views

Creating Computer Animation

Decide whether you want to specialize in 2-D or 3-D animation. Computer animation makes doing either two-dimensional or three-dimensional animation easier than doing the work by hand. Three-dimensional animation requires learning additional skills besides animation. You'll need to learn how to light a scene, and also how to create the illusion of texture.

Choose the right computer equipment. How much computer you need depends on whether you're doing 2-D or 3-D animation. For 2-D animation, a fast processor is helpful, but not absolutely necessary. Nonetheless, get a quad-core processor if you can afford it, and at least a dual-core processor if you're buying a used computer. For 3-D animation, however, you want the fastest processor you can afford because of all the rendering work you'll do. You'll also want to have a significant amount of memory to support that processor. You'll more than likely spend several thousand dollars on a new computer workstation. For either form of animation, you'll want as large a monitor as your planned work area can accommodate, and you may want to consider a two-monitor setup if you have several detail-oriented program windows open at once. Some monitors, such as the Cintiq, are designed specifically for animation. You should also consider using a graphics tablet, an input device connected to your computer with a surface you draw on with a stylus, such as the Intuos Pro, in place of a mouse. Starting out, you may want to use a cheaper stylus pen to trace over your pencil drawings to transfer images to your computer.

Choose software appropriate to your skill level. Software is available for both 2-D and 3-D animation, with inexpensive options available for beginners and more sophisticated and more costly options you can migrate to as your budget and skill directs. For 2-D animation, you can produce animated images quickly using Adobe Flash, with the help of one of the many free tutorials available. When you're ready to learn to animate frame-by-frame, you can use a graphics program like Adobe Photoshop or a program that has a feature similar to Photoshop's Timeline feature. For 3-D animation, you can start with free programs like Blender and then move on to more sophisticated programs such as Cinema 4D or the industry standard, Autodesk Maya.

Practice. Immerse yourself in the software you've chosen to use, learning how to create with it and then actually sitting down and creating animations of your own. Compile these animations into a demonstration reel that you can show to others, either one-on-one or online. When exploring your animation software package, take a look at “Part Three: Creating Pen-and-Ink Animation” if your software is for 2-D animation and “Part Four: Creating Stop-Motion Animation” to determine what portions of the process the software will automate for you and what portions you'll have to do outside of it. You can post videos to your own website, which should be registered either under your own name or that of your business. You can also post to a site such as YouTube or Vimeo. Vimeo allows you to change which video you're posting without changing the link to it, which can be helpful when you've created your latest masterpiece.

General Animation Concepts

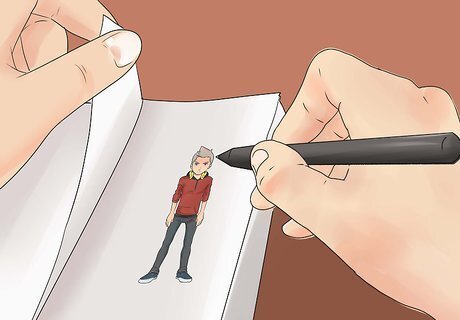

Plan out the story you want to animate. For simple animations, such as a flipbook, you can probably plan everything in your head, but for more complex work, you need to create a storyboard. A storyboard resembles an oversized comic strip, combining words and pictures to summarize the overall story or a given part of it. If your animation will use characters with complicated appearances, you'll also need to prepare model sheets showing how they appear in various poses and full-length.

Decide what parts of your story need to be animated and what parts can remain static. It usually isn't necessary, or cost-effective, to have every object in the story move in order to tell the story effectively. This is called limited animation. For a cartoon depicting Superman flying, you may want to show only the Man of Steel's cape flapping and clouds whizzing from the foreground into the background on an otherwise static sky. For an animated logo, you may want to have only the company name spin to call attention to it, and then for only a fixed number of times, so that people can read the name clearly. Limited animation in cartoons has the disadvantage of not looking particularly lifelike. For cartoons targeted to young children, this is not as much of a concern as in animated works intended for an older audience.

Determine what parts of the animation you can do repetitively. Certain actions can be broken down into sequential renderings that can be re-used multiple times in an animation sequence. Such a sequence is called a loop. Actions that can be looped include the following: Ball bouncing. Walking/running. Mouth movement (talking). Jumping rope. Wing/cape flapping.

