views

X

Trustworthy Source

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations

Specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for leading international efforts to end world hunger and improve nutrition

Go to source

There are methods to diagnose and treat bloat, some which you can do yourself, but others are best to have a bovine veterinarian to come out to help you with, especially when you have to deal with things like trocars and frick tubes. Please call a veterinarian immediately when you have an emergency.

Methods to prevent bloat involve quite a bit of management, regardless if this is feedlot or pasture bloat. These will be talked about quite a bit below.

Identifying Bloat Types

Learn about Frothy Bloat. Also known as "primary ruminal tympany," frothy bloat is primarily caused by pasture legumes (predominantly alfalfa and clovers), and other high quality forages such as young green cereal crops, canola/rapeseed, kale, turnips, and legume vegetable crops (peas, beans, chickpeas, lentils, etc.) Rapid degradation of highly digestible plant matter will cause a sudden release of cell contents that are available for microbes to digest. This sudden increase in nutrient availability causes microbial blooms, which in turn doubly increase rate of digestion. Soluble proteins and carbohydrates make up a large part of the cell contents, as do small particles which are actually parts of the plant cell walls these microbes attach themselves to. Any excess carbohydrates that microbes do not break down are stored as "slime" over their cellular bodies. This slime is highly viscous and very stable. Microbes also release a lot of gas with fermentation and digestion of these plant tissues. But with the additional build up of slime, gas is trapped in these highly stable, slimy bubbles. Rumen pressure increases the more slime and gas is produced. Just as with free-gas bloat below, the more pressure that builds up in the rumen, the more pressure is put on the lungs. If not treated promptly, the animal eventually dies of suffocation from not being able breathe. Frothy bloat is also seen in feedlot cattle that have been on a high-concentrate ration for 1 to 2 months. The cause is uncertain but it's thought that certain rumen microbes may create the stable slime, or conditions where increasing feed intake of grain is done and/or grain is fed as too fine a particulate matter; this makes conditions where there's too much concentrate and not enough roughage in the diet.

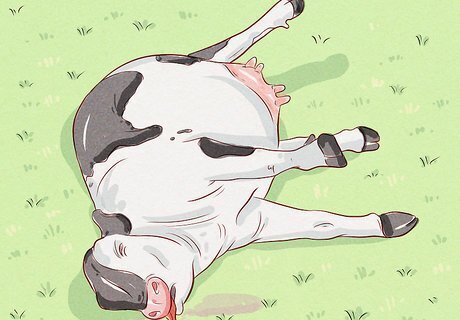

Learn about Free-Gas Bloat. This type of bloat is commonly associated with a blockage or something (like swollen lymph nodes) restricting the esophagus preventing the animal from normally burping up gases from normal process of rumination. Veterinarians call it "secondary ruminal tympany." It is also associated as a secondary issue related to an acute or clinical case of grain overload or acidosis when a drop in rumen pH causes an inflammation of the rumen and esophagus that interferes with normal eructation (burping). When cattle have an allergic reaction to a particular drug or substance, this can also cause secondary ruminal tympany if an animal experiences anaphylaxis as a result. Milk fever can also create a case of free-gas bloat. If animals are in a position where they cannot get up; like if they are laying out on their sides or have been put onto their backs for an extended time where they cannot roll over and get up (as in handling facilities, irrigation ditches, or crowded transportation vehicles), they can actually die of bloat because the rumen puts significant pressure on their lungs.

