views

- Identify 3 to 7 learning outcomes students will demonstrate after completing your course and develop a syllabus with the schedule, materials, and assignments.

- Start your proposal by explaining how your course fulfills the university’s needs and goals and what students will learn that they wouldn’t otherwise.

- Describe what gap your course fills within the department or university’s curriculum and highlight your expertise to show that you can teach it.

Find the right university for your course.

Identify a university that matches your course content. If you’re an experienced professor, find a university that aligns with your expertise and the content of your course. Research the university’s mission and values and what courses they already offer. Knowing your audience can help you tailor your pitch to match their specific needs and interests. If your course is on aircraft mechanics, reach out to a trade school. If it’s a creative writing course, reach out to a community college or a small private college. To propose a new graduate-level major or program, contact the dean or assistant dean for Academic Affairs at the appropriate college. If you’re a professional looking to pitch a course, contact the head of whatever department your course fits under to see if they can pitch your idea.

Define the target audience of your course.

Identify which students are going to take the course. The course you propose should have the potential to attract a certain number of students. Define what major or student group would benefit from this course. Should this course be for undergraduate, graduate, or professional-level students? Would there have to be any prerequisites, corequisites, or qualifications required for a student to join the class and understand the content? These questions can help you meet the needs of students and make sure your course fits into the university’s academic framework.

Describe the learning outcomes of the course.

Explain 3 to 7 things the students in your course will learn. Begin each outcome with a measurable action verb, like label or summarize. Then describe the knowledge and abilities that students will be able to demonstrate after learning the course content. One learning outcome might say, “Identify and summarize the major events of the French Revolution and how each impacted the revolution’s outcome.” Another might say, “Apply important chemical concepts and principles to write a chemical reaction research paper.” Use action verbs from Bloom’s Taxonomy, an instructional framework that’s been used by teachers and professors for generations to create an organized list of objectives for their courses. Words from Bloom’s Taxonomy include “remember,” “understand,” “apply,” “analyze,” “evaluate,” “create,” “define,” “classify,” or “identify.”

Identify the resources and materials for the course.

Collect videos, books, and readings that support your learning outcomes. Collect the resources you already have that can help support students’ learning. Make a list of the resources you need to find and search for them at your local library or online. Collaborate with a peer or with other visiting teachers or professors to find materials you can use in your course. Include supplemental materials (like lab manuals or books on a specific topic) in addition to your day-to-day materials to help students understand the concepts better. If your course includes a lot of practical learning (like dissections or fieldwork), you might have a guest speaker or hand out datasets for students to analyze.

Develop your course syllabus.

Create a syllabus that outlines the course assignments and timeline. Write the title of the course, the course number, the time and date of the class, and how many credit hours the class counts for at the top. In your syllabus, include a course description, the learning outcomes, the university’s academic policies, your grading criteria, and a full schedule with all the assignments and readings. Include homework submission guidelines, policies for late work, expectations for attendance and participation, what technologies students can use, and policies on student collaboration. A syllabus not only communicates your expectations for the students and describes what they can do to be successful, but it’s a permanent record of the class for the university.

Prepare a presentation if necessary.

Create a presentation to persuade the university to adopt the course. If the university requires it, you might need to prepare a visual presentation. Begin the presentation with an attention-grabber, like a question, an anecdote, or a statistic. Follow up with a statement that tells the audience what your presentation is about. If your course is on world history, you might use an attention-grabber like, “History majors make up roughly 7.9% of all university degrees” or “What would a world without history look like?” Try to develop 3 main points with statistics, demonstrations, and personal experiences. If you’re creating a course on accounting, you might talk about your experience in the financial field and the career outlook for accountants. At the end, sum up your main points in 1 sentence and leave the audience with a call to action or thought-provoking statement. If you’re creating a course on personal finances, you might say “I urge you to help create the next generation of financially literate adults, not only for their futures, but for ours. Thank you.” Use visual aids, like slides or handouts, to illustrate key points and engage the audience. Come up with questions and counterarguments the audience might have after the presentation and prepare a few well-thought-out responses.

Talk about the gap your course fills in the curriculum.

Describe what instructional needs are filled by your course. State the problem your course aims to solve. Address how your course fills the university’s needs and academic goals, how it relates to other courses within the same discipline or track, and what it will provide students with that they wouldn’t get otherwise. In addition, describe how your course is different (in its content and its goals) from other courses the university already offers.

Highlight your expertise in your proposal.

Reference your educational qualifications and professional experience. If you aren’t an established professor or if the university isn’t familiar with you, describe any relevant achievements you may have and any research you may have published. Develop an elevator pitch to persuade the university that you can deliver high-quality teaching and mentorship. Limit your elevator pitch to 30 to 60 seconds. Explain who you are, what qualifications and skills you have, and what your goal is in speaking or writing to the university. “My name is Sydney, and I have over a decade’s worth of experience in accounting with small and mid-sized firms. I’d love to teach a course at your prestigious university and share my experience with aspiring accountants.” Share examples of successful projects, case studies, or any previous jobs that show the practical applications of your course. “As a programmer, I’ve worked with several large businesses, including Google and IBM. I’ve led hundreds of successful projects and would love to share my knowledge with students.” If you’re a professor who is new to the university, submit a curriculum vitae, or a complete resume with all your academic accomplishments, along with your proposal.

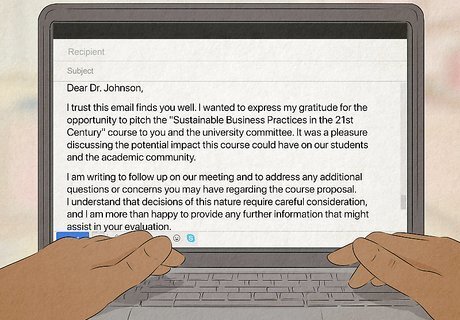

Ask about the next steps in the process.

Follow up with the university’s representatives after your pitch. Either in person or over email, remind the representative of the context where you met, thank them for allowing you to present and ask them about the next steps in the process. If necessary, address any concerns that were raised during your presentation or in your proposal. This can show the representatives that you’re willing to tailor the course to meet the university’s requirements. Be open to any feedback you might get and revise your syllabus with any advice that the university representatives give you.

Comments

0 comment