views

Brainstorming

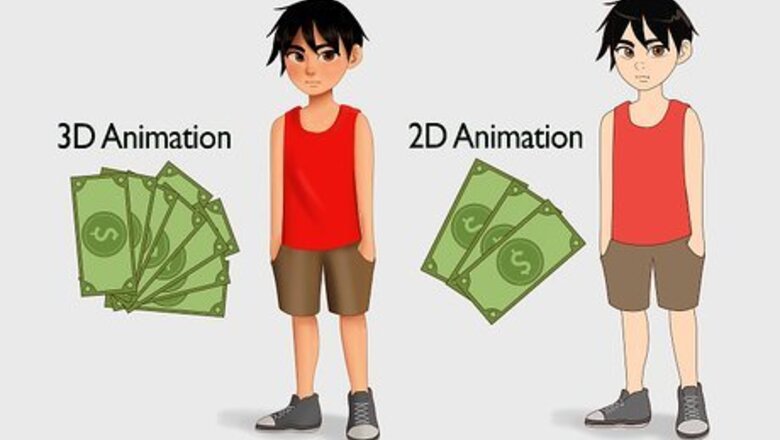

Consider your resources. Your budget might be high, but chances are, your imagination and your talent are not. When brainstorming a new idea for a cartoon, keep in mind how much you can afford to invest in the process and what your artistic skill is capable of producing. If you are a beginner, you might want to stay away from stories and themes that require animating complex scenes, like huge battles or intricate machinery. Your animating skills may need to be refined and practiced more before you are ready to tackle a project of that size. Also keep in mind that you will need more equipment depending on how complex you want your cartoon to be. A claymation cartoon with two dozen characters and four sets will require more supplies than a cel animation with only one scene. If budget is an issue, keep it short and simple.

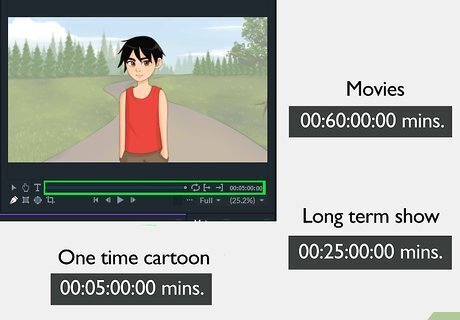

Think about length. The right length for your cartoon will vary based on the market you are trying to distribute it in. Knowing the length from the start will help you brainstorm a story that can fit within that time frame. Most cartoon shows are 10-15 minutes long, with commercials. Cartoon movies can go anywhere from 60 minutes to 120 minutes. If a one-time cartoon made for the Internet is all you want to create, you can create a short running from 1 to 5 minutes. Creating anything longer may turn people away from viewing it.

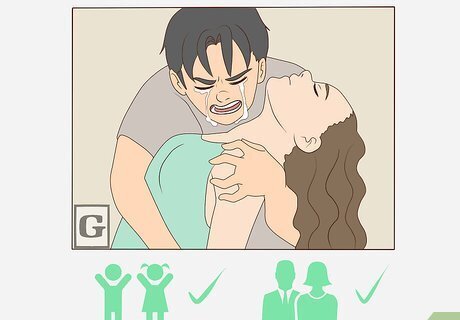

Know your intended audience. Even though cartoons are traditionally aimed at kids, there are many cartoons made for older adolescents and adults. The age group and other audience demographics should shape the ideas you come up with. For example, a cartoon about something tragic, like the death of a loved one, would be better reserved for a slightly older audience. If a young audience is your target, you would be better off choosing a topic that is a little simpler to understand and more concrete.

Work from your experiences. Another way to put this would be, “write what you know.” Many storytellers write stories based on events, feelings, or relationships they experienced in their own lives. Make a list of possible life events you have been through that could be the underlying idea behind a cartoon. If you want to create a cartoon with a serious tone, think about life experiences that really mold and shape you: an unrequited love, the loss of a friend, working hard toward a goal that seemed impossible, etc. If you want to create something more humorous, take an everyday situation like waiting in traffic or waiting on an email and exaggerate how difficult the situation is in a funny way. Alternatively, you can use something already funny to create a humorous cartoon.

Use your imagination. Of course, there are many plots that do not involve any trace of life experience. You can use your interests and your imagination to craft an entirely new premise, as long as you include enough relatable details to help people connect to the characters or the story. Relatable details include underlying themes that are universally appealing. For example, most people can relate to a coming-of-age story, regardless of whether that story takes place in the contemporary real world, in a futuristic space-age setting, or in a sword-and-sorcery fantasy setting.