Watching for Bloat Signs and Symptoms

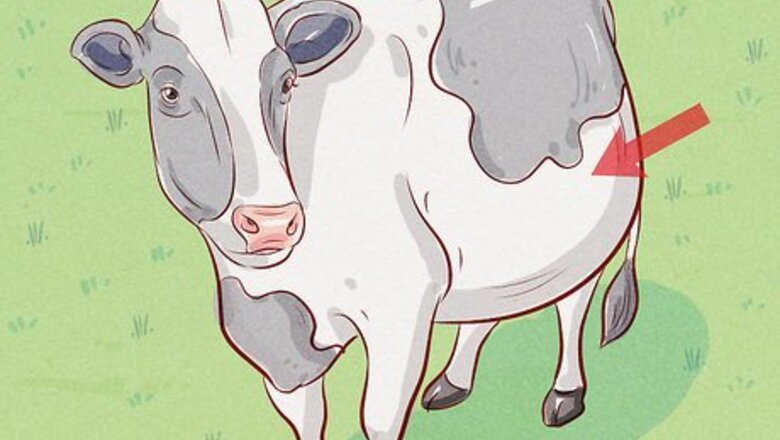

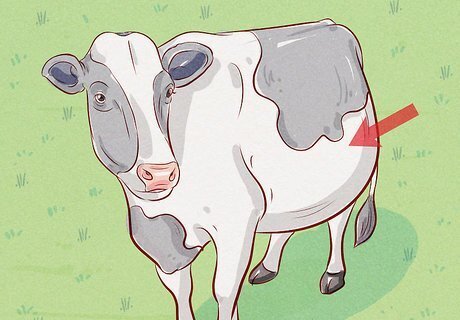

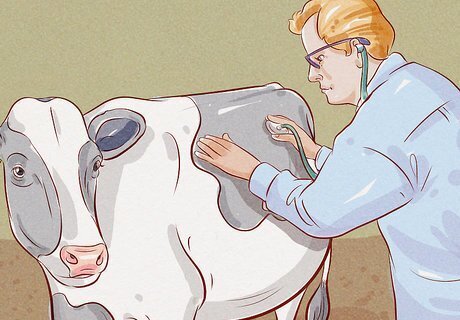

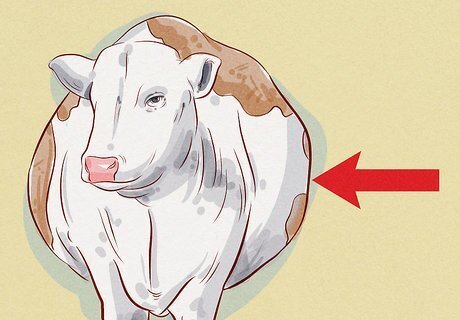

Watch for distended abdomens. The first and most important sign you need to be looking for in bloated cattle is an unusual distention of the upper left side (left flank) of the animal. The whole rumen may be enlarged resulting in a large distention of the left side. The left side is where the rumen is situated, and where you are most likely to see how much an animal is bloating.

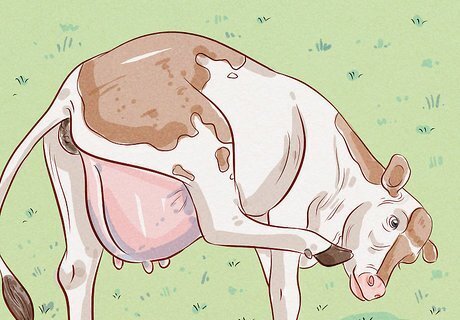

Look for signs of discomfort. Bloated cattle will often kick at their bellies with their hind legs, act restless (laying down and getting up frequently), defecate often, and even roll over as an attempt to relieve the discomfort.

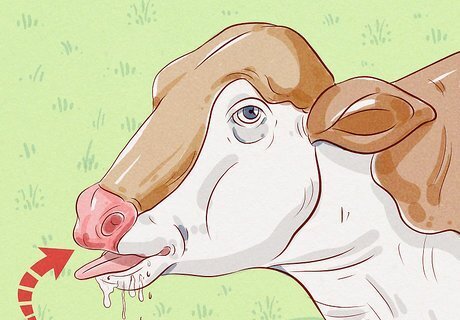

Look for difficulty breathing. Animals will try to breathe through their mouths because it becomes more difficult to breathe with the distended rumen pressing onto the lungs and diaphragm. These animals will also have excess salivation, their tongue protruding like they are panting, and head extended to get the most air into their lungs as possible.

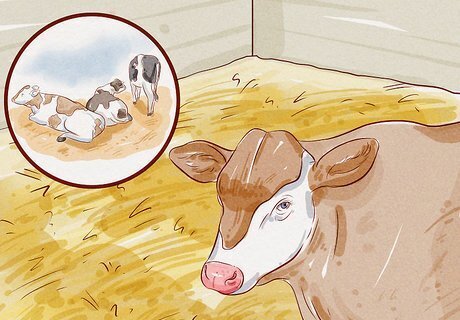

Watch for dead animals. Death can occur quickly once an animal begins bloating, but it usually doesn't occur until 2 or 4 hours after first onset. Death occurs because of the distended rumen pushing up against the diaphragm of the animal preventing inhalation. Bloat that becomes severe enough will cause an animal to collapse and die quickly, almost without struggle. Have a vet to come out to do a necropsy on your dead cattle to verify if they died of bloat. Regardless the cause of death, a bovine's rumen will swell after death because of the continued fermentation occurring well after the animal has died, resulting in a misdiagnosis without getting the vet to perform a post-mortem exam. Dead animals are more likely to occur with pastured beef cattle than dairy cattle because dairy cattle are checked more often.

Treat bloated animals (those still alive) immediately. The next section talks about how you can relieve bloat in an affected animal as quickly and efficiently as possible. Treatment does depend on how severe the animals are bloated. Mild cases just need animals to move around. But severe cases will require a visit from a veterinarian as soon as possible.

Treating Bloat

Remove all animals from the bloat-causing source immediately. All animals, not just the ones that are bloating, need to be removed so that bloating does not progress any further that it already is. Move them onto a non-legume pasture or a sacrifice lot area for the time being.

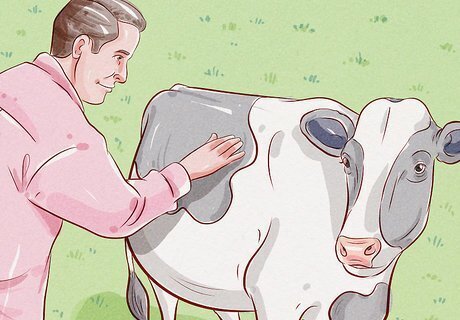

Assess the animals to see how severe bloat is. Bloat cases range from mild to severe. Mild cases show a distention of the left flank but the animal does not appear to be in distress. Moderate cases show a more obvious distention of the rumen, particularly on the left side. Animals appear uncomfortable but are not yet showing signs of laboured breathing. Severe cases show a gross distention of the abdomen, a lot of discomfort, and a protruding tongue with obvious signs of laboured breathing. If you can get the animal to where you can try tenting the skin, then note that mild and moderate bloat cases will allow you to grasp the skin and tent it. You won't be able to do so with a severe bloat case.

Call your local bovine veterinarian immediately. Tell them it's an emergency and that you need them to come out now. Or, if you can load up the affected animal[s] in a trailer to ship them to a local veterinary clinic, then do so as quickly as possible, even if it means having to load them up right in the pasture. If you have chosen and have the means to do the latter alternative, then the following steps are not necessary to follow. But, if you can't ship them to the veterinary clinic, the the next steps will be important to follow to save your animals.

Restrain the animal that needs treatment. There will be no possibility of being able to treat a bloated animal out in the field without restraining it in a working alley or holding chute so that it can't move back or forward or try to turn around. A squeeze chute is ideal, except in this instance squeezing the sides may help only if you can put the sides in so much that they're not going to put too much pressure on the animal's already painfully-distended sides. It's better if the animal is standing when things like tubing, putting in a trocar, or in worst-case scenarios, doing a rumenotomy, is needed to save these animals.

Attend to the severely bloated animals first and foremost. These animals have less time to live and deserve priority treatment to survive. Never hesitate to attend to these animals first. First thing you need to do is to try to relieve the pressure with a stomach tube. The animal may have free-gas bloat that can be easily relieved with a stomach tube. Other more invasive methods, which are more effective but traumatic, should be used only if the stomach tubing doesn't work.

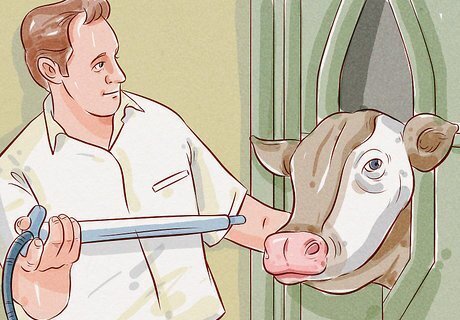

Use a stomach tube. The following steps are just like giving cattle oral medications, and should be followed in a very similar manner. Stomach tubing should also be seriously considered as a means to relieve gas pressure in the rumen on a severely-bloated case and should be first priority, because it is the least traumatic method available to save a bloated animal. It is a method most used and most recommended by the majority of cattle producers. 1) Insert the Frick tube into the animal's mouth. Go in by nudging into the corners of the mouth to get the animal to open its mouth. Don't really force the tube in, but only go in so much until the animal starts swallowing the tube. Keep going until there's only a little over 2 inches (~6 cm) of tube outside the mouth. Don't let go of the tube! The Frick speculum or metal tube (a stiff 1-1/2-inch to 1-1/4 inch PVC pipe will also work) which is ground off at the ends to prevent damage to the mouth and esophageal tissues is a 3-foot long hollow tube. It is needed to prevent the animal from chewing on and damaging the stomach tube. 2) Keeping your hand on the tube, insert the stomach tube. The stomach tube should be passed through the Frick speculum into the esophagus, where it's swallowed by the animal and goes into the rumen. You can tell you've enter the rumen by the smell coming from the tube. You will not need to put the tube in all the way, rather so that about 1 m (3 feet) is still sticking out. The stomach tube must be 6 feet (2 m) long and has an inside diameter of 1.5 to 2 cm (5/8 to 3/4 inches). If you don't have a stomach tube like that offered through veterinary supply, a 3/4 to 1-inch (2 to 2.5 cm) diameter garden hose with the metal coupling removed will work, or a 5/8 to 3/4 inch (1.5 to 2 cm) heater-hose from an auto-parts store; both with their ends ground down so that the edges are smooth. 3) Move the hose in and out to locate and free the pockets of gas in the rumen. Once the hose enters the bloated rumen the hose will become blocked with froth. You may also need to blow through the tube to free the froth from the other end. With frothy bloat and tubing it may be next to impossible to reduce the pressure. It's a different story if your animal has "free-gas bloat." With free-gas bloat, once the tube enters the rumen the gas is quickly released in less than a minute. 4) Administer an anti-foaming agent. Attach the free end of the hose to the drenching gun and pump the mineral oil-water mix (or straight mineral oil; ideal dose is 300 to 500 mL (10 to 12 oz. per dose)) into the rumen. 5) Remove the stomach tube, then the metal speculum. Release the animal when done, but keep it in an area where you can keep an eye on it for the next few hours. You may need to repeat after a few hours.

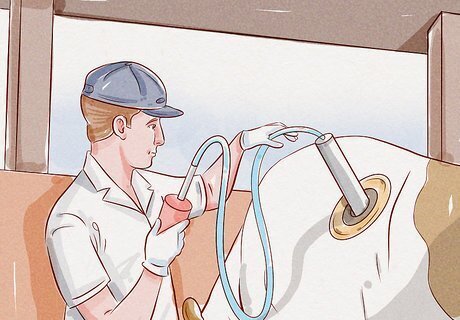

Use a trocar and cannula for situations where stomach tubing is not enough. In these situations, though the animal is showing signs of laboured breathing and quite distended, he doesn't appear close to death quite yet. Also, a trocar is necessary when a stomach tube is not enough to expel the gas in the rumen (next steps below). 1) Make a small incision into the skin in same area as the previous step. The incision should only be 1 centimetre (0.39 in) long so that the trocar and cannula can be placed into the rumen. The hole also needs to be small enough so that the cannula will stay in. 2) Insert the trocar (cannula attached) through the abdominal muscles into the rumen through the hole just made with your knife. Grasp the top of the handle of the trocar and with one move inward, punch through the abdominal muscles into the rumen. This will take a concerted effort (done right and only once) because the abdominal muscles are not soft like cookie dough. It will hurt the animal, but remember this is done not for the purpose of hurting the animal, but rather to save its life. 3) Remove the trocar and leave the cannula in the hole. Doing so allows the froth and gases to escape from the rumen. Some cannulae offered are plastic with ridges around the top so that once the rumen is punctured, the cannula is screwed into the animal so that it cannot come out. This is an advantage over the 4) Insert a piece of wire 1 foot (30 cm) to 2 feet (61 cm) long to stir the froth. The froth tends to be quite thick and heavy (or viscous) and difficult to break up, which is the reason why it's been hard for the gases to escape from the cow normally, without any human intervention. Stirring the froth will release some more gas and help break up the bubbles. 5) You may need to administer an anti-foaming agent directly into the rumen through the cannula. Use a drenching gun to do so, adding around 2 US gallons (7.57 L) directly into the rumen. Adding an anti-foaming agent will help break up the bubbles a lot quicker. 6) Leave the cannula in place for several hours, or a few days if the animal keeps having bloat issues. Check the animal and the cannula regularly for any blockage that can occur when the froth solidifies via drying when exposed to air. Check with the vet as well, as you may need to inject an antibiotic like penicillin to ward off infection. Infection is inevitable with having a cannula in the animal for several days. 7) Have the vet out to remove the cannula and suture up the damaged tissues. The trocar and cannula method may be less traumatic than a rumenotomy, but it's completely understandable if you are reluctant to do this method, even if you fully understand it means saving your bovine and not deliberately hurting it. Have a vet to come out and do this method for you. They will certainly show you what needs to be done and how to properly do it should you need to perform this procedure yourself in the future.

Perform an emergency rumenotomy if a trocar and cannula is not available, and if a stomach tube is not sufficient to relieve a very severe bloat case. When the vet is not close by and the animal is so severely bloated that you think you might lose him soon, then you will need to grab a very sharp knife and perform a rumenotomy to relieve the pressure and save the animals life. The procedure you will have to do in an emergency situation is not going to be painless for the animal, but when it comes down to needing to save his life versus causing him more pain than he is already in with a nasty, bloated stomach ache that is progressively suffocating him to death, ethics should tell you that saving his life should be of far greater priority over being scared of causing an animal pain. Do not be reluctant to have to perform the following procedure. It's a matter of life or death!! 1) Make a quick incision 6 centimetres (2.4 in) to 12 centimetres (4.7 in) long into the skin over the midpoint of the left flank. This region is also known as the hollowed triangle past the ribs and in front of the hip that can be easily found in a non-bloated bovine. 2) Continue to make the cut through the skin, through the abdominal muscles, and then into the rumen. 3) Stand aside when you cut into the rumen because there will be an explosive release of gas and rumen contents that will hit you if you are standing in the way! This will give the animal quite the relief, and allow him to breathe freely again. 4) Have the veterinarian clean the wound and do the standard surgical procedure of suturing up the rumen wall, abdominal muscles and skin to prevent peritonitis (toxic effects of stomach contents inside the body cavity). This method is quite traumatic for the animal, and even the person having to do the procedure. If in doubt, contact your local bovine veterinarian and have them walk you through the procedure, or hope the animal will live long enough for the vet to come out to do it for you.

Release the animal when you are finished. Move on to the next animal with a bloat problem. But if you only have one, that's great. Just keep an eye on this animal for the next few days to see if bloat is recurring or if anything else needs to be done. Keep your vet on speed-dial just in case anything goes wrong or if you have any questions that need answering right away.

