views

New Delhi: The first thing that disappeared was the annoying sound of a power drill up the street, from a house under construction.

Then the newspapers.

Then the fruit sellers, the taxis, the rickshaws and chicken.

Day by day, life under coronavirus lockdown in India took away something else, usually something good. And nearly six weeks into it, much of this country is still frozen.

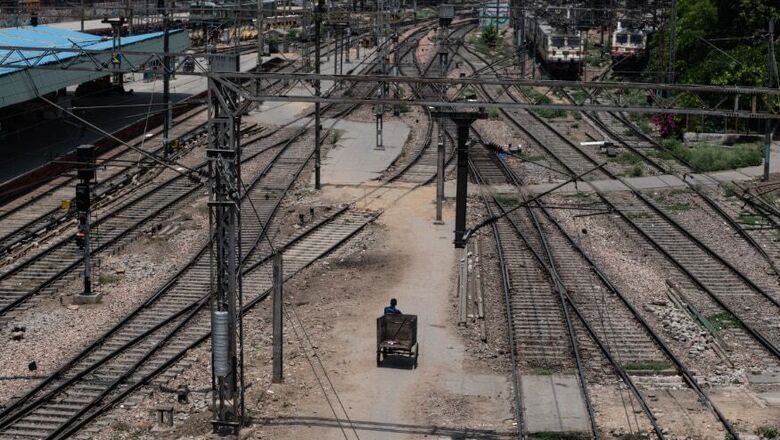

In many cities like New Delhi, practically nothing is moving on the roads. People stay indoors, as instructed, emerging only to collect the basic necessities. One friend who gets his food delivered told me he hasn’t left his house for a month.

All the airlines are grounded. Schools and offices are closed. The only businesses that I’ve seen operating are food shops, pharmacies and banks. The banks have lines running out the door and down the sidewalk where red circles have been spray-painted for people to stand in, 6 feet apart, like little islands.

The other day, I drove to Delhi’s outskirts. India is a place rightly known for teeming crowds and riotous traffic. There seems to be a national aversion to sticking to your lane, so I felt almost guilty blazing down an empty highway, past miles of shuttered shops, with no one to cut me off.

Whenever we turned off the highway, every village, no matter how small, was barricaded — some with oil drums, others with rope. Behind the barricades stood villagers carrying sticks to keep strangers out and wearing frayed bandannas over their faces, the virus vigilantes.

Even the sky above us is different these days. New Delhi is usually one of the world’s most polluted cities; its ceiling is invariably smudge gray. But now with so few cars and factories running, the air here is cleaner than it has been in decades.The weather that first weekend under lockdown, in late March, was especially lovely: mid-80s, breezy, clear skies. So on the following Monday when I saw The New York Times’ driver, Jag Singh, one of the few Indians I now see on a regular basis because of our isolation, I asked if he had managed to get outside.

“No.” Did his neighbors? Again, “no.”

Having seen the photos of some Americans rushing to beaches as soon as they were allowed, I asked why he thought Indians felt so constrained.His answer came quickly: “Everyone’s scared. People are saying if they get sick, where will they go?”That explained a lot. It explained why I wasn’t seeing anyone in my neighborhood venturing into the parks or strolling under the banyan trees. It explained why few people in India were testing the lockdown limits.

It’s not that they are automatically more willing to follow the rules than say, California’s sun lovers who were not nearly social distancing. It’s that in this case, Indians are more scared.

They’re scared of catching a highly contagious disease, and they don’t trust that a beleaguered health care system will save them. Or they’re scared about how they’ll pay for it, even if they get the care they need.

India has a lot of great doctors but the ratio of doctors or hospital beds per person is much lower than in the West. And many people here survive on a few dollars a day.

India seems to be doing better than many richer countries in containing the virus, at least so far. With reported infections relatively low, around 35,000, the government is trying to loosen the national tourniquet and reopen some industries, such as agriculture and select manufacturing.

But many Indians don’t want to take the tourniquet off, even if it is stanching the economy’s flow.

A good chunk of the population has decided that the best way to protect themselves is not only to stick to the lockdown rules, but to go above and beyond them, like the volunteer virus squads who sealed off entire villages. Even people in my Delhi neighborhood have become lockdown enthusiasts.

A few weeks ago when I biked with my two sons to the neighborhood milk depot — perfectly permissible under lockdown rules — someone leaned out a window and boomed: “Go home!”

My kids’ eyes widened. I pedaled away shaken. Did he mean back to our apartment? Or to America? Many people here have blamed foreigners for bringing India the coronavirus.

So my family now does what everyone does: We stay inside, looking out the windows at one beautiful day passing after another. We used to sit around the table and share upcoming plans. Now we don’t have any.

We are marooned in the present tense. We couldn’t leave New Delhi even if we wanted to. I crave sitting in the open night air in a Rajasthani village, listening to tabla music. Or simply standing in a freshly turned field that smells of earth and shaking a farmer’s hand.

Lockdown is a blow to what I do and why I’ve dragged my family into this. Foreign correspondents relocate themselves and their families to soak up new experiences and transmit as much of that as possible to readers back home — not just the news but also the feel of a place, the humanity. We wither doing Zoom calls from our couches.

But there is so much suffering around me, I’m not focusing on that right now.

I get out a couple of times a week with my journalist pass, and just a few days ago I met a mother and her 9-year-old daughter moving from spray-painted circle to spray-painted circle down a sidewalk in a food line. The mother was a maid who had lost her job because of the lockdown. The daughter told me coronavirus came from stones that fell from the sky.

They had zero money and I could tell from how listlessly they accepted their two pieces of fried bread and two lumps of potato curry that they hated taking handouts.

Behind them, in the bright sun, were hundreds of people just like them, marching slowly forward.

Jeffrey [email protected] The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment