views

The culprits of the Delhi gang-rape are awaiting their noose. There is a clamour for the speedy execution of their hanging. It has opened the usual debate about the morality of retributive justice when the state executes a criminal.

The idea of retributive justice is neither new nor unique to India. Mirroring the old testament logic of an eye for an eye, ancient Indian laws also believed in state-sponsored violence as a means of deterrence. Arthasastra prescribes death penalties for many forms of adultery. Manu Smriti prescribes mutilation of fingers and other organs for rapists and if the rape victim dies, death by torture is the punishment recommended for the criminals.

The justice under various Indian dynasties, whether Hindu or Muslim, was mostly retributive. Cutting of hands, dragging the body by horse, stamping by elephants, impaling, beheading, castration, blinding and death by slow torture where one is eaten by crows and sparrows while lying immobilized inside a cage were the methods used for administrating justice. The British standardized the method of execution to death by hanging.

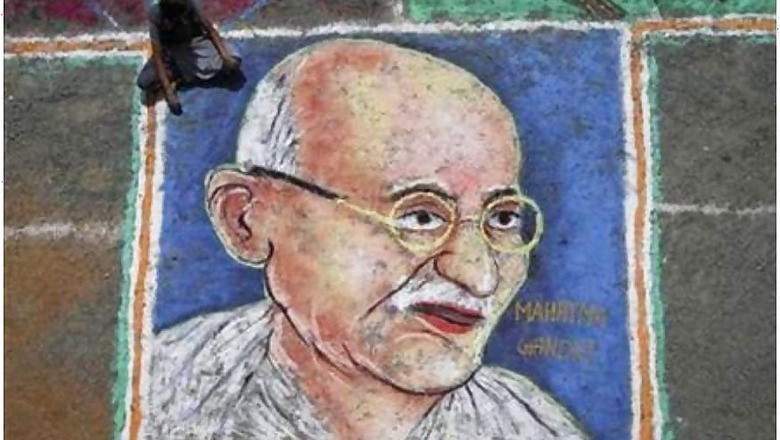

Though Article 21 has stated that the government has no right to take the life of any person and despite Mahatma Gandhi speaking vociferously against death penalty, India has continued the British era practice of capital punishment. The UN charter of Rights has declared death penalty as a crime against humanity and keeps asking its member countries to abolish it. Out of the 193 member countries, 170 states have abolished or introduced a moratorium on the death penalty either in law or in practice or have suspended executions for more than 10 years, as per UN secretary General’s report.

Unfortunately, the land of 'Ahimsa', the land of Buddha, Mahavira and Gandhiji is not one among them. India’s international stand on death penalty has always gone against the UN resolution. The argument that India puts forward is that the statutory law of the country, a British era legacy made for its colony, permits execution of the culprits in the ‘rarest of the rare’ cases.

The earliest possible reference for the concept of Ahimsa perhaps is in Chandogya Upanishad, where Ahimsa is listed as one of the five virtues. Tapa (penance), Danam (alms giving), Arjavam (honesty), Ahimsa (non violence) and Satyavachanam are the five Yajnas of life, proclaims this Upanishad, dated arguably to 8th century BC. However, the Upanishad gives an exception to Ahimsa. Himsa (aggression/violence) was permitted in Teerthas or pilgrim centers, indicating animal sacrifice. According to Manu Smriti, animal sacrifice leads a Dwija (twice-born) and the slaughtered animal to Uttama Swarga or the highest heaven.

Charvaka, the earliest known rationalist, mocked this offer of heaven for a slaughtered animal, by asking the Dwijas to slaughter their loved ones like their sons or parents and grant them the fortune of reaching the heavens, instead of wasting such fortune on beasts. In epics, though the characters sometimes espouse the virtues of Ahimsa, it is seen that violence was a way of life. The punishments were often arbitrary. In Uthara Ramayana, Lord Rama beheads Shambuka, a Shudra for the crime of doing penance, while in Mahabharata, the Brahmin Aswathamma, who sneaks into the army camp of Pandavas and sets it on fire and who kills the five sons of Pandavas in their sleep, is let off with a curse to roam around the world without peace. Ironically, the great epic of Mahabharata ends up as the greatest treatise against violence and Bhishma’s quote to Yudhishtra from his death bed of arrows, repeats Ahimsa Paramo Dharma.