Preventing Bloat

Never put hungry animals onto fresh legume pasture. Before you introduce animals to an alfalfa pasture, no matter the quality, make sure they are filled up on hay first (alfalfa-grass hay preferably; or have free-choice access to hay) before introducing them onto an alfalfa stand. When moving to a new pasture, move the animals when they don't appear interested in what's on the other side of the fence.

Once they're on legume pasture, keep them on there. You need to make sure your animals have a uniform and regular intake of legume forages both day and night. Do not use intermittent grazing (removing them at night and putting them back on in the morning or even mid-day) because this will encourage sudden bloat-outbreaks. Researchers studying bloat actually use intermittent grazing to encourage bloat outbreaks for their studies. Intermittent grazing causes sudden outbreaks because the animals are taken off high-quality forage for several hours and then receive a sudden influx of high-nutrients when they go back on. This sudden introduction to high nutrient forages causes bloat. It is impossible to control conditions where grazing will be interrupted by adverse weather (thunderstorms, hail, etc.), biting insects, or terrible heat waves that forces animals into the shade during the day. Animals will alter their normal grazing habits so that grazing is more shorter and intense, creating bloat issues. In these instances, animals will need to be monitored and possibly even fed hay along with their grazing so bloat issues are reduced.

Use management-intensive grazing to reduce length of grazing period cattle are on a paddock or pasture. If livestock where put onto a legume pasture where they could select-graze what plants they wanted to eat, bloat problems could arise. Situations where animals have not yet acquired a taste for alfalfa and are continuously grazed will select first mostly grasses and other plants and try to avoid most alfalfa. When these plants have been depleted, they will then target the alfalfa, and as a result will bloat. This can happen a few days to a week or so after being introduced onto a legume-mix pasture. With rotational or management-intensive grazing, livestock are managed so that they will graze a paddock every one to 3 days. This discourages selective grazing by the animals, and encourages leaving behind plant residue, especially when a "take-half-leave-half" system is used. It's important to move cattle to a fresh paddock when they are not hungry, or do not appear interested in moving to a new forage stand. Doing so encourages plant residue to be left behind after each move. You can never really have too much residue left behind after grazing, because it's better to have "lots" behind that could be grazed more, than to move them when there's almost nothing left, and as a result they're quite hungry for the next paddock.

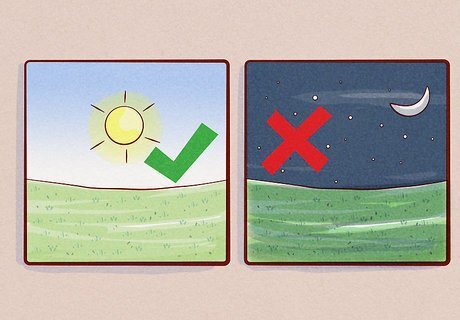

Move animals to a new pasture or paddock in late afternoon, never in the morning. Cattle tend to eat more in the morning than the afternoon, and heavy dew in the morning also increases rate of digestibility, which increases the likelihood for bloat.

Defer grazing until legume plants are fully grown or in full-bloom. Pre-bloom or vegetative alfalfa and clover are a significantly higher risk for bloat than more mature plants. If you take a piece of stem and leaf in your hand of immature alfalfa and roll them into a ball, then squeeze, you will find that a lot of juice and froth will come out. This is a sign that it is very highly digestible. Plants that are in full bloom are higher in fibre and less digestible, thus lower risk for bloat.

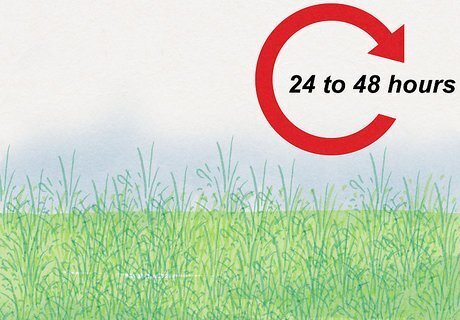

Graze pastures that have been swathed and wilted down for 24 to 48 hours This wilting reduces moisture content of the swathed plants (via evaporation and transpiration). Lower moisture reduces bloat incidence.

