views

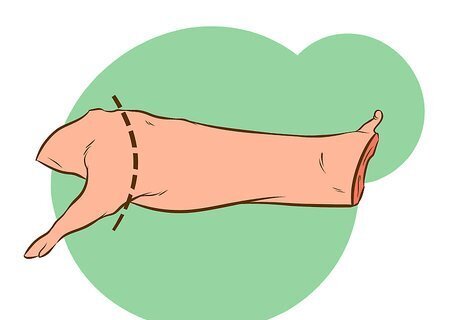

Preparing the Pig

Get the proper equipment. While the process itself is straightforward, breaking down a hog is a big job–the average 250 lb. hog yields about 144 lb. of retail-ready cuts of meat. That's a lot of valuable pork to mishandle, so it's important that you take the time to get the equipment to do things properly, reducing any possibility of waste and spoilage. We're not talking about a jackrabbit, here. To process a hog, you'll need: Sharp stainless knives, at least six inches long 1234931 1b1.jpg A meat gambrel and winch, available at many outdoors and sporting goods stores 1234931 1b2.jpg Sawzall or hacksaw, used to separate the ribs 1234931 1b3.jpg A large tub or barrel with water, large enough to submerge the hog into, along with a heat source large enough to heat the water to boiling 1234931 1b4.jpg A bucket 1234931 1b5.jpg A large, flat surface outdoors, about waist-high–some wood planks on sawhorses make a good makeshift surface 1234931 1b6.jpg A meat grinder for processing ground pork (optional) 1234931 1b7.jpg

Select the right pig. The ideal hog for harvesting is a young male that's been castrated before reaching sexual maturity, called a barrow, or a young female, called a gilt. Generally, hogs are slaughtered in the late fall when temperatures start to cool, at which point the hogs are ideally between 8 and 10 months old and between 180 and 250 lbs. Withhold all food for 24 hours prior to harvesting so the animal's intestinal tract will be clean. Supply plenty of fresh, clean water for the animal to drink. Old, intact males are called boars, and will have a distinctively funky taste, the result of scent-gland hormones, while sows–old females–have a similar note of funk in the flavor. If you're processing a wild boar, you need to remove the genitals and the scent gland near the hind quarters immediately to avoid subsequent “taint.” Some hunters will trim off a bit of fat and fry it up to check for a funky smell before going to all the work of dressing out the hog, or you can just go ahead and process it anyway, because some people don't mind the flavor.

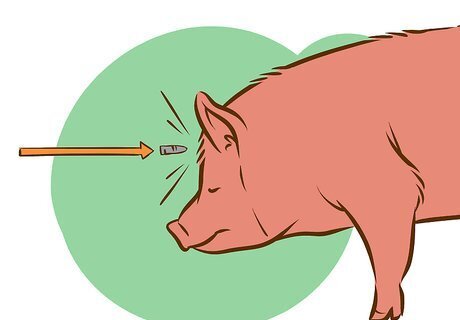

Humanely kill the pig. Whether you're harvesting a farm-raised hog or hunting one in the wild, you need to make sure you start the process as clean as possible by using a quick kill, immediately draining the blood afterward to improve the flavor of the meat. The issue of killing the hogs by draining them is a common debate. The morally preferred method of killing hogs is to use at least a .22 caliber rifle shot through the brain to kill the pig quickly and painlessly. Draw an imaginary line from the base of each ear to the opposite eye and aim for the intersection of those two points. Pigs' brains are extremely small, making the need for an accurate shot essential. Traditionally, many butchers preferred killing hogs by bleeding them out after first stunning them with a hammer, because shooting them is so tricky. A common belief is that, if the vein is cut while the animal is still living, the blood drains more thoroughly and the meat is eventually tastier. In many commercial slaughterhouses, hogs are stunned electrically and then killed by cutting the jugular vein. For some, however, this is unusually cruel. In the United States, the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act of 1978 (HMSA) prohibits the inhumane slaughter of livestock, such as pigs, intended for commercial purposes. Technically, this only applies to hogs slaughtered in USDA-approved facilities, not private property. However, some states have issued rulings that livestock can only be processed in those facilities, making it important that you research the state bylaws that govern livestock.

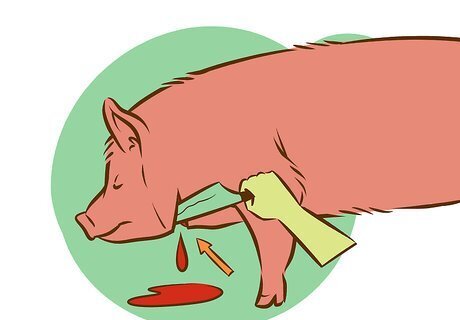

Cut the pig's throat. After you've killed or stunned the pig with a shot, feel for the pig's breastbone, and insert your knife a few inches above it, making an incision across the front of the throat, at least, 2–4 inches (5.1–10.2 cm) long. Insert the knife into your incision, and push it about 6 inches (15.2 cm) upward, at a 45-degree angle toward the tail. Twist the knife and pull it out. This is the quickest way to "stick" the pig. The blood should begin draining immediately. Some people struggle to find the exact spot necessary to stick the pick quickly. If you're unsure about whether or not you've got it, all you need to sever is the jugular vein. Some will just cut deep across the throat, just under the jawline, all the way to the spine. You'll know when you've hit it by the volume of blood that comes out. Be extremely careful when you move it to bleed the pig if it's still thrashing. If you've just stunned it with a shot, you may need to cut the throat before you get a chance to hang it. Use extreme caution. It may still be thrashing involuntarily, making it dangerous to move in with a very sharp knife. Shift the pig onto its back and hold the front legs in place with your hands, letting a partner use the knife.

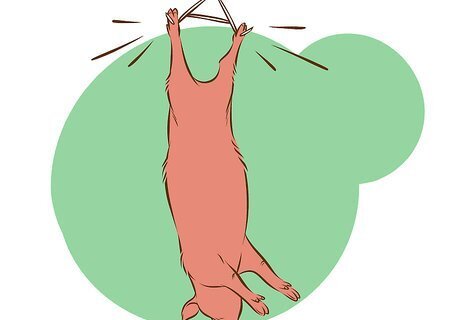

Hang the hog. After killing or stunning the hog, you need to hang it, preferably using a meat gambrel, which is like a big clothes hanger made for hanging meat. Hook a chain onto the gambrel and attach it to a winch, or the back of a truck if you want. Start by sliding the hooks at the bottom of the gambrel through the hog's heels, piercing them deep enough to support the weight of the entire hog. Then use a winch (or elbow grease) to raise the hog up and allow gravity to do the work of draining it. This needs to be done as soon as possible after the animal has been killed. A pig will take about 15-20 minutes to bleed out. If you don't have a gambrel, you could also make a small incision behind the back leg tendons in the hog and insert a wooden dowel, or a length of pipe as a substitute. You can hook a length of chain onto the end and bootleg yourself a gambrel. Barn rafters make perfect places from which to hang the hog, as well as low-hanging sturdy tree limbs. Find a suitable location, preferably as close as possible to the killing spot, before you've got 250 lb. of dead weight on your hands. If necessary, gather the hog into a wheelbarrow to move it to the draining location. Use a clean, sterile bucket to catch the blood, if you want. Put the pig's entire head into the bucket to make sure you catch everything. Pork blood makes excellent sausage and is an actively sought-after ingredient in cooking.

Scald the skin in hot water, if you want to keep it. Many butchers will probably want to retain the skin, which includes the bacon, the belly fat, and the cracklings, making it useful, delicious, and slightly more labor intensive than if you just want to skin the hog. If you do, the best way to remove the hair is by dunking the hog several times into scalding water and scraping the skin thoroughly to remove it. The best way to heat the water is usually the most rustic: start a fire in a safe fire pit and settle the basin into it, or on top of a sturdy grate. It doesn't need to boil, but it should be at least 150 F. Make sure it is absolutely secure. Keeping the hog on the gambrel, dip it gently into the simmering water, no more than 15 or 30 seconds, and then remove it. If you don't have an outdoor vat big enough to soak a whole hog in, some people have had success soaking a burlap sack in hot water and wrapping the hog in it for several minutes to soften the hairs and move in with the scraper. Wild boars with super-thick coats will likely need to be trimmed with clippers or shears before being dipped like a domestic pig, whose fur is usually somewhat finer.

Scrape the hair off using a sharp knife. After dipping the hog, place it on a flat work surface and get to work. A couple of sawhorses with plywood boards and a tarp can work perfectly in a pinch, as well as a picnic table, if you've got one. You want the hog about waist high. A sharp knife works extremely well in scraping the fine hairs off the skin. Start with the belly-side up, placing the knife blade perpendicular to the hog and scraping toward your body in long, smooth strokes. This may take a while and involve several dippings to get all the hair off completely. Some people like to go back and use a small torch to singe off the remaining hair, if necessary. Hog scrapers or bell scrapers used to be commonly used in processing hogs, but are increasingly difficult to find. Lots of people will go to the torch more quickly, as it's very effective at getting the little, hard-to-find hairs off the skin.

Skin the hog if you don't want to remove the hair. If you don't have a vat big enough to scald the hog in, or just don't want to put in the effort, it's perfectly fine to go forward with skinning it and discarding the skin. Skip forward to the following method to remove the entrails, then work your knife around the hams to start stripping the skin. To remove the skin, pull the skin back and work a very sharp boning knife underneath, working your way down slowly and trying to retain as much of the fat as possible. Skinning a hog should take anywhere between 30 minutes and an hour.

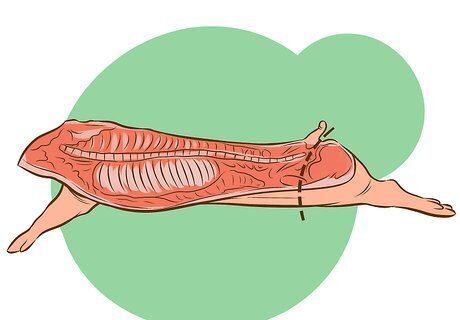

Removing the Organs

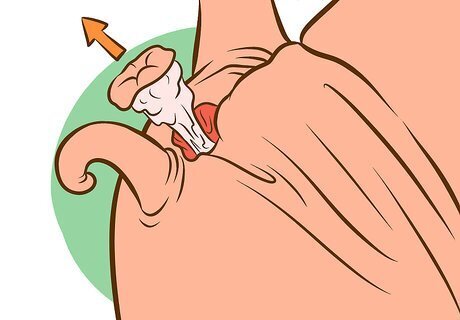

Cut around the anus and pull it upward. To start removing the entrails, work a smaller knife around the anus (and the vaginal opening) of the hog, about an inch or two deep. Make the circle about two inches wider than the anus itself so you don't pierce the colon. Grab ahold and pull up gently, then use a rubber band or a zip-tie to pinch it off. This closes everything up, so you'll be able to pull it out the other side, when you open up the chest. Some butchers wait to remove these organs until after removing the offal and the intestines, but it's good to take precautions, because these are the bacteria-laden parts of the animal that can contaminate the meat. Remove the testicles of intact boars, if you haven't already. Wrap a rubber band around them to gather the testicles and sever them. It's better to do this as soon as possible after killing the animal. To remove the penis, pull it away from the animal, and work your knife underneath it, slicing along the muscle that works back toward the tail. Pull it lose and discard.

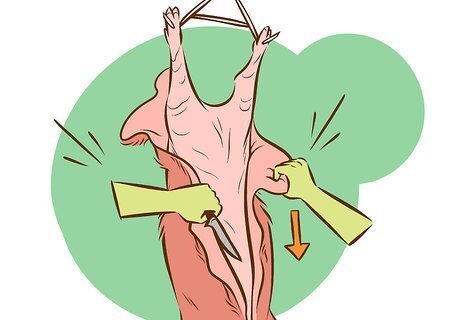

Cut from the sternum to the groin. Pinch the skin near the base of the sternum, where the ribs end and the abdomen begins, and pull toward you as far as possible. Insert your knife and gently work your way down the center line of the pig's belly, in between the two rows of nipples. Be extremely careful not to puncture the stomach lining and the intestines. Keep working your knife until you get all the way up between the animal's legs. At some point in this process, gravity will likely work in your favor and the entrails will start falling out without you having to do much. As soon as you start opening the belly up, it's a good idea to have a big bucket or tray ready to catch the organs. They'll be heavy, and it's important that you handle them delicately.