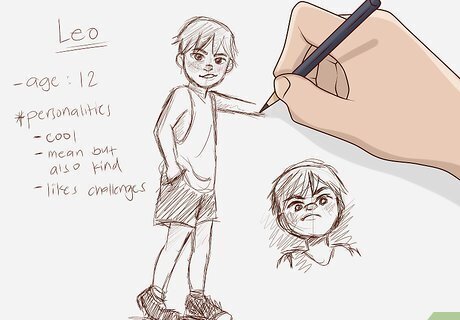

Design an appealing protagonist. Make a list of character traits you would like to see in a protagonist. Write positive features as well as faults to avoid making a character too perfect. This is an important step no matter how simple or complex your cartoon will be. While a character in a longer, more serious cartoon will need to develop more, a short, funny cartoon will need a protagonist with a clear goal and clear character traits that allow him or her to react to the conflict in whatever way he or she does.

Scriptwriting and Storyboarding

Write a script if there is any dialog. If any of the characters in your cartoon will have spoken lines, you will need a voice actor to recite those lines, and your voice actor will need a written script so that he or she knows what needs to be said. You need to know the script before you can animate the cartoon. The mouth moves in different ways for different phonemes, and you will need to animate these different mouth movements in a believable way so that any voice overs you add later will match them.

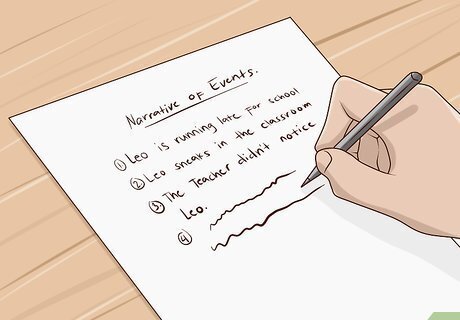

Jot down a basic narrative of events. If there is no dialog in the cartoon, you might be able to skip a formal script. You should still write down a basic narrative of events so that you can keep track of the story and its different pieces, though. Write down what happens, with who, and where. Write multiple drafts of any script before beginning the production phase. Write your first draft, set it aside, and come back to it in a day or two to see how you can improve upon it and make it flow more effectively.

Divide your story into main parts. A short cartoon may only consist of a single scene, but if your cartoon is a little longer, you might need to divide it into multiple scenes or acts for easier management.

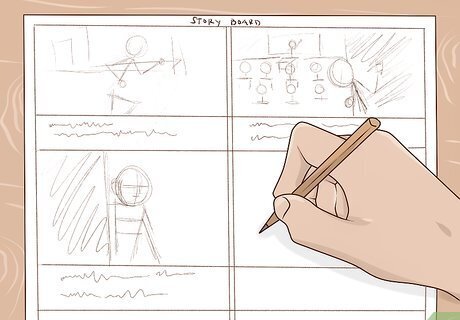

Sketch out each major change in action. When you sketch out a formal storyboard, each major change in action should be shown in one of the storyboard squares. Minor changes should be described, but may not need to be drawn out. Use basic shapes, stick figures, and simple backgrounds. A storyboard should be fairly basic. Consider drawing your storyboard frames on index cards so that you can rearrange them and move parts of the story around as necessary. You can also include notes about what is happening in each frame so that it will be easier to remember later on.

Animating

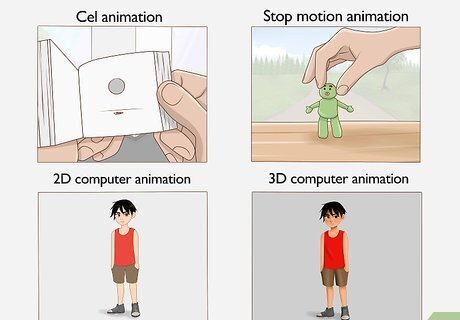

Familiarize yourself with the different types of animation. In general, most forms of animation will fall under the categories of cel animation, stop motion animation, 2D computer animation, and 3D computer animation.

