views

Seeing the Big Picture

Define the purpose of the curriculum. Your curriculum should have clear topic and purpose. The topic should be appropriate for the age of the students and the environment in which the curriculum will be taught. If you are asked to design a course, ask yourself questions about the general purpose of the course. Why am I teaching this material? What do students need to know? What things do they need to learn how to do? For example, in developing a summer writing course for high school students, you’ll have to think specifically about what you want the students to get out of the class. A possible purpose could be to teach students how to write a one-act play. Even if a topic and course are assigned to you, still ask yourself these questions so you have a good understanding of the curriculum's purpose.

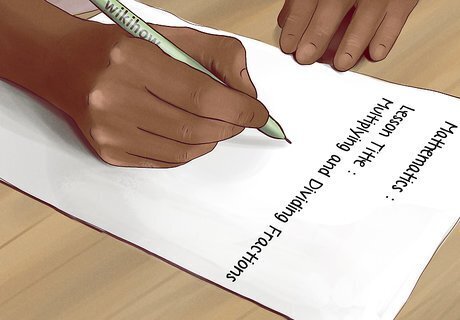

Choose an appropriate title. Depending on the learning objective, titling the curriculum may be a straightforward process or one that requires greater thought. A curriculum for GED students can be called "GED Preparation Curriculum." A program designed to assist adolescents with eating disorders might require a carefully thought-out title that is attractive to teenagers and sensitive to their needs.

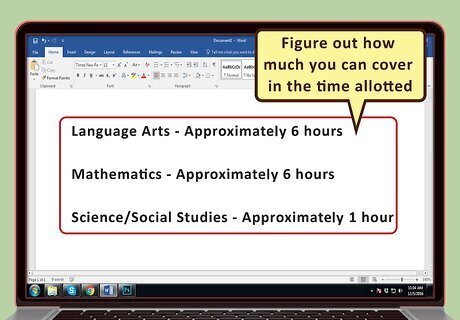

Establish a timeline. Talk to your supervisor about how much time you will have to teach the course. Some courses last a full year and others last only one semester. If you are not teaching in a school, find out how much time is allotted to your classes. Once you have a timeline, you can begin to organize your curriculum into smaller sections.

Figure out how much you can cover in the time allotted. Use your knowledge of your students (age, ability, etc.) and your knowledge of the content to get a sense of how much information you will be able to cover in the time you were given. You do not need to plan activities just yet, but you can start to think about what is possible. Consider how often you will see the students. Classes that meet once or twice per week may have a different outcome than classes that meet every day. For example, imagine that you are writing a theater curriculum. The difference between a two-hour class that meets once a week for three weeks, and a two-hour class that meets every day for three months is significant. In those three weeks, you might be able to put on a 10-minute play. Three months, on the other hand, may be enough time for a full production. This step may not apply to all teachers. Grade schools often follow state standards that outline the topics that need to be covered over the course of the year. Students often take tests at the end of the year, so there is much more pressure to cover all the standards.

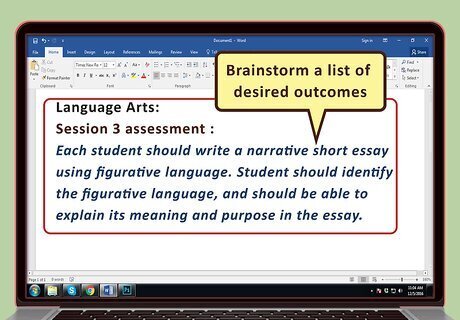

Brainstorm a list of desired outcomes. Make a list of the content you want your students to learn and what they should be able to do by the end of the course. It will later be important to have clear objectives that outline the skills and knowledge your students will acquire. Without these objectives, you will not be able to evaluate students or the efficacy of the curriculum. For example, in your summer playwriting course, you might want students to learn how to write a scene, develop well-rounded characters, and create a storyline. Teachers working in public schools in the United States are expected to follow government standards. Most states have adopted the Common Core State Standards, which explain exactly what students should be able to do by the end of the school year from grades K-12.

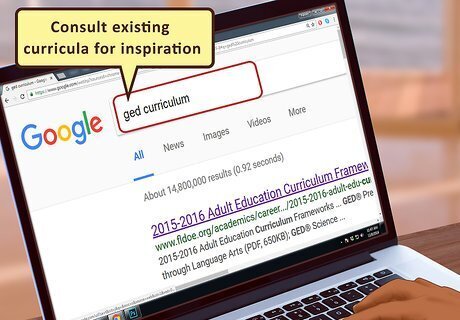

Consult existing curricula for inspiration. Check online for curricula or standards that have been developed in your subject area. If you are working in a school, check with other teachers and supervisors about curricula from previous years. Having a sample to work from makes developing your own curriculum much easier. For example, if you're teaching a playwriting class, you could do an online search for "Playwriting class curriculum" or "Playwriting course standards."

