views

sinc

x

=

{

sin

x

x

if

x

≠

0

,

1

if

x

=

0.

{\displaystyle \operatorname {sinc} x={\begin{cases}{\dfrac {\sin x}{x}}&{\text{if }}x\neq 0,\\\ \ \ 1&{\text{if }}x=0.\end{cases}}}

This function frequently pops up first as an example of evaluation of limits, and it is well-known that

lim

x

→

0

sin

x

x

=

1

;

{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}=1;}

hence, why the function at 0 is defined to be that limiting value. However, this function primarily finds wider applicability in signal analysis and related fields. For example, the Fourier transform of a rectangular pulse is the sinc function.

Evaluating the integral of this function is rather difficult because the antiderivative of the sinc function cannot be expressed in terms of elementary functions. This means that we cannot directly apply the fundamental theorem of calculus. We will instead employ Richard Feynman's trick of differentiating under the integral. We will also show a more general solution using residue theory.

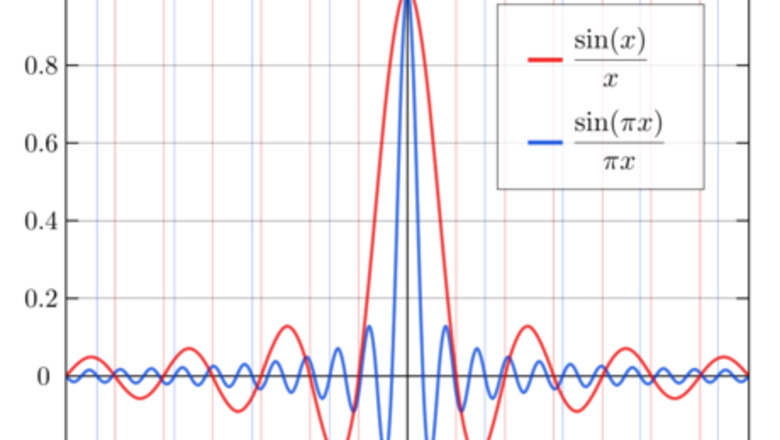

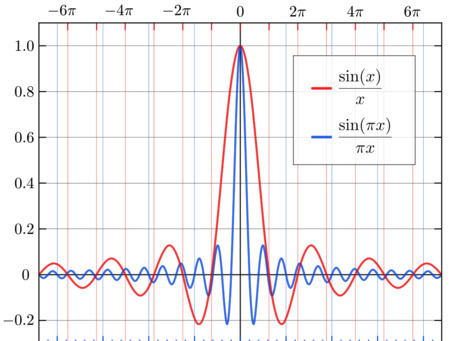

Differentiation Under the Integral

Begin with the integral to be evaluated. We are evaluating over the entire real line, so the limits will be positive and negative infinity. Above is a visualization of the function with both definitions - unnormalized (in red) and normalized (in blue). We will be evaluating the unnormalized sinc function. ∫ − ∞ ∞ sin x x d x {\displaystyle \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {\sin x}{x}}\mathrm {d} x} \int _{{-\infty }}^{{\infty }}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x We see from the graph that sin x x {\displaystyle {\frac {\sin x}{x}}} {\frac {\sin x}{x}} is an even function, which can be confirmed by looking at the function above. Then, we can factor out a 2. 2 ∫ 0 ∞ sin x x d x {\displaystyle 2\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\sin x}{x}}\mathrm {d} x} 2\int _{{0}}^{{\infty }}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x The integral above with bounds of 0 to infinity is also known as the Dirichlet integral.

Define a function G ( t ) {\displaystyle G(t)} G(t). The purpose of defining such a function with an argument t {\displaystyle t} t is so that we can work with an integral that is easier to evaluate, whilst meeting the conditions of the sinc integral for appropriate values of t . {\displaystyle t.} t. In other words, putting the e − t x {\displaystyle e^{-tx}} e^{{-tx}} term inside the integral is valid, since the integral converges for all t ≥ 0 , {\displaystyle t\geq 0,} t\geq 0, while setting t = 0 {\displaystyle t=0} t=0 recovers the original integral. This reformulation means that we are ultimately evaluating G ( 0 ) . {\displaystyle G(0).} G(0). G ( t ) = ∫ 0 ∞ sin x x e − t x d x {\displaystyle G(t)=\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\sin x}{x}}e^{-tx}\mathrm {d} x} G(t)=\int _{{0}}^{{\infty }}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}e^{{-tx}}{\mathrm {d}}x