You can find tutorials for some of these actions on the Angry Animator website at http://www.angryanimator.com/word/tutorials/.

Making a Flipbook

Get a number of sheets of paper you can flip through. A flipbook consists of a number of sheets of paper, usually bound at one edge, that creates the illusion of motion when you grasp the opposite edge with your thumb and flip through the pages. The more sheets of paper in the flipbook, the more realistic the motion appears to be. (A live-action motion picture uses 24 frames/images for each second, while most animated cartoons use 12.) You can make the actual book one of several ways: Staple or bind sheets of typing or construction paper together. Use a notepad. Use a pad of sticky notes.

Create the individual images. You can make the images in your flipbook animation one of several ways: Draw them by hand. If you do this, start with simple images (stick figures) and backgrounds and gradually tackle more complex drawings. You'll need to take care that the backgrounds are consistent from page to page to avoid a jittery appearance when you flip the pages. Photographs. You can take a number of digital photos, then print them out on sheets of paper and bind them together, or use a software application to create a digital flipbook. It's easiest to do this if your camera has a burst picture mode that lets you take a number of pictures as you hold down the button. Digital video. Some newlywed couples choose to create coffee-table flipbooks of their wedding, using a portion of the video shot during their wedding. Extracting individual video frames requires using a computer and video editing software, and many couples choose to upload their videos to online companies such as FlipClips.com.

Assemble the images together. If you've been hand-drawing the images in an already-bound notepad, the assembly is done for you. Otherwise, arrange the images with the first image at the bottom of the stack and the last image at the top and bind the sheets together. You may want to experiment with leaving out or rearranging a few of the images to make the animation appear jerkier or change the animation pattern before you bind the book together.

Flip through the pages. Bend the pages upward with your thumb and release them at an even speed. You should see a moving image. Pen-and-ink animators use a similar technique with preliminary drawings before coloring and inking them. They lay them one on top of each other, first to last, then hold down one of the edges as they flip through the drawings.

Creating Pen-and-Ink (Cel) Animation

Prepare the storyboard. Most animation projects created through pen-and-ink animation require a large team of artists to produce. This requires creating a storyboard to guide the animators, as well as to communicate the proposed story to producers before the actual drawing work begins.

Record a preliminary soundtrack. Because it's easier to coordinate an animated sequence to a soundtrack than a soundtrack to an animated sequence, you need to record a preliminary, or “scratch” soundtrack consisting of these items: Character voices Vocals to any songs A temporary musical track. The final track, along with any sound effects, are added in post-production. Animated cartoons before and into the 1930s did the animation first, then the sound. The Fleischer Studios did so in their earliest Popeye cartoons, which required the voice actors to ad-lib in between scripted places in the dialogue. This accounts for Popeye's humorous mutterings in cartoons such as “Choose Your Weppins.”

Make a preliminary story reel. This reel, or animatic, synchronizes the soundtrack with the storyboard to find and fix timing errors in either the soundtrack or the script. Advertising agencies make use of animatics as well as photomatics, a series of digital photographs sequenced together to make a crude animation. These are usually created with stock photos to keep the cost down.

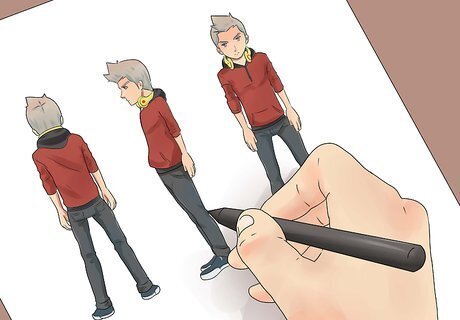

Create model sheets for major characters and important props. These sheets show the characters and items from a number of angles, as well as the style in which the characters are to be drawn. Some characters and items may be modeled in three dimensions using props called maquettes (small scale models). Reference sheets are also created for the backgrounds needed for where the action takes place.