Filling in the Details

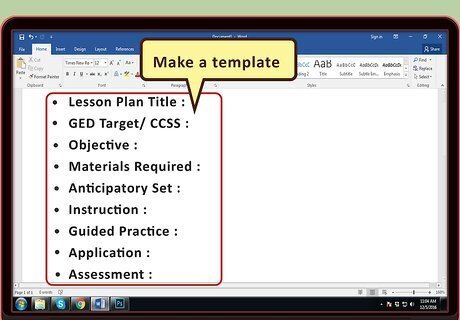

Make a template. Curricula are usually graphically organized in a way that includes a space for each component. Some institutions ask educators to use a standardized template, so find out what is expected of you. If no template is provided, find one online or create your own template. This will help you keep your curriculum organized and presentable.

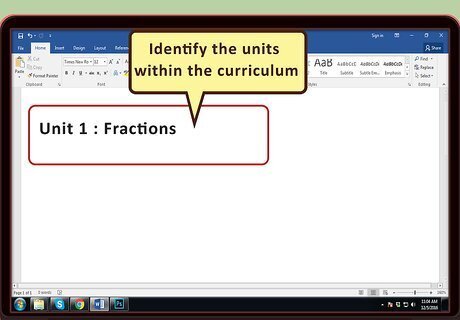

Identify the unit titles within the curriculum. Units, or themes, are the main topics that will be covered in the curriculum. Organize your brainstorm or state standards into unified sections that follow a logical sequence. Units can cover big ideas like love, planets, or equations, and important topics like multiplication or chemical reactions. The number of units varies by curriculum and they can last anywhere between one week and eight weeks. A unit title can be one word or a short sentence. A unit about character development, for example, could be called, “Creating deep characters.”

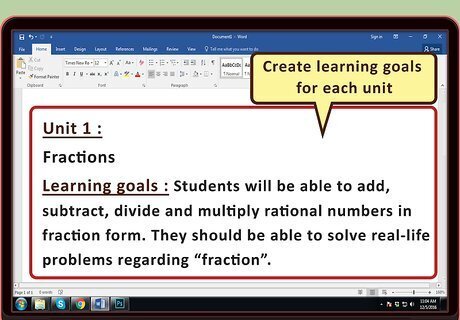

Create learning goals for each unit. Learning goals are the specific things that students will know and be able to do by the end of the unit. You already gave this some thought when you first brainstormed ideas for the class, now you have to be more specific. As you write your learning goals, keep important questions in mind. What does the state require students to know? How do I want my students to think about this topic? What will my students be able to do? Often, you can pull learning goals right from common core standards. Use SWBAT (Students will be able to). If you get stuck, try starting each learning goal with “Students will be able to…” This works for both skills and content knowledge. For example, “Students will be able to provide a two-page written analysis of the reasons behind the Civil War.” This requires students to both know information (causes of the Civil War) and do something with the information (written analysis). EXPERT TIP Joseph Meyer Joseph Meyer Math Teacher Joseph Meyer is a High School Math Teacher based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He is an educator at City Charter High School, where he has been teaching for over 7 years. Joseph is also the founder of Sandbox Math, an online learning community dedicated to helping students succeed in Algebra. His site is set apart by its focus on fostering genuine comprehension through step-by-step understanding (instead of just getting the correct final answer), enabling learners to identify and overcome misunderstandings and confidently take on any test they face. He received his MA in Physics from Case Western Reserve University and his BA in Physics from Baldwin Wallace University. Joseph Meyer Joseph Meyer Math Teacher Teach foundational skills so all students grasp the basics. Proactively address the challenges and learning obstacles your students would face, and work to close the achievement gap between high and low performers. Create a collaborative environment where all students have the opportunity to thrive.