Differentiate under the integral. We can move the derivative under the integration sign because the integral is being taken with respect to a different variable. While we do not justify this operation here, it is widely applicable for a great many functions. Keep in mind that t {\displaystyle t} t is to be treated as a variable throughout the evaluation, not a constant. d G d t = d d t ∫ 0 ∞ sin x x e − t x d x = ∫ 0 ∞ ∂ ∂ t e − t x sin x x d x = − ∫ 0 ∞ e − t x sin x d x {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {\mathrm {d} G}{\mathrm {d} t}}&={\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} t}}\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\sin x}{x}}e^{-tx}\mathrm {d} x\\&=\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\partial }{\partial t}}e^{-tx}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}\mathrm {d} x\\&=-\int _{0}^{\infty }e^{-tx}\sin x\mathrm {d} x\end{aligned}}} {\begin{aligned}{\frac {{\mathrm {d}}G}{{\mathrm {d}}t}}&={\frac {{\mathrm {d}}}{{\mathrm {d}}t}}\int _{{0}}^{{\infty }}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}e^{{-tx}}{\mathrm {d}}x\\&=\int _{{0}}^{{\infty }}{\frac {\partial }{\partial t}}e^{{-tx}}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x\\&=-\int _{{0}}^{{\infty }}e^{{-tx}}\sin x{\mathrm {d}}x\end{aligned}}

Evaluate d G d t {\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {d} G}{\mathrm {d} t}}} {\frac {{\mathrm {d}}G}{{\mathrm {d}}t}}. This is, in fact, the evaluation for the Laplace transform of sin x . {\displaystyle \sin x.} \sin x. The most basic way to evaluate this integral is by using integration by parts, which we work out below. See the tips for a more powerful way to integrate this. Pay attention to the signs. d G d t = e − t x cos x | 0 ∞ + ∫ 0 ∞ t e − t x cos x d x = e − t x cos x | 0 ∞ + [ t e − t x sin x | 0 ∞ + ∫ 0 ∞ t 2 e − t x sin x d x ] = e − t x cos x | 0 ∞ + t e − t x sin x | 0 ∞ − t 2 d G d t {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {\mathrm {d} G}{\mathrm {d} t}}&=e^{-tx}\cos x{\Big |}_{0}^{\infty }+\int _{0}^{\infty }te^{-tx}\cos x\mathrm {d} x\\&=e^{-tx}\cos x{\Big |}_{0}^{\infty }+\left[te^{-tx}\sin x{\Big |}_{0}^{\infty }+\int _{0}^{\infty }t^{2}e^{-tx}\sin x\mathrm {d} x\right]\\&=e^{-tx}\cos x{\Big |}_{0}^{\infty }+te^{-tx}\sin x{\Big |}_{0}^{\infty }-t^{2}{\frac {\mathrm {d} G}{\mathrm {d} t}}\end{aligned}}} {\begin{aligned}{\frac {{\mathrm {d}}G}{{\mathrm {d}}t}}&=e^{{-tx}}\cos x{\Big |}_{{0}}^{{\infty }}+\int _{{0}}^{{\infty }}te^{{-tx}}\cos x{\mathrm {d}}x\\&=e^{{-tx}}\cos x{\Big |}_{{0}}^{{\infty }}+\left[te^{{-tx}}\sin x{\Big |}_{{0}}^{{\infty }}+\int _{{0}}^{{\infty }}t^{{2}}e^{{-tx}}\sin x{\mathrm {d}}x\right]\\&=e^{{-tx}}\cos x{\Big |}_{{0}}^{{\infty }}+te^{{-tx}}\sin x{\Big |}_{{0}}^{{\infty }}-t^{{2}}{\frac {{\mathrm {d}}G}{{\mathrm {d}}t}}\end{aligned}} d G d t ( 1 + t 2 ) = ( 0 − 1 ) + ( 0 − 0 ) {\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {d} G}{\mathrm {d} t}}(1+t^{2})=(0-1)+(0-0)} {\frac {{\mathrm {d}}G}{{\mathrm {d}}t}}(1+t^{{2}})=(0-1)+(0-0) d G d t = − 1 1 + t 2 {\displaystyle {\frac {\mathrm {d} G}{\mathrm {d} t}}=-{\frac {1}{1+t^{2}}}} {\frac {{\mathrm {d}}G}{{\mathrm {d}}t}}=-{\frac {1}{1+t^{{2}}}}