Refine the timing. Go over the animatic to see what poses, lip movements, and other actions will be necessary for each frame of the story. Write these poses in a table called an exposure sheet (X-sheet). If the animation is primarily set to music, such as Fantasia, you can also create a bar sheet to coordinate the animation to the notes of the musical score. For some productions, the bar sheet can substitute for the X-sheet.

Lay out the story scenes. Animated cartoons are laid out similar to the way a cinematographer blocks out scenes in a live-action movie. For large productions, groups of artists devise the background appearance in terms of camera angles and paths, lighting, and shading, while other artists develop the necessary poses for each character in a given scene. For smaller productions, the director may make all these determinations.

Create a second animatic. This animatic is composed of the storyboard and layout drawings, with the soundtrack. When the director approves it, the actual animation begins.

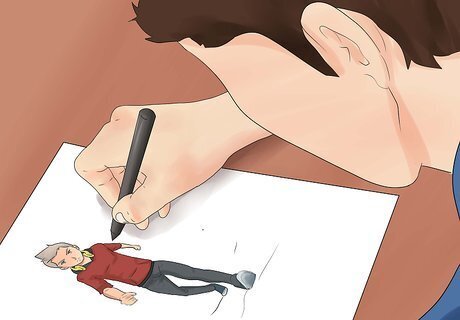

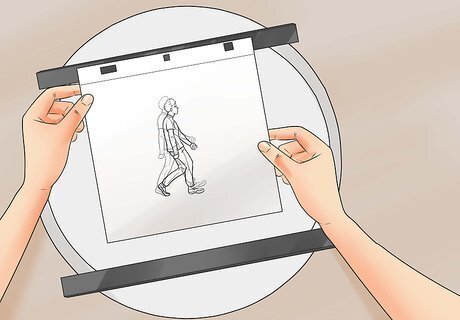

Draw the frames. In traditional animation, each frame is drawn in pencil on transparent paper perforated on the edges to fit into the pegs on a physical frame called a peg bar, which in turn is attached to either a desk or a light table. The peg bar keeps the paper from slipping so that each item in the scene being rendered appears where it is supposed to. Usually only the key points and actions are rendered first. A pencil test is made, using photos or scans of the drawings synchronized with the soundtrack to make sure the details are correct. Only then are the details added, after which they, too, are pencil-tested. Once everything has been so tested, it is sent to another animator, who redraws it to give it a more consistent look. In large productions, a team of animators may be assigned to each character, with the lead animator rendering the key points and actions and assistants rendering the details. When characters drawn by separate teams interact, the lead animators for each character work out which character is the primary character for that scene, and that character is rendered first, with the second character drawn to react to the first character's actions. A revised animatic is created during each phase of drawing, roughly equivalent to the daily “rushes” of live-action movies. Sometimes, usually when working with realistically drawn human characters, the frame drawings are traced over stills of actors and scenery on film. This process, developed in 1915 by Max Fleischer, is called rotoscoping.

Paint the backgrounds. As the frames are being drawn, the background drawings are turned into “sets” for photographing the character drawings against. Today usually done digitally, painting can be done traditionally with one of several media: Gouache (a form of watercolor with thicker pigment particles) Acrylic paint Oil Watercolor

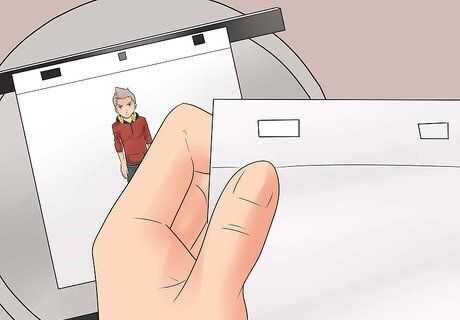

Transfer the drawings onto cels. Short for “celluloid,” cels are thin, clear sheets of plastic. As with the drawing paper, their edges are perforated to fit onto the pegs of a peg bar. Images can be traced from the drawings with ink or photocopied onto the cel. The cel is then painted on the reverse side using the same kind of paint to paint the background. Only the image of the character on object on the cel is painted; the rest is left unpainted. A more sophisticated form of this process was developed for the movie The Black Cauldron. The drawings were photographed on high-contrast film. The negatives were developed onto cels covered with light-sensitive dye. The unexposed portion of the cel was chemically cleaned, and small details were inked by hand.