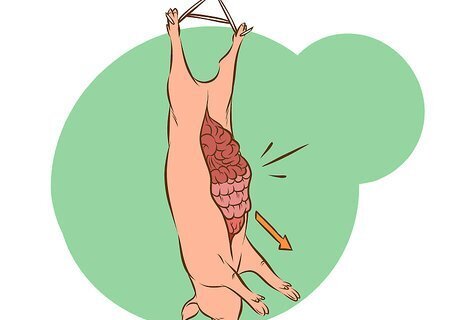

Reach into the cavity near the groin and pull downward. Everything in the digestive tract should fall out relatively easily with a bit of coaxing, including the lower intestine that you tied off earlier. Use you knife to trim away any stubborn connective tissue. The kidneys and the pancreas are perfectly edible and popular items to reserve. Some serious do-it-yourselfers will save the intestines to process into sausage casings, though this is a time-intensive and difficult process. Adipose tissue is a layer of fat found near the pig's kidneys, and is popular to reserve for rendering into lard. You don't need to remove it now, but be gentle with the cavity as you work the organs out and into the bucket. It can be harvested by "fisting out" the tissue, essentially by pulling it free with your hands.

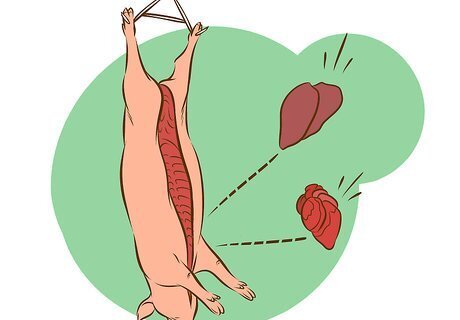

Separate the ribs in the front by splitting the breastbone. After the entrails are removed, you need to open up the chest to remove the rest of the organs. You can use your knife to separate the front of the rib cage, working your way in between the layer of cartilage that connects the breastbone. You shouldn't have to use the saw to do this. After separating the ribs, remove the rest of the organs. The heart and liver and commonly reserved and eaten. Some people will start by reinserting the knife into the "stick" puncture made earlier and cut toward the tail, while others find it easier to start nearer the stomach and work toward the head. Do whatever seems most comfortable for you in your work space. You should chill any organs you hope to save as soon as possible. Rinse them thoroughly in cool water and chill them, wrapped loosely in butcher paper, in the refrigerator. They need to be kept between 33 and 40 degrees F.

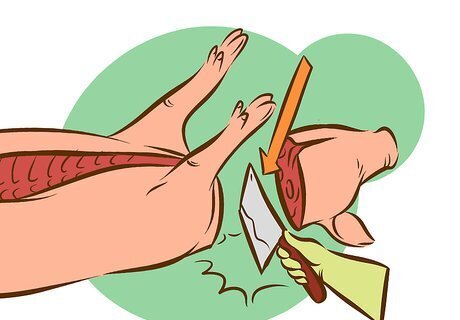

Remove the head. Behind the ears, work your knife in a circular direction around the throat to separate the head, using the jawline as a guide. As you separate the meat and expose the neck bone, you might need to get in there with a cleaver to break through the vertebrae with firm chop. If you want to remove the head and leave the jowls intact, cut toward the corner of the mouth, under the ears, separating the meat. The jowls are great for making jowl bacon, while others prefer to clean and keep the head intact for use in making head cheese. You can also remove the feet at the "wrist" knuckle, just up from the top each hoof. Use a hacksaw or a sawzall to slice through the joint and remove the feet.