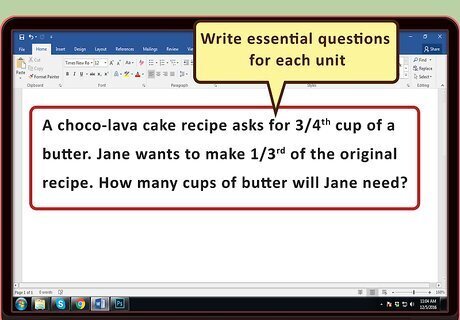

Write essential questions for each unit. Every unit needs 2-4 general questions that should be explored throughout the unit. Essential questions guide students to understand the more important parts of the theme. Essential questions are often big, complex questions that can’t always be answered in one lesson. For example, an essential question for a middle school unit about fractions might be, “Why doesn’t using division always make things smaller?” An essential question for a unit on character development might be, “How does a person’s decisions and actions reveal aspects of their personality?”

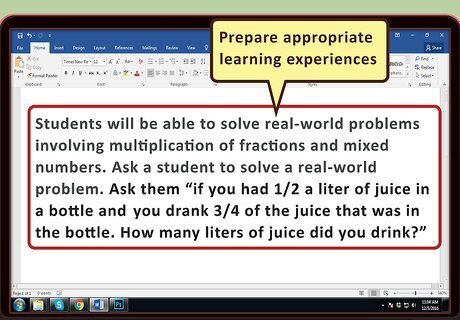

Prepare appropriate learning experiences. Once you have an organized set of units, you can begin to think about what kinds of materials, content, and experiences students will need in order to gain an understanding of each theme. This can be covered by the textbook you will use, texts you plan to read, projects, discussions, and trips. Keep your audience in mind. Remember that there are many ways for students to acquire skills and knowledge. Try to choose books, multimedia, and activities that will engage the population you are working with.

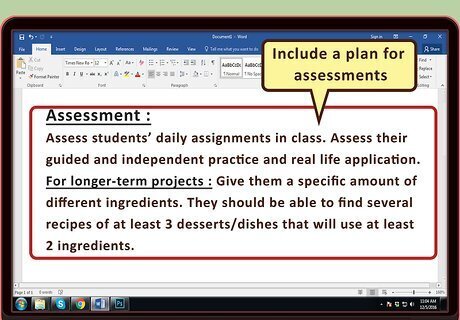

Include a plan for assessments to evaluate it. Students need to be evaluated on their performance. This helps the student know if they were successful in understanding the content, and it helps the teacher know if they were successful in delivering the content. Additionally, assessments help the teacher determine if any changes need to be made to the curriculum in the future. There are many ways to assess student performance, and assessments should be present throughout each unit. Use formative assessments. Formative assessments are usually smaller, more informal assessments that provide feedback on the learning process so you can make changes to the curriculum throughout the unit. Although formative assessments are usually a part of the daily lesson plan, they can also be included in the unit descriptions. Examples include journal entries, quizzes, collages, or short written responses. Include summative assessments. Summative assessments occur once a full topic has been covered. These assessments are appropriate for the end of a unit or at the end of the course. Examples of summative assessments are tests, presentations, performances, papers, or portfolios. These assessments range from touching on specific details to answering essential questions or discussing larger themes.

Making it Work

Use the curriculum to plan lessons. Lesson planning is usually separate from the curriculum development process. Although many teachers do write their own curricula, this is not always the case. Sometimes the person who wrote the curriculum is not the same person who will teach it. Either way, make sure you that what is outlined in the curriculum is used to guide lesson planning. Transfer the necessary information from your curriculum to your lesson plan. Include the name of the unit, the essential questions, and the unit goal that you are working on during the lesson. Ensure that lesson objectives lead students to reach the unit goals. Lesson objectives (also called aims, goals, or “SWBAT”) are similar to unit goals, but must be more specific. Remember that students should be able to complete the objective by the end of the lesson. For example, “Students will be able to explain four causes of the Civil War” is specific enough that it can be tackled in one lesson.

Teach and observe the lessons. Once you’ve developed the curriculum, put it into action. You won’t know if it is working until you try it out with real teachers and real students. Be aware of how students respond to the topics, teaching methods, assessments, and lessons.

Make revisions. Reflect on how the students respond to the material. This can happen in the middle of the course, or once it has already finished. Revisions are important, especially since standards, technology, and students are always changing. Ask key questions when you revise the curriculum. Are the students reaching the learning goals? Are they able to answer the essential questions? Are students meeting state standards? Are students prepared for the learning beyond your class? If not, consider making revisions the content, teaching styles, and sequence. You can revise any aspect of the curriculum, but everything must be aligned. Remember that any revisions you make to general topics need to be reflected in the other areas. For example, if you change a unit topic, remember to write new essential questions, objectives, and assessments.

Comments

0 comment