views

X

Research source

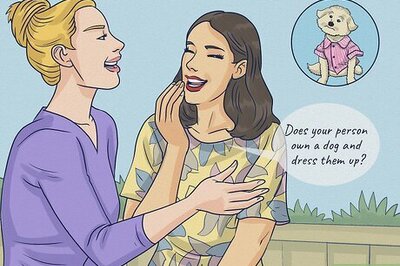

Spending time in nature can give you a sense of peace and inspire your next work of poetry.

Finding Inspiration

Read some existing nature poetry. Great writers read extensively. Reading nature poetry that's already been published by successful poets can give you ideas, inspiration, and can open your eyes to what's possible in a nature poem. A good place to find nature poetry is the Academy of American Poets website. You can search for poets, or use the website's filter to find all works categorized as nature poems. Search for poems by poets known for their nature-based works. Gary Snyder, for example, is an American poet who's been writing about nature for much of his life. Romantic poets such as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Keats are also known to include nature in their poetry. Check your library for published books of nature poetry, anthologies, and nature-themed literary journals.

Spend time in nature. If you're interested in writing a poem about nature, the best way to start is by going out into nature. Whether you go for a short walk, a long camping trip, or anything in between, getting outdoors will help you find inspiration and imagery. In contemporary times, nature takes many forms. You don't have to go out to the countryside or deep in a forest to find inspiration - try visiting an urban park if you can't get into the wilderness. Consider seeking inspiration where the natural world meets the pavement. Even remote forests wouldn't be accessible without roads to lead you there - perhaps you can find something inspiring in that transitional zone.

Write your observations. When you're out in nature (however you define it), you should begin to feel inspired or creative as you take in your surroundings. It's okay if it doesn't come to you right away - you can always analyze your thoughts/feelings later. As you observe the natural world around you, begin by noticing what you see, hear, smell, and feel. Next, try to draw associations from the things you're observing. What do your observations remind you of in your own life? Why do you notice the things you do in nature? You can take another step back and consider where you first learned to interact with nature. Don't worry about producing poetry yet. Just try to notice things in nature, write down your initial observations, and work out your own understanding of those observations.

Beginning to Write

Use your imagination. Poetry is, of course, often image-heavy. You may have a lot of image-based observations that you've written while spending time in nature, but how do you turn those into actual lines of poetry? One of the easiest ways to start is with your imagination and your initial observations. Read through the list of observations you compiled. Try to visualize different images that come to mind when you reflect on each observation. Your images don't have to be directly tied to what you've seen/heard in nature. It can be any association your mind makes. Write down a description of those images/associations.

Find a theme. Before you begin to actually compose a poem, you'll want to think about what your poem will actually be about. Obviously it will involve nature, but in what way? Why are you in nature, and what are you taking away from it? Perhaps your trip into nature allowed you to reflect on things going on in your life, or maybe you remembered going for long walks with a deceased relative when you were younger. Whatever you think your nature experience is "about," write it down and try to elaborate on it as much as possible. Theme can be thought of as a combination of an idea and an opinion on that idea. Revisit your observations, and read through the images/associations you expanded on. What about your experience stands out to you the most? What does all of it mean to you? Does being in nature make you think about life? Death? Lost loved ones? Current events, either in your own life or in politics/society/culture? Ultimately, the theme you decide on will influence not only what you write about, but how you write it as well.

