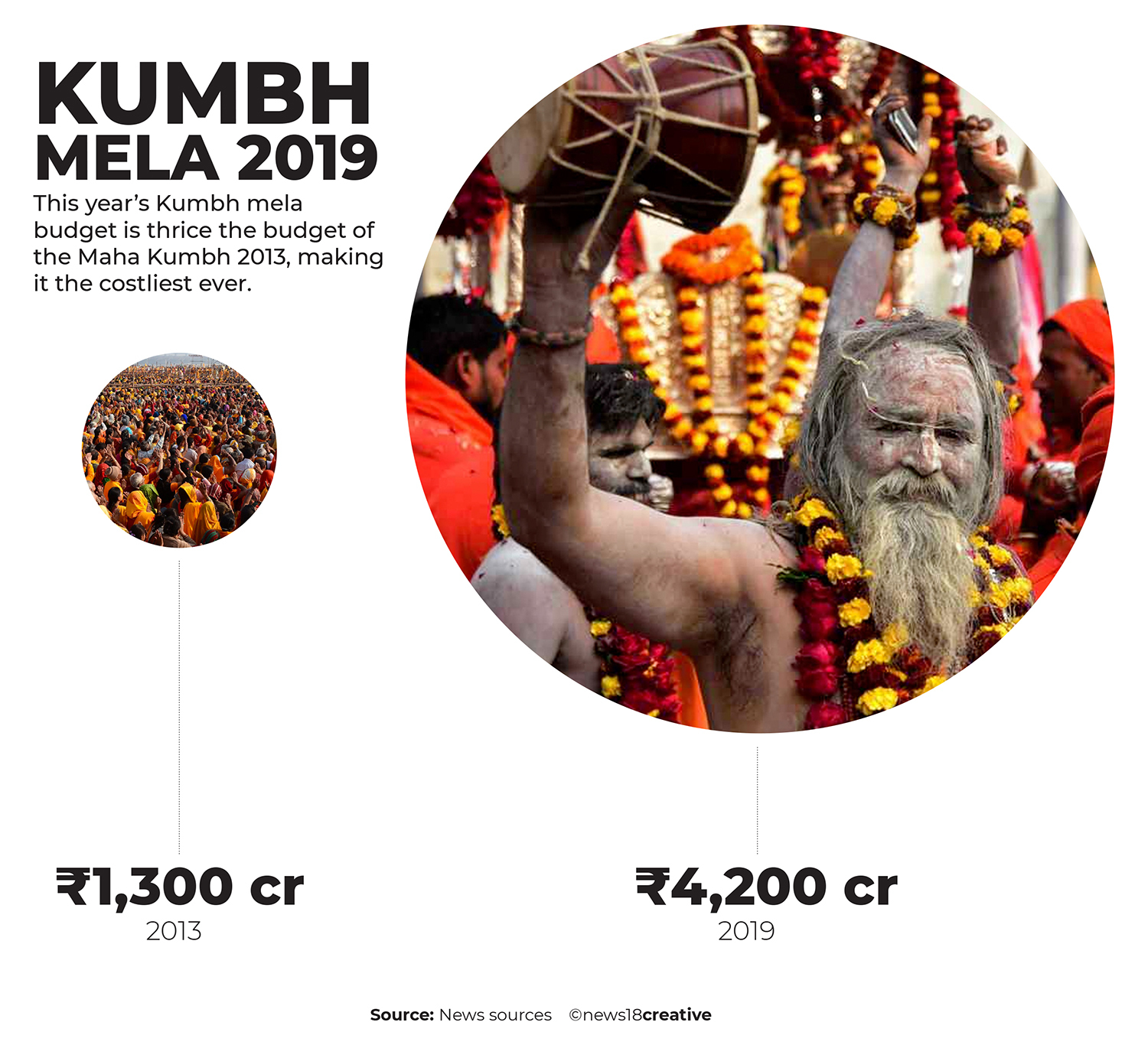

views

Prayagraj: A Dalit farmer, a Muslim tea seller, and a housewife who works as a part-time tailor; all wearing red flashy plastic coats and cloth caps, strolling along the banks of Sangam at Kumbh with a broom in their hand. What else do they have in common?

They are among the thousands of sanitation workers who have been tasked to keep the Kumbh clean. Young and old, men and women, these are the people often with little in common except their desire to add good karma to their lives and earn some extra money to raise their family.

The 150 million strong religious gathering, all three of them believe, gives them the both.

The workers are tasked to clean the offices of various organisations, the ghats, camps and other public utilities, apart from the roads that lead to Sangam (News18.com)

Beyond Social Barriers

Since decades, Sanjay Kumar, has wanted to surmount his caste-based identity and find fulfillment through honest work. Being a Dalit, his situation epitomizes the plight of the lower caste people in India’s hierarchical caste-based society.