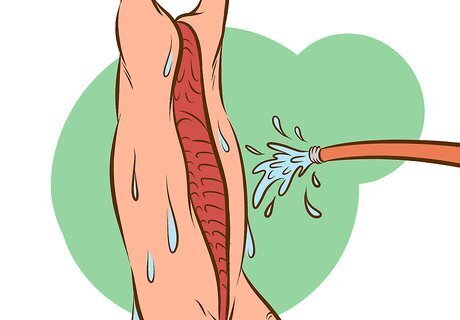

Clean the cavity thoroughly with water. Little hairs can be especially tenacious when you're processing out a hog. They'll stick to fat and be hard to find. Before you let the meat rest for a day to process it, it's important to give it another good rinsing with cool, clean water, letting it hang and dry thoroughly before moving it into the cold.

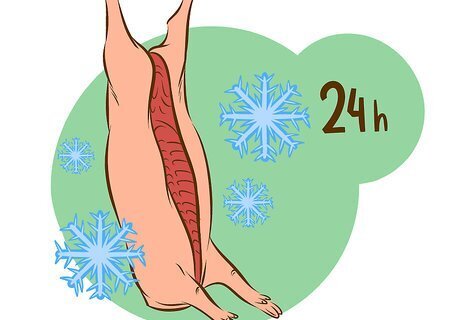

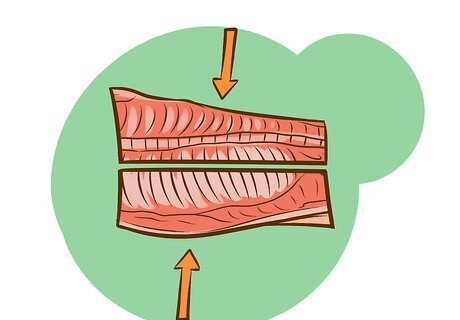

Chill the carcass for at least 24 hours before breaking it down. To dry out the meat some, the hog will need to be aged for about a day in cold temperature, between 30 and 40 degrees F. A walk-in fridge is the easiest way to do this, or processing your hot during a very cold season, in which you'll be able to do it in a shed or garage. Making the cuts necessary to break down the pork is almost impossible with warm, or even room-temperature meat. The whole process of making the necessary butchers' cuts are a lot easier with cold meat. You can also do an "ice brine," by filling a vat large enough to hold the hog with ice, with a few handfuls of table salt to keep the temperature down. Pack the meat onto the ice to cool it down. If you just don't have the space and can't let the meat sit, you need to break it down into a manageable size and get it cooled down. If space is at a premium, some people will use the sawmill or a manual hacksaw to cut through the backbones, as well as the pelvic bone, separating the hog into two halves. This will be the next step, regardless, so it's a good idea to do it whenever it's the most convenient for storage.

Processing the Pork

Remove the hams. Lay one half cut-side up, and find where the spine ends, near the fleshy part of the thigh (that's the ham) on that side. Start with a sharp boning knife to expose the ham. Trim back the belly by following the contour of the ham back toward the spine, cutting into the narrowest point. Turn your knife and cut straight down, until you hit the tip of the pelvic bone. At that point, switch your knife for the hacksaw (or your heavier cleaver) and cut through the bone to remove the ham. You should be able to see this point relatively easily, if your cut along the backbone was centered well. Hams are typically cured or smoked, so it's also a good idea to trim it up to make it uniform, especially if you've got an especially fatty ham. The wedge-shaped meat left near the spine after removing the ham is a premium cut, perfect for roasts. It's, in fact, where the phrase "high on the hog," comes from.

Remove the shoulder. To remove the shoulder, flip the side of pork over so the skin side is facing up. Pull the limb up, exposing the "underarm" of the shoulder, and work your knife into the connective tissue underneath. You'll only have to use your knife to continue working toward the joint, which should pull away easily by pulling it back on itself. Pork shoulder or "butt" is the best pork for slow-cooking and making pulled pork. It's a fatty cut, and going low-and-slow on the smoker will make for an excellent fork-tender meal.

