views

New Delhi: One of the saddest stories last year was reported from a children’s shelter home in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur district. An audit of the shelter homes ordered by the state’s welfare department exposed systematic and institutionalised sexual abuse of children, particularly of girls lodged at ‘Seva Sankalp Ewam Vikas Samiti’.

Of the 42 girls lodged in this shelter home run by one Brajesh Thakur — a man with some political clout who has since been arrested — 34 girls were found to have been sexually abused. The CBI, which later took up the case from local police, found that five girls had also been murdered in this shelter house. One girl, who is rumoured to have refused to be raped, was allegedly bludgeoned to death in front of the other inmates as a warning.

According to a national daily, in a ‘supervision report’ filed by the town DSP, the accused Brajesh Thakur “ran a sex racket and supplied girls to officials to get tenders” for government projects.

Seva Sankalp was the worst but not the only of its kind. Several other cases of shelter homes where people in power routinely traumatised the children they were in charge of, were revealed based on the audit report commissioned by Atul Prasad, principal secretary in Bihar’s social welfare department.

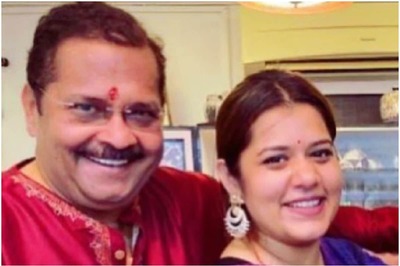

For the first time since this story broke, Prasad gives News 18 an in-depth interview explaining why he commissioned the audit, the ingenious ways in which he tried to overcome the system to ensure that it wasn’t lost in government files, and about how the victims are coping with the trauma.

What was the reason behind commissioning an audit of your state’s child shelter homes?

Since joining bureaucracy I’ve come to realise one thing, the lack of any report is a bad omen. This is the sense I got from our child shelter homes as well. On paper, everything seemed quite in place. Other times there were no reports. Something was rotten in the system and I wanted to know precisely what it was.

We know that a lot of children are abused by those who are very close to them. A question that always lingered in my mind was, if children can be abused at home what prevents their abuse in a shelter home?

Then what?

I also knew that most auditors in the country only look at finances of state-sponsored shelter homes when they are sent on audits. The shelter homes are encouraged to keep their books clean and those with the necessary vouchers keep getting the money. I mistrusted this system of evaluating the quality of the shelter homes. I wanted to know the lived experience of the children who were in very vulnerable situations.

Did you suffer any interference, political or otherwise, from this audit?

Not really and the reason perhaps is that I foresaw some of the difficulties. For instance, I decided to get all the shelter homes audited, not just one or two. Secondly, I did not pay a penny to the team from TISS which agreed to do this audit. We only took care of their accommodation, put them up in dharamshalas.

Whatever became of this audit, I knew that nobody would be able to point fingers at us or the authenticity of the audit, and accuse me of corruption or favouritism. Even later on, when people asked me questions, I had all the answers.

So what happened when you received the report?

The first thing we did was we got children in the shelter homes — where they were being abused — shifted to safer places. We did this discreetly so that people even from our own department did not know why children were being shifted. This was necessary because clearly some of our own people were involved.

The report was sent to us as a soft copy written in English. We did not know the full extent of the abuse or neglect but were able to identify the problematic shelter homes. So I called my officers from social welfare department across the state to our headquarters in Patna, made them listen to a presentation, distributed the copies, and asked them to act immediately. I did not want this report to die in official files.

Only after the children were shifted to safer places did we hand over the case to police and a criminal investigation began. We ensured that nobody was spared. Some of my own officers were arrested. One officer from the child welfare committee, whose role was to check the working of shelter homes and report anomalies, was also arrested.

The media did not know about it initially. Within days of police investigations, 10 out of 11 accused were arrested. The action was actually pretty quick. This happened in May end. Only after media got the whiff of it did the whole extent of abuse come before the public eye.

How are the abused children doing now? What about their counselling and rehabilitation?

Rehabilitation is the main issue. Their trauma increased when the media people began talking to the victims, making them recount their ordeal again and again and pushing them over the edge.

I haven’t interacted with any of the victims, but I’ve heard that their trauma plummeted to such depths that some of them refused to talk to anyone. They came a stage when they started slashing their wrists to kill themselves. They are right now undergoing treatment from the best counsellors, and will hopefully recover to some extent soon.

What do you personally feel about the whole episode? What is your take away from it?

I still shiver sometimes when I think about what happened in Muzaffarpur and other shelter houses. It was unimaginable. We were very angry when we came to know that these crimes were happening for the last several years. But there is some satisfaction in knowing that we finally put an end to it. So I am left with mixed feelings about it.

Hopefully, many other states will initiate such social reforms. This will pave way for far-reaching reforms across the country.

Comments

0 comment