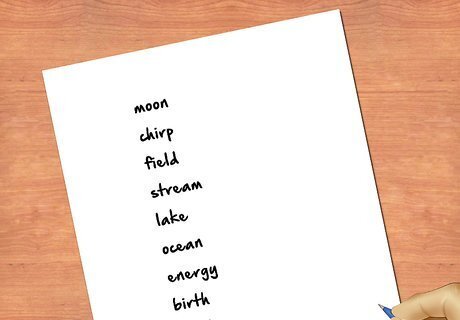

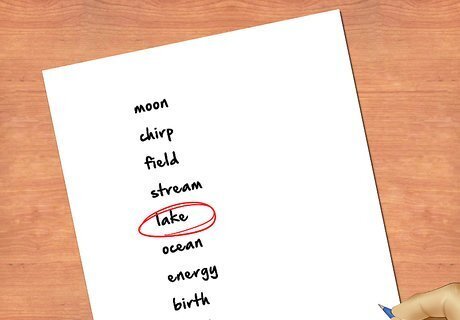

Build off of your chosen theme. Once you have your theme in mind, it may be helpful to build off of it so you have some related ideas to expand on in your poem. If nothing else, building off of your chosen theme may at least give you a bank of words/phrases to draw from that can help enrich your final piece of writing. Try making a list with three columns: sense, object, and thought. Think about what you observed in nature through the lens of your chosen theme. How do your other observations/thoughts/descriptions relate to your theme? Choose the most descriptive, the most image-filled, or the most emotionally powerful words/phrases/lines you come up with, and set them aside as possible material.

Crafting a Poem

Decide if you want your poem to rhyme or not. Poetry does not have to rhyme, but rhyming can add an almost musical quality to the words that you write. Rhyming can also help you to emphasize certain words and ideas in your poem. Think about whether or not you would like your poem to rhyme and where you might place rhyming words in your poem. Keep in mind that it is possible to rhyme too much as well, which can make a poem start to sound a bit like a nursery-rhyme. Experiment with rhyming to see what you like and remember that you can always revise to include more or less rhyming words. Rhyming can also narrow your choice of words as well. For example, it is much easier to find a rhyming word for “tree” or “flower” than to find a word that rhymes with “chlorophyll” or “chrysanthemum.” Rhymes don't necessarily have to be at the end of the line, either—they can also be internal, or in the middle of the line.

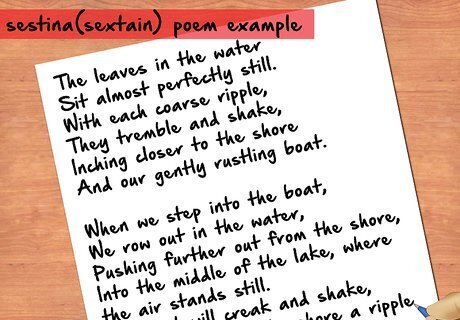

Choose a form. There are many different poetic forms. You can also choose to write in free-form, meaning there are no "rules" to follow for line length, structure, or arrangement. There is no single right or wrong way of writing a poem, and which form you choose will likely depend on your style as well as what you hope to accomplish with your poem. Some common poetic forms include: Haiku - consists of three lines. The first line contains five syllables, the second line has seven syllables, and the third has five syllables. Tanka - consists of five lines. The first three lines follow the structure of a haiku (five/seven/five), and the last two lines each have seven syllables. Lantern - a loosely-written poem meant to imitate the visual shape of a Japanese lantern. Couplet - consists of two lines that rhyme with one another. A couplet is not usually considered a poetic type, but it can be part of a poetic type. Quatrain - consists of four lines with a specific rhyme pattern. The rhyme pattern is usually one of four possible patterns: AABB (first two lines rhyme, last two lines rhyme), ABAB (first and third lines rhyme, second and fourth lines rhyme), ABBA (first and fourth lines rhyme, second and third lines rhyme), or ABCB (first three lines are all unrhymed, fourth line rhymes with the second line). Quatrains are also not poetic types, but they are often used to create a specific type of poem. Limerick - consists of five lines with an AABBA rhyme scheme. These poems are supposed to be funny (and sometimes even rude).