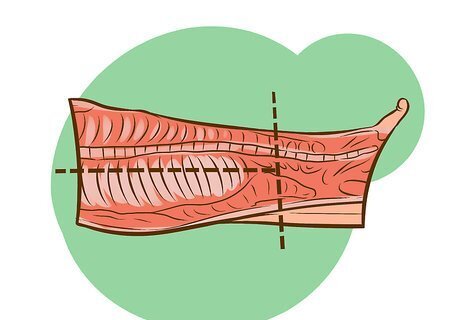

Remove the chops and tenderloin. Flip the side over again, cut-side up. From the smallest rib at the narrow end of the side, count up to the third or fourth rib and use the cleaver to cut through the backbone at that point, between the ribs. Remove everything below that line and reserve the meat for the grinder, or discard it. If you've got an electric butcher's saw, this is much easier. To find the chops, turn the side and look at it head-on, looking down the spine from the side that had the shoulder. Find the "eye" of the loin, which should run alongside the backbone. It's a thin quarter-sized (maybe larger or smaller, depending) dark patch of meat that runs alongside the spine, surrounded by a circle of fat. Perpendicular to the ribs, use the cleaver or saw to cut through the ribs, separating the tenderloin section, which you can separate into chops, from the lower section of ribs, which contains the bacon and the rib racks. Turn the tenderloin section lengthwise, so you can cut slices and form pork chops, as if you were cutting slices of bread. Start with the knife, cutting through to the bone, before switching back over to the saw. You want them to be even, about 2 inches (5.1 cm) thick, cutting through the bone to retain it. It's difficult going, if you're doing it by hand, so use a sawzall or butcher's saw if at all possible. It's a good idea to clean up the bone shards as even as possible, so they won't tear through the butcher paper in the fridge, which can promote spoilage. Have a partner go back over each chop with a metal scour pad to thin out any burrs and trim excess fat off, leaving no more than 3/4 of an inch of each. If there are bone shards, wipe them down with some cool water, cleaning them up as you work.

Separate the bacon. The lower, thinner section of the side contains everyone's favorite pork: the ribs and the bacon. It's best to separate the bacon, first. It's just below where the ribs end, and should appear to be quite fatty. To remove it, insert your knife under the ribs, cutting through the connective tissue and pulling the ribs back and away. Leave the cartilage attached to the rib-section, and not the bacon. Use that as you cutting line. It should come off quite easily. You can slice the bacon, or leave it whole for easier storage, until you're ready to do something with it. Leave the rib section whole, or separate into portions of ribs if you want. It's more common to leave the side whole.

Bone out the neck and grind up some sausage. The only remaining meat is usually best reserved for grinding up into sausage. If you have access to a meat grinder, you can grind pork to make sausage or basic ground pork. It's usually best to re-chill the meat before feeding it into the grinder, since cooler meat tends to grind up more uniformly. Cut even with the bone along the neck to flay the meat out and separate the bone. It doesn't have to be super-clean, since it's going into the grinder.

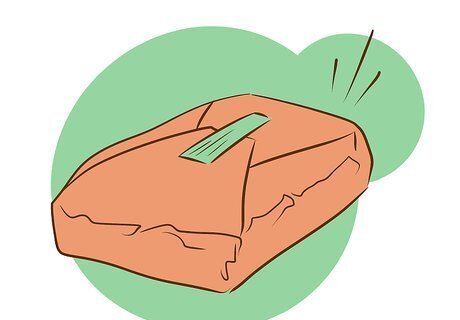

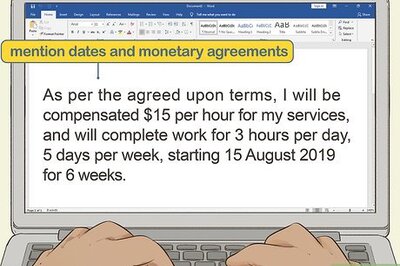

Store the meat properly. As soon as you portioned out the pork, it's important that you wrap it neatly in clean butcher paper, label it with the cut and date using a marker. You can refrigerate the meat you plan on using right away and find freezer space for the rest of it. There's going to be a lot of meat to deal with, so it's usually more common to freeze most of it immediately. It's a good idea to double-wrap pork in butcher paper, which is particularly susceptible to freezer burn and spoilage from the cold. This is especially the case in larger portions that have sharp bone shards that can cut through the paper.

Comments

0 comment