views

What is queer coding & how does it work?

Queer coding is when a character has queer qualities but isn’t explicitly labeled as queer. Lazine says, “Queer coding … refers to the practice of implying a fictional character is queer in some way. [This is done] through attributes or characteristics commonly associated with the queer community, but without explicitly saying … a character is queer.” Popular examples of queer-coded characters include Team Rocket’s James from Pokémon, Scar from The Lion King, and HIM from Powerpuff Girls. Queer coding can be obvious or subtle. “Most commonly, you’ll see cis gay male characters in media portrayed with the stereotypical “gay accent” and being flamboyant,” says Lazine. “But [queer coding] can be as subtle as having a pride flag in the background of a character’s room or having the character be interested in hobbies common of some subset of the community, i.e. a transfeminine character that's coded as such through [knitting] needles in the background, being interested in programming, and enjoying tabletop games.” Queer coding can be used both positively and negatively. Positively, queer coding can provide affirming, empowering representation. Negatively, it can reinforce stereotypes. Meet the wikiHow Expert Mira Lazine is a journalist who specializes in LGBTQ+ issues, politics, science, and more. She’s been featured in outlets including The Washington Post and The Advocate.

Queer Coding Examples

Examples from the early 20th century include Captain Hook and Maleficent. Queer coding’s extensive history has made way for plenty of (potentially) queer characters. While many of those characters were written as villains, queer people have reclaimed them for the representation they bring to the table. Some of these queer coded characters include: The Cowardly Lion from The Wizard of Oz (1939) Captain Hook from Peter Pan (1953) Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty (1959) The Cheshire Cat from Alice in Wonderland (1951) Shere Khan from The Jungle Book (1967) Kaa from The Jungle Book (1967)

Disney was behind many of the examples from the late 20th century. Even after the Hays Code was officially suspended in 1968, overt queer representation was still rare and not publicly embraced for a few decades. Some queer coding was unintentional, but it's speculated that a lot of it was done purposely by queer writers and creators. Intentional or not, queer folks identified with these characters and claimed them, including: Darlene Conner from Roseanne (1988) Ursula from The Little Mermaid (1989), who was inspired by the drag queen Divine. Jafar from Aladdin (1992) Scar from The Lion King (1994) Billy Loomis and Stu Macher from Scream (1996) Hades from Hercules (1997) Ruby Rhod from The Fifth Element (1997) Li Shang from Mulan (1998) HIM from Powerpuff Girls (1998) Larry 3000 from Time Squad (1997-2005) Governor Ratcliffe from Pocahontas (1995)

Queer coding has persisted through the 2000s and beyond. There are still many characters who tow the line between openly queer and queer presenting, but their portrayals have become more accepting over time. Whether it be the ever-so-teased romance between Rouge and Topaz from Sonic X or Santana from Glee's gradual transition from queer-coded to openly queer, this persistence has resulted in characters like: Ryan Evans from High School Musical (2006-2008) Shego from Kim Possible (2002) Elsa from Frozen (2013) Luca and Alberto from Luca (2021) Raya from Raya and the Last Dragon (2021) Dr. Stone from Sonic (2020)

History of Queer Coding

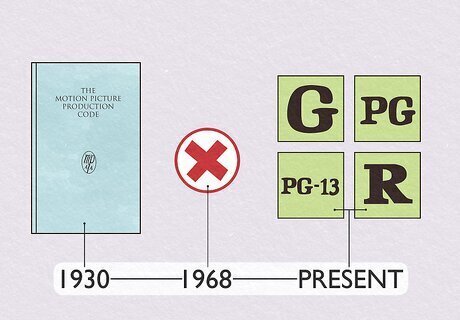

Queer coding became prominent after the Hays Code in 1930. The Hays Code (formally known as The Motion Picture Production Code) was a set of motion picture industry guidelines that prohibited certain types of content from being shown in films, including the portrayal of homosexuality. But, characters were still allowed to be portrayed in androgynous ways that didn’t overtly spell out their queerness, but rather alluded to it. This resulted in an influx of queer coded characters following the law. For example, Alfred Hitchcock famously portrayed queer-coded characters in at least 10 of his films, including Mrs. Danvers from Rebecca (1940) and Brandon and Philip from Rope (1948). Oftentimes, villain characters were queer coded, which may have created some negative perceptions about the queer community. The Hays Code was repealed in 1968 following the Civil Rights Movement. It was replaced with the current MPAA rating system we know today.

Queer coding existed before and after the Hays Code, as well. “The history of [queer coding] is ancient,” says Lazine. “Examples of implications of queerdom was seen before there was even a word for such. [In] modern history … it can be traced back to mainstream attention to queer individuals in the late 20th Century. Examples [can be] seen throughout television, film, and comics.” “There are countless examples,” adds Lazine, “and it has indeed been prevalent for decades, if not centuries.”

Positive & Negative Impacts of Queer Coding

Some people believe that the subtle queer representation was a good thing. “[Queer coding] has been somewhat favored, if critically, by the queer community,” says Lazine. “While many do appreciate how it can be valuable to signal a character (and thus the media creators’ alignment with our community), many more criticize queer coding for not going far enough in explicitly showing a queer individual’s identity.” “After all,” Lazine continues, “many say we’ve lived in hiding long enough, and we shouldn’t have to keep our characters hidden in fictional media.” “Nevertheless,” Lazine adds, “many [creators use queer coding] when they are either afraid or otherwise unable to confirm a character’s queerdom, often for reasons of corporate censorship. This will likely be prevalent for many more years.”

Many believe queer coded villains created negative perceptions. Plenty of villains in popular culture were queer coded by non-queer people, inadvertently amplifying queer stereotypes. Queer coding was also seen as morally depraved under the Hays Code, and with most queer coded characters being villains, this implied that they were morally depraved, as well, further contributing to stereotypes about queer people. While some believe it ramped up harmful stereotypes, others believe queer coding made way for subtle representation since it was the only type of representation available, giving queer folks characters they could identify with, even if they weren’t explicitly labeled as queer or LGBTQ+. There is a lot of queer coding that’s based on stereotypes, but there’s also queer coding that’s done tastefully and uses genuine, authentic queer experiences to create a relatable character that queer people admire.

Other Queer-Related Terms

Queerbaiting Queerbaiting is the implication of non-heterosexual relationships without delivering to gain an LGBTQ+ audience, hence the term “queerbaiting.” It’s a practice that’s often employed in pop culture. The practice of queerbaiting is often looked down upon, as it’s used to build an LGBTQ+ audience without actively depicting LGBTQ relationships and interactions.

Queer catching Similar to queer coding, queer catching is when characters are written with queer qualities but aren’t explicitly labeled as queer, at least within the work they appear in. With queer catching, the author, writer, character actor, or another person closely linked to the character is the one to confirm their queerness, typically in an interview or media appearance after the media has been released.

Pinkwashing Pinkwashing is a marketing tactic employed by businesses and corporations that involves promoting products, people, or places with queer branding to appeal to queer audiences. Pink washing is typically done to seem more progressive and tolerant without having much of anything to do with queer equality and inclusion outside of marketing.

Tokenism Tokenism is when there’s a single queer/minority character included in a piece of media to show that the group itself is diverse. It is often seen as a lazy way to seem diverse without actually representing the experiences of queers and other minority groups, as the character often speaks for the group(s) they are a part of. The term applies to all minorities, queers included.

Comments

0 comment