Layer and photograph the cels. All the cells are placed on the peg bar; each cel carries a reference to indicate where it is placed on the stack. A sheet of glass is laid over the stack to flatten it, then it is photographed. The cels are then removed, and a new stack is created and photographed. The process is repeated until each scene is composed and photographed. Sometimes, instead of placing all the cels on a single stack, several stacks are created and the camera moves up or down through stacks. This kind of camera is called a multiplane camera and is used to add the illusion of depth. Overlays can be added over the background cel, over the character cels, or on top of all the cells to add additional depth and detail to the resulting image before it's photographed.

Splice the photographed scenes together. The individual images are sequenced together as film frames, which, when run in sequence, produce the illusion of motion.

Creating Stop-Motion Animation

Prepare the storyboard. As with other forms of animation, a storyboard provides a guide to the animators and a means to communicate to others how the story is to flow.

Choose the kind of objects to be animated. As with pen-and-ink animation, stop-motion animation relies on creating numerous pictures of images to be displayed in rapid sequence to produce the illusion of motion. Stop-motion animation, however, normally uses three-dimensional objects, although this is not always the case. You can use any of the following for stop-motion animation: Paper cut-outs. You can cut or tear pieces of paper into parts of human and animal figures and lay them against a drawn background to produce a crude two-dimensional animation. Dolls or stuffed toys. Best known with Rankin-Bass' animated productions such as Rudolph, The Red-Nosed Reindeer or Santa Claus Is Coming to Town and Adult Swim's Robot Chicken, this form of stop-motion dates back to Albert Smith and Stuart Blackton's 1897 The Humpty Dumpty Circus. You'll have to create cutouts for the various lip patterns to attach to your stuffed animals if you want to have them move their lips when they speak, however. Clay figures. Will Vinton's Claymation animated California Raisins are the best-known modern examples of this technique, but the technique dates back to 1912's Modelling Extraordinary and was the method that made Art Clokey's Gumby a TV star in the 1950s. You may need to use armatures for some clay figures and pre-sculpted leg bases, as Marc Paul Chinoy did in his 1980 film I go Pogo. Models. Models can be either of real or fantasy creatures or vehicles. Ray Harryhausen used stop-motion animation for the fantastic creatures of such movies as Jason and the Argonauts and The Golden Voyage of Sinbad. Industrial Light & Magic used stop-motion animation of vehicles to make the AT-ATs walk across the icy wastes of Hoth in The Empire Strikes Back.

Record a preliminary soundtrack. As with pen-and-ink animation, you'll need to have a scratch soundtrack to synchronize the action to. You may need to create an exposure sheet, a bar sheet, or both.

Synchronize the soundtrack and storyboard. As with pen-and-ink animation, you want to work out the timing between the soundtrack and the animation before you start moving objects around. If you plan to have speaking characters, you'll have to work out the correct mouth shapes for the dialog they're to utter. You may also find it necessary to create something similar to the photomatic described in the section about pen-and-ink animation.

Lay out the story scenes. This part of stop-motion animation would also be similar to how a cinematographer blocks out a live-action movie, even more so than for pen-and-ink animation, since you're most likely working in three dimensions as in a live-action movie. As with live-action film, you'll more likely have to be concerned with actually lighting a scene as opposed to drawing in the effects of light and shadow as you would in pen-and-ink animation.

Set up and photograph the components of the scene. You'll probably want to have your camera mounted on a tripod to keep it steady during the shooting sequence. If you have a timer that lets you take pictures automatically, you may want to use it if you can set it for long enough periods to let you adjust the components during the scene.

Move the items that need to be moved and photograph the scene again. Repeat this until you have completed photographing the entire scene from start to finish. Animator Phil Tippett developed a way to have some of the moving of models controlled by computer to produce more realistic motions. Called “go motion,” this method was used in The Empire Strikes Back, as well as in Dragonslayer, RoboCop, and RoboCop II.

Assemble the photographed images into a sequence. As with photographed cels in pen-and-ink animation, the individual shots from stop-motion animation become film frames that produce the illusion of motion when run one after the other.

Comments

0 comment