Use an anti-foaming agent when grazing cattle on high-legume pastures. Check with your local veterinarian or livestock-farm supply store for an anti-foaming agent that can be given to cattle. Bloat Guard is one product that may be readily available. The detergent "poloxalene", the active ingredient in Bloat Guard, has been found to be very effective at controlling bloat. (It's not guaranteed to prevent bloat when offered free-choice when mixed with grain because of variable intake levels and time period between visits.) Alfasure is another product offered via prescription from your vet that is effective at bloat-control. Free-choice trace mineral salt may also help reduce bloat incidences.

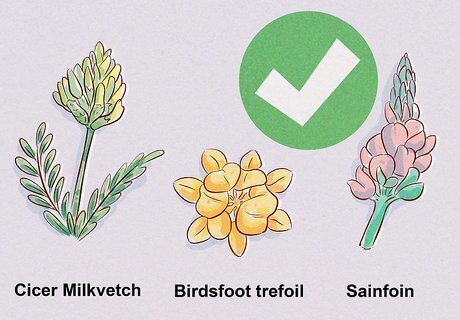

Establish bloat-safe legumes into an existing pasture or when seeding down a new pasture. Bloat-safe legumes include cicer milkvetch, birdsfoot trefoil, sainfoin, and fenugreek. While these legumes are harder to establish than alfalfa or clover, once established they can be managed so that they help with reducing or eliminating bloat altogether in your animals. For example, a stand that is at least 60% legume and 40% grass with the legume component made up of 25 to 30% sainfoin in an alfalfa-sainfoin legume mix will be enough to reduce bloat by as much as 98%. Sainfoin has condensed tannins that bind to proteins in the rumen and prevent their degradation by rumen microbes. A legume stand made up predominantly of non-bloating legumes will also work well.

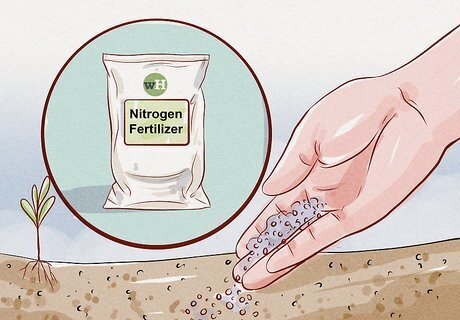

Improve production practices so that you increase the amount of grass in with alfalfa or clover stands. You may have a stand that is predominantly clover and alfalfa and want to increase the amount of grass in there. Options to do so is to apply nitrogen fertilizer, seed grass into the existing stand, or heavy-graze the legumes. Nitrogen fertilizer will encourage grasses to outcompete the legumes, and cause the legume nodules to be "lazy" and fix less nitrogen as a result. Seed down grasses when stand has been grazed heavily or cut low, and harrow after to encourage seed-to-soil contact. Adding nitrogen to the stand will encourage existing grasses to also grow. Auto-toxicity from existing alfalfa plants will not affect the germinating grasses. Heavy grazing will negatively affect the alfalfa plants. Impact to the roots and not allowing plants to reseed themselves can reduce alfalfa stands in the pasture, but increase grass. Be careful about overgrazing, though.

Prevent feedlot frothy bloat by feeding more roughage and less fine grains. Feedlot finisher rations should include at least 10 to 15% roughage. Grains should never be finely ground to where it is good for pig or chicken feed, instead they should be rolled or cracked.

Cull cattle in breeding herds if they are prone to bloating. Current studies have shown that bloating is heritable, can can be reduced in a breeding herd by culling out those animals that have bloated, if natural occurrences haven't taken care of some of those animals for you (i.e., animals die of bloat). Culling is less possible if you have a herd were culling is not an option, such as if you are custom-grazing or -feeding cattle. Careful management needs to be implemented to reduce risk of bloat in cattle. See the bulleted tips above.

Comments

0 comment