Buddhism and Jainism rose in an environment where ritual sacrifice and slaughter had reached its peak. Jainism extended the concept of Ahimsa to all living creatures (Sarva Bhuta).

Ahimsa Parmo Dharma – Non-violence is the greatest virtue

The Indian reform movement declared the dharma of non-violence to the world, two and half millennia ago. While Jainism went to the extreme compassion of being worried about killing even Sukshma Pranas or creatures that can’t be seen with naked eyes and advised its followers to cover their nose and mouth to prevent them from accidentally entering one’s body and be killed, Buddhism chose the middle path. Jainism laid the foundation of vegetarianism in India.

The rise of Buddhism and its eventual spread across the world led to the concept of Ahimsa to spread beyond the Indian shores. Buddhism gave a theoretical base to Ahimsa. The objective of life was not only to show compassion but also Dukha Nivarana or the elimination of suffering of others. The famous Buddhist story of Angulimala illustrated how Buddha had illustrated the power of Ahimsa.

Anguli Mala was a notorious robber who killed wayfarers and made a garland out of their chopped fingers. No one dared to walk through the highway in the night, fearing Anguli Mala. One day, he saw a monk walking alone through the path and chases him. Try as he might, the robber was unable to catch up with the calmly walking monk. The robber asked the monk to stop. The monk turned out to be none other than Buddha. He halted and said compassionately, ‘I have stopped long ago. Why are you still running?’ The profound words had a deep impact on Anguli Mala. He followed Buddha like a tame dog and became a monk.

Meanwhile, the King heard of the discourse of Buddha and expressed his concern about his inability to catch robbers like Anguli Mala. While the former robber was ready to surrender, Buddha told the King that Anguli Mala was dead and the man before them was a new man. There was no one who cannot mend their ways. Buddha advised the King to use compassion and kindness as the measure of delivering justice.

The delivery of justice shouldn’t seek revenge but provide reform. The duty of an individual and the society is to provide the elimination of suffering. By making the culprit suffer, the suffering of the victim doesn’t reduce. It would only add to more sufferings in the world. Buddha said the roots of Ahimsa is in the mind. Evil and violent thoughts always precede violent deeds. Any punishment should aim to eliminate the sin and not the sinner. The idea of Ahimsa spread across the world through Buddhist proselytization and conversions. The Buddhist monks took Ahimsa to Sri Lanka, and far east to China and Japan and later it influenced Christianity. Thus, for a better part of human civilization, India remained the light that guided a world torn apart by crusades and religious wars.

After the decline of Buddhism in India and the revival of post-Buddhist Hinduism in which vegetarianism was appropriated by the Brahmins, the concept of Ahimsa took a back seat in India until Mahatma Gandhi rediscovered it. Once again, India’s concept of non-violence influenced the great minds across the world, inspiring Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela and Dalai Lama.

India’s greatest contribution to the world is not ‘Zero’, but the concept of Ahimsa. Mahatma Gandhi always objected capital punishment as he was convinced about the futility of the same. It neither provides deterrent nor does it give solace to the victim. At the peak of partition riots, a justifiably angry Hindu who had lost his son to a Muslim mob asked Mahatma Gandhi how he would calm his mind when he thirsted for revenge against his son’s killers. Gandhiji advised him to adopt a Muslim boy orphaned in the riots and bring him up as a Muslim. The advice to the Muslim parents who had lost their children in the riot was to adopt orphaned Hindu boys and bring them up as Hindus. On retributive justice, Mahatma Gandhi said, an eye for an eye would make the entire world blind.

State sponsored killing of any murderer is no deliverance of justice. It is just a proclamation that murder is alright if it is done by the State. It neither deters the criminal nor does it stop the crime. Instead, as Buddha had warned, it just increases the amount of suffering in the world.

A life term in prison the real sense of the word, to the culprits, would be a more humane approach than execution, in the land of Gandhiji and Buddha. The society that celebrates the brutal murder of the accused without trial by the Police, as it happened following the Hyderabad gang-rape, can’t be expected to remember Buddha or Gandhi. Bapu, like Buddha, is an inconvenient icon for the masculine nationality that considers such an act of compassion as effeminate. While the world is marching from darkness to light, we are marching from light towards the night of Medieval Europe, marked by religious strives, violence and rabid nationalism.

The writer is an author, columnist and TV personality. Views expressed are personal.

Comments

0 comment