Try your hand at cel animation. Cel animation is the traditional method of making a cartoon. You will need to hand draw each cel or sheet of animation and take pictures of those cels with a special camera. Cel animation utilizes a principle similar to the way a flipbook works. A series of drawings is produced, and each image varies slightly from the next. When displayed in rapid succession, the differences create the illusion of movement. Each image is drawn and colored on a transparent sheet known as a "cell." Use your camera to photograph these drawings and edit them together using animation editing software.

Use stop motion techniques. Stop motion is another traditional form of animation, but it is used less commonly than cel animation. “Claymation” is the most common form of stop motion animation, but there are other puppets you can use and make for this sort of cartoon, as well. You can use shadow puppets, sand art, paper puppets, or anything else that can be moved into a range of positions. Each movement must be small. Take a photograph of each movement after making it. Edit the photographs together so that they are displayed in rapid succession. When viewed in this manner, the eye will perceive movement.

Consider 2D computer animation. You will need a special computer program for this type of animation, and the product will likely look like a smoother version of a cartoon animated with cel animation. Each 2D computer animation program will work differently, so you will need to find tutorials for the specific program you intend to use in order to learn how to do it. A common example of 2D animation is any cartoon created using Adobe Flash.

Animate in 3D using computers. As with 2D animation, you will need special software to produce 3D animated cartoons, as well. In some sense, 3D computer animation is similar in style to stop-motion animation, but the graphics can range from seeming very blocky and pixelated to being very life-like. As with 2D computer animation, each animation software works a little differently than the others. Examples include Maya and 3D Studio Max.

Sound Effects

Get the right equipment. You will need a good microphone and a way to prevent echo or background noise from bleeding into the sound you want to keep. A high-quality computer microphone will work effectively enough for a beginning cartoon, but if you plan to seriously market and distribute your cartoon, you will eventually need to invest in more professional equipment. When working with a small microphone, encase it in a tube speaker box lined with foam to cut out echo and excess background noise.

Record your own sound effects. Get creative and look for simple, everyday ways to make noises passably similar to the noises you need for your cartoon. Make a list of sound effects you will need. Be creative and thorough, including everything from the obvious (explosions, alarm clocks) to the less obvious (footsteps, background noise). Record different versions of each sound so that you have more options to use. A few examples of sounds you can create include: Fire - Manipulate a piece of stiff cellophane Slap - Clap your hands together once Thunder - Shake a piece of plexi-glass or thick cardstock Boiling water - Blow air into a glass of water using a straw Baseball bat hitting a ball - Snap a wooden matchstick

Look for free pre-recorded sound effects. If you do not have access to the equipment or otherwise find it impossible to make your own, there are CD-ROMS and websites offering royalty-free pre-record sounds you can use as desired, and this might be a more viable option for you. Always review the usage permissions for any pre-recorded sound effects you use. Even if something is free to download, it may not be free to use, especially for commercial purposes. It is very important that you know what you are permitted to do before you use a sound for your cartoon.

Record real voices, if necessary. If your cartoon has dialog in it, you or others you know will need to be the voice bringing your characters to life. As you record your lines, read from the script using appropriate intonation and expression, and make sure that you match your lips to the animated lips of the cartoon. Consider manipulating the voices using computer software. If you have fewer voice actors than characters, you can change the voice of one character simply by adjusting the attributes of the voice sample you already gathered. You will need to invest in special audio editing software to do this, but depending on which one you use, you can likely change the pitch and add overtones, like metallic garbles, to the voice recording.

Distribution

Distribute the cartoon using your own resources. If you have a short, one-time cartoon, or if you are trying to gain a name for yourself on your own, you can add your new cartoon to your digital portfolio and upload a copy to a personal blog, social media account, or video website.

Network with people in the industry. Networking is a really important part of the filmmaking process. Meet others who work in film, production, etc. as well as agents in the business. Be kind and polite to everyone you meet and work on building relationships with them so you have contacts in the industry. That will help you market and sell your cartoon.

Approach a distribution company, animation company, or TV station. If you created a pilot episode for a cartoon at home, you can spread word for it through either route. If accepted, you will need to figure out your new production schedule for future cartoons so that you can get to work all over again. A distribution company will review your pilot episode and determine how marketable it might be. If they decide to represent your cartoon, you will be given a distribution plan and revenue projection. Ask for a formal letter of interest at this point and show the letter to potential investors to let them know that a distributor will be willing to represent your cartoon. If you go directly to an animation company or TV station with your pilot episode, they might be willing to accept and distribute it directly, especially if they have empty time slots to fill.

Comments

0 comment