views

New Delhi: Observing that there cannot be an absolute injunction against the State from enacting a law, the Supreme Court on Tuesday sought to know what could be the contours of the right to privacy and the nature of restrictions that could be imposed on exercising this right.

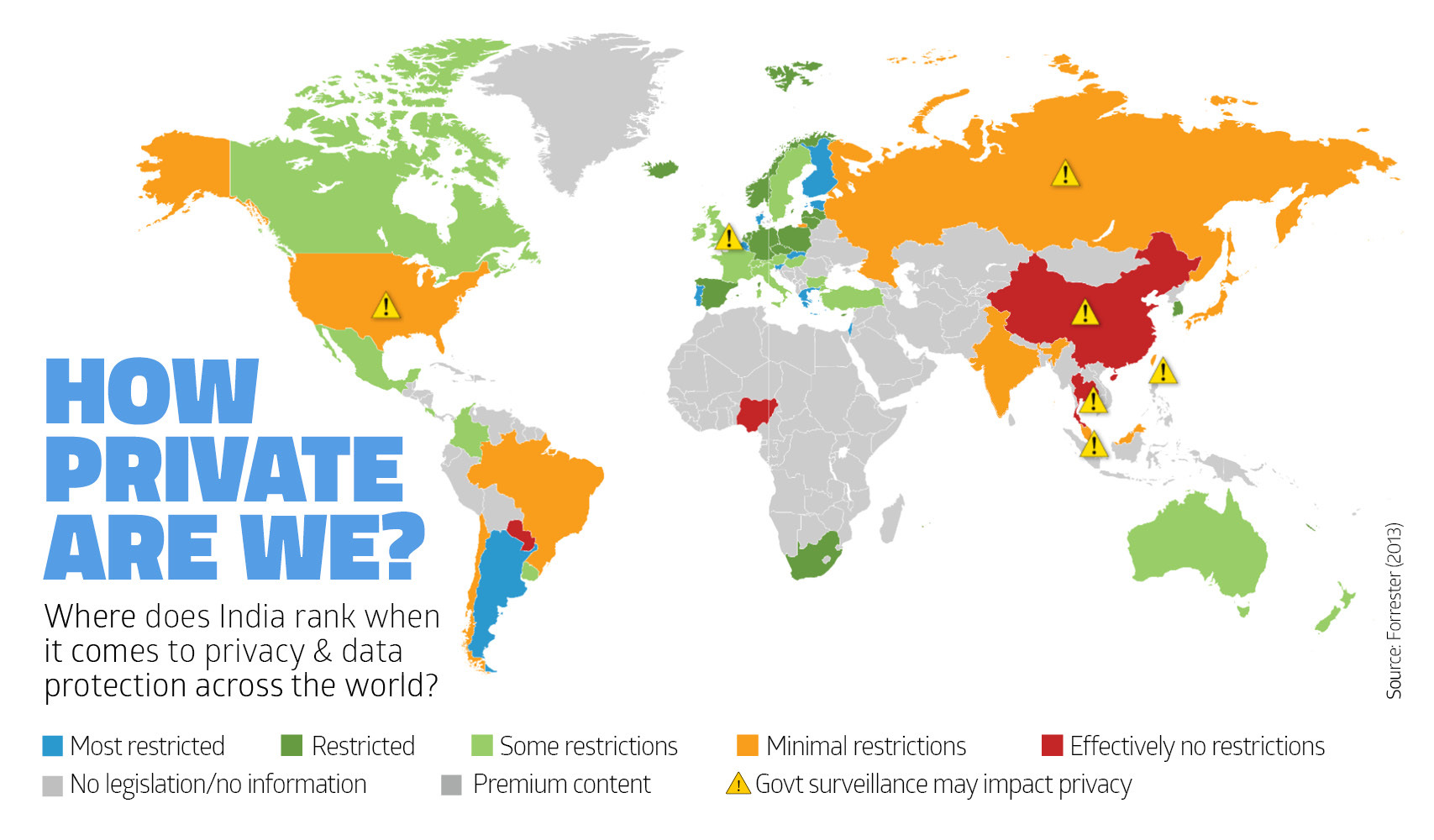

A nine-judge bench headed by Chief Justice of India J S Khehar further observed that in this digital era, it was not possible to assert an "overarching" right to privacy or right to data protection.

Senior advocates Soli Sorabjee, Gopal Subramanium, Shyam Divan and Arvind Datar argued in favour of recognising right to privacy as a fundamental right.

They submitted that privacy is an intrinsic facet of liberty, and that it is a pre-existing natural right which only requires a recognition by the apex court. "Privacy is embedded in all processes of life and liberty... what's privacy except liberty? Privacy is an inalienable natural right. It is heart and soul of Constitution. Privacy signifies will of individuals," argued Subramanium.

He added the issue was not about expansion of rights but recognition of an existing right. "Everything that an individual does in exercise of all his rights is attributable to privacy... it is inherent in right to liberty and dignity," said Subramanium.

On their part, Divan and Datar sought to press that the previous eight-judge and six-judge bench judgments about right to privacy not being a fundamental right were not only incorrect but they could not be treated as precedents since the issues before them were not sanctity of privacy right.

However, judges on the bench sought to know what would be the contours of 'privacy' if the court were to recognize this as a fundamental right. "Do you want to postulate privacy as an overarching right? Can a person not surrender his right? Or will it be defined by a constitutional limitation," asked the bench. It also sought to know of privacy essentially meant right to be left alone or something more.

During the day-long hearing, Justice Chandrachud further asked: "Can we say there is right to privacy but do not give an exhaustive list of what they are?"

The judge also questioned the proposition that every right under liberty will include privacy. "Every instance of making a decision will not necessarily entail right to privacy. Every element of liberty is not privacy. Whether I cohabit with my wife in the bedroom of my house is definitely an example of liberty where privacy is involved but whether I send my kid to a school or not is not a matter of privacy," Justice Chandrachud said through illustrations. He said privacy is a small subset of liberty.

Data protection and right to privacy:

The bench also made certain observations regarding data protection vis a vis right to privacy. Justice Chandrachud said that right to data protection may not be included in the right to privacy.

"Right to data protection is a much wider right. It has a wider ambit than right to privacy," he said.

The judge added that right to privacy, in his opinion, could not pre-empt right of the State to legislate. "Right to privacy cannot pre-empt State action. It cannot be considered as an absolute right. The right cannot be so overarching that it will prevent the State from legislating," said Justice Chandrachud.

The court will on Thursday hear Attorney General K K Venugopal on this point.

The issue cropped up after petitioners against Aadhaar claimed that collection and sharing of biometric information was a breach of their "fundamental" right to privacy. They argued that the Constitution has to be read as a dynamic document, requiring interpretations to suit modern times.

But the Centre has said right to privacy could not be assigned the status of a constitutional right and that it was only a common law principle. The government has relied upon two judgments to assert its position.

In MP Sharma case, the eight-judge bench ruled in 1954 that the right to privacy cannot be a fundamental right. That judgment held that when the Constitution-makers chose not to prescribe for constitutional limitations by recognising the fundamental right to privacy, "there is no justification for importing into it, a totally different fundamental right by some process of strained construction".

Another SC judgment by a six-judge bench in 1963 held that "the right of privacy is not a guaranteed right under our Constitution".

Comments

0 comment