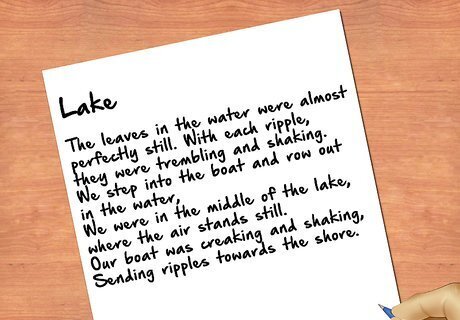

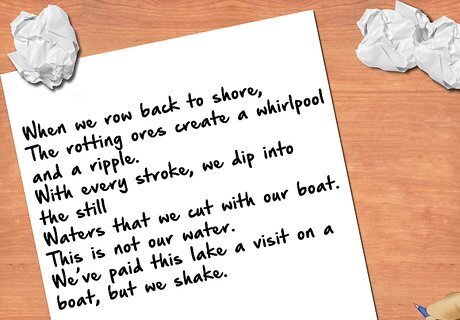

Write a rough draft. If you've chosen a form to work with, your draft should incorporate the images, descriptions, and memories you've compiled into the prescribed structure of that form. If you are writing a free-form poem, you do not have to worry about the structural "rules" of form and can experiment as you create. Choose concrete words instead of abstract ones. This will make your poem stronger and more rooted in imagery, rather than in vague concepts or ideas. Don't worry about rhyming any lines unless you've chosen to work with a poetic form that requires a rhyme scheme. Rhyming in contemporary poetry is often seen as stuffy or old fashioned, and without proper understanding of stress/emphasis a rhymed poem could be sloppy. If you're interested in working within poetic forms, try experimenting with different forms until you find one that works best for your theme and imagery.

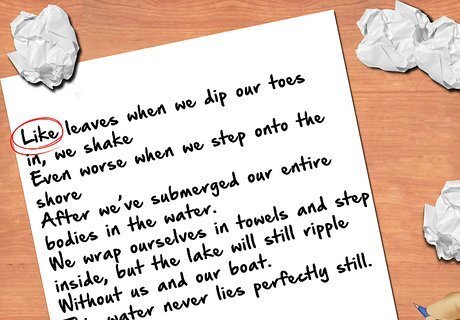

Incorporate simile and metaphor. Simile and metaphor are often what makes a poem's verses poetic. They often use concrete words to describe abstract comparisons, like saying "His eyes were an inferno" to describe someone's expression of anger. Similes are comparisons that use "like" or "as". For example, the phrase, "He's curious as a cat," uses the word "as" to compare a person's curiosity to that of a cat. Metaphors are comparisons that do not use "like" or "as", effectively pretending (for literary effect) that one thing is actually something else. For example, "Her love is a flower" compares a person's love with a beautiful but delicate flower.

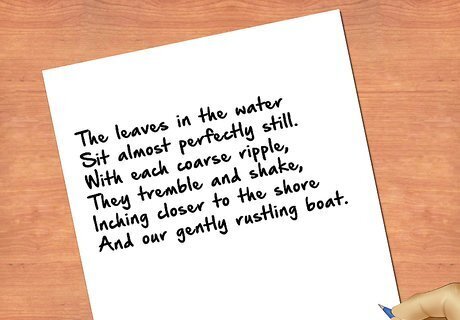

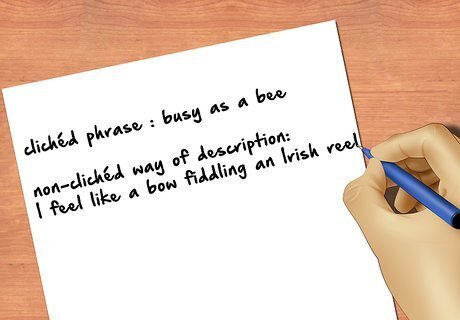

Find and improve clichés. Clichés can be thought of as dull or overused word choices and literary elements. They may have come easily as you wrote your first draft, but a cliché can quickly turn readers off to your work. Rather than saying something in a way that's tired and played out, try to come up with an original way to say what your cliché is supposed to convey. Even if it's a bit confusing or nonsensical, it will surprise and captivate a reader, rather than make readers roll their eyes. Look for any instances of cliché. Try to figure out what you were trying to say with your cliché. Describe what your cliché is trying to describe in your own original words. Re-write the cliché in a descriptive and original way.

Revise your poem. Every writer knows that revision is an important part of the writing process, and poetry is no different. Revision doesn't just mean correcting typos (although you should do that as well). Some useful strategies for revision include: cutting away prepositions, adjectives, adverbs, and any lines that explain needlessly playing with where you place line breaks (the end/beginning of a line) within your poem reading your poem out loud and thinking about the way your poem sounds (not just rhymes, if you incorporated rhyme, but also the way words sound together) rearranging lines for emphasis, sound placement, and image placement

Comments

0 comment