third-party countries, such as Singapore. For instance, a $504 million (Rs. 3,500 crore) investment from the Singapore subsidiary of the mobile and telecom firm Xiaomi would not figure in official statistics because of how investments are measured.”

So India did not fully document the total inflow of FDI from China from different sources. Neither did the BJP government, known for its Swadeshi rhetoric, make any move before Saturday to check the extent of Chinese investment coming in through various routes into Indian entities. So the Chinese threat continued growing. No wonder then that the official data of the 19-year period between 2000 and 2019 only show about $2.3 billion Chinese FDI inflows.

This report shows Chinese companies have made a whopping $4 billion investment in just the Indian tech space in just five years. The market leader in digital wallets – Paytm – is backed by China’s Alibaba, as is the leader in online grocery space, BigBasket. Urban mobility solution provider Ola also has sizeable investments from China and there are myriad other Indian fintech and ecommerce entities which are backed by well funded Chinese companies.

Now that a restriction has been imposed by the government, it is unlikely to affect the existing investments by Chinese firms – whether state-owned or private. It only puts a question mark over future investments by Chinese businesses.

Comments

0 comment