But at the Kumbh this year, where his job is to clean Sangam, he is respected for his work.

Kumar, a farmer by profession, suffered severe social discrimination as he went about his daily work of cleaning toilets in Dausa, Rajasthan during last two decades. This year, however, his decision of coming to Prayagraj and work as a sanitation worker has finally given him the “status” he always aspired.

“People don’t ask you about your caste or religion here. Nobody discriminates you,” Kumar, a 40-year-old father of three, said.

He further emphasised that this recognition by the pilgrims that descend to Kumbh is “a manifestation of the real confluence of human identity in a pandemonium of faith and religion that this religious gathering is known for.”

Kumar is one among the many sanitary workers and garbage compactors which will help Prayagraj Mela Authority achieve the government’s target of organising a ‘Swachh’ Kumbh this year. Divided into 950 teams, this battery of an estimated 11,400 people has been tasked to clean the offices of various organisations, the ghats, camps and other public utilities, apart from the roads that lead to Sangam.

To make sure this mission is achieved, the authorities have roped in ‘Safai Karamcharis’ from different regions across the country. These foot soldiers — men and women — away from the societal barriers and the media blitzkrieg that has taken over the congregation, are making sure the ‘world’s largest religious gathering’ remains garbage free.

The foot soldiers are ensuring that the 'world's largest religious gathering' remains garbage free (News18.com)

However, with almost 150 people million expected to take part in the one and half month long congregation, keeping the arena clean is a herculean task.

This year’s Kumbh would be organised on an area of 3,200 hectares, which would be divided into 20 sectors. To assist these sanitation workers, the authorities have also put across over 20,000 dustbins across the Mela ground. But the real work to keep the congregation expanse clean lies with the workers.

For a Greater Good

Wilayat Khan is a Muslim resident of Banda district in Uttar Pradesh where he sells tea. 160 kilometers away from his village, Khan wakes up at 4 AM in the morning and heads towards the Sangam. Part of a ten-man squad — working under a leader who keeps check on their work — Khan’s job is remove any solid waste that he finds on the dusty banks of Sangam.

Almost every 15 minutes, Khan patrols the area he is assigned and keeps a look out for the waste, if any. It rarely happens when Khan doesn’t find any solid waste during his patrol.

“So many people walk on the Sangam banks. They eat their food, drink water from plastic bottles and throw away the waste. It’s an endless cycle of picking ups the waste and throw in the dustbins,” Khan said.

For this task, Khan, who is in his 60s, is paid a sum of Rs 400 per day. Like everyone else, he has to work a 10-hour shift with small breaks every once in a while. For Khan, the stipend at the end of the day’s work is satisfactory.

“I have understood that the work I am doing is more important than money. I am tending to the guests who come to perform their religious duties and that’s what makes me happy,” Khan said.

He is happy that the work this year isn’t as nauseating as it was earlier, when he had to clean human excreta with a broom from temporary pit toilets built on the banks of Sangam. The faeces had to be collected, bit by bit, in a basket, carried on the head, and then hurled into a wheelbarrow.

However, working for ten hours can be exhausting for the sexagenarian. But he believes there is a greater good in this service. “When you see a smile on the face of a pilgrim, all the tiredness vanishes and you feel happy and contended. That is the best feeling,” he said.

A Thankless Job

Yet, for many like Khan, most of who come from the marginalised communities with little money, few provisions and nowhere to sleep, keeping the Kumbh clean is a “thankless job.”

A female worker who hails from Madhya Pradesh echoes this concern.

Mithali Kumari, 49, has been coming to Kumbh during the 'Shahi Snan' gatherings for over five years now. A part-time tailor, Kumari doesn’t deny the cordial behavior towards her and other cleaning workers by the worshipers. But the official apathy and the lack of facilities for them is what bothers her.

Like most of these workers, Kumari also lives with her family in a makeshift tent on the banks of Sangam. Lack of drinking water and proper bedding — something that was promised to her by the authorities when she was hired for the 45-day long period — is giving her daily troubles.

“We clean people’s excreta from the toilets, make sure the holy place doesn’t stink, but our justified needs are falling on deaf ears,” she said.

Kumari was also quick to qualify her concerns. “The authorities don’t provide necessary equipment and we are compelled to clean toilets by hand or only broom. We aren’t even given any masks or gloves.”

For many like Kumari, keeping the congregation area clean is the most tiring thing to do. From carrying and disposing of human excreta from the makeshift toilets to cleaning the left overs that the pilgrims leave behind during the congregation, the ‘Safai Karamcharis’ like her do it all.

But being a sanitation worker at the Kumbh, however, serves two purposes for Kumari: one, she gets to earn livelihood for her family of six members; second, she keeps the congregation area clean to earn Punya, which can be loosely translated as good karma.

"We are not here only to earn a livelihood. We think that if we keep the Kumbh clean, God will change our life," Kumari said.

Comments

0 comment