Integrate both sides with respect to t {\displaystyle t} t. This recovers G ( t ) {\displaystyle G(t)} G(t) under a different variable. Since the integrand is the differential of a well-known function, this evaluation is trivial. − ∫ 1 1 + t 2 d t = − tan − 1 t + C {\displaystyle -\int {\frac {1}{1+t^{2}}}\mathrm {d} t=-\tan ^{-1}t+C} -\int {\frac {1}{1+t^{{2}}}}{\mathrm {d}}t=-\tan ^{{-1}}t+C Here, we recognize that G ( t ) = 0 {\displaystyle G(t)=0} G(t)=0 as t → ∞ {\displaystyle t\to \infty } t\to \infty for both this integral and the one defined in step 2. However, lim t → ∞ tan − 1 t = π 2 , {\displaystyle \lim _{t\to \infty }\tan ^{-1}t={\frac {\pi }{2}},} \lim _{{t\to \infty }}\tan ^{{-1}}t={\frac {\pi }{2}}, so C = π 2 {\displaystyle C={\frac {\pi }{2}}} C={\frac {\pi }{2}} as well. Therefore, G ( t ) = − tan − 1 t + π 2 . {\displaystyle G(t)=-\tan ^{-1}t+{\frac {\pi }{2}}.} G(t)=-\tan ^{{-1}}t+{\frac {\pi }{2}}.

Evaluate the sinc integral. Now that we have G ( t ) , {\displaystyle G(t),} G(t), where t ≥ 0 , {\displaystyle t\geq 0,} t\geq 0, we can substitute 0 for t {\displaystyle t} t and find that G ( 0 ) = π 2 . {\displaystyle G(0)={\frac {\pi }{2}}.} G(0)={\frac {\pi }{2}}. G ( 0 ) = ∫ 0 ∞ sin x x d x = π 2 {\displaystyle G(0)=\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\sin x}{x}}\mathrm {d} x={\frac {\pi }{2}}} G(0)=\int _{{0}}^{{\infty }}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x={\frac {\pi }{2}} Finally, we recall that to integrate over all the reals, we simply multiply by 2, as sinc x {\displaystyle \operatorname {sinc} x} \operatorname {sinc}x is an even function. ∫ − ∞ ∞ sin x x d x = π {\displaystyle \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {\sin x}{x}}\mathrm {d} x=\pi } \int _{{-\infty }}^{{\infty }}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x=\pi It is worth memorizing this answer, as it can pop up in multiple contexts.

Residue Theory

Consider the integral below. Recall that sin x {\displaystyle \sin x} \sin x is simply the imaginary part of the exponential function e i x . {\displaystyle e^{ix}.} e^{{ix}}. This integral is continuous except for the singularity at x = 0. {\displaystyle x=0.} x=0. ∫ − ∞ ∞ e i x x d x {\displaystyle \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {e^{ix}}{x}}\mathrm {d} x} \int _{{-\infty }}^{{\infty }}{\frac {e^{{ix}}}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x

Consider the contour integral with an indented contour. The easiest improper integrals evaluated using residue theory use a semicircular arc that traces the real line from some boundary − a {\displaystyle -a} -a to a {\displaystyle a} a and arcs counterclockwise back to − a , {\displaystyle -a,} -a, while a → ∞ . {\displaystyle a\to \infty .} a\to \infty . However, we cannot use this because of the pole at the origin. The solution is to use an indented contour that goes around the pole. ∫ Γ e i z z d z {\displaystyle \int _{\Gamma }{\frac {e^{iz}}{z}}\mathrm {d} z} \int _{{\Gamma }}{\frac {e^{{iz}}}{z}}{\mathrm {d}}z The contour Γ {\displaystyle \Gamma } \Gamma is split into four parts. We begin from − a {\displaystyle -a} -a and traverse the real line to some small number − ϵ . {\displaystyle -\epsilon .} -\epsilon . Then a semicircular arc γ ϵ {\displaystyle \gamma _{\epsilon }} \gamma _{{\epsilon }} with radius ϵ {\displaystyle \epsilon } \epsilon goes clockwise to ϵ {\displaystyle \epsilon } \epsilon on the real axis. This contour then goes to a , {\displaystyle a,} a, from which a semicircular arc γ a {\displaystyle \gamma _{a}} \gamma _{{a}}with radius a {\displaystyle a} a goes counterclockwise and back to − a . {\displaystyle -a.} -a. The important thing to note here is that this integral does not have any singularities within the contour, and is therefore 0. We can therefore write the following. ∫ − a − ϵ e i x x d x + ∫ ϵ a e i x x d x = − ∫ γ ϵ e i z z d z − ∫ γ a e i z z d z {\displaystyle \int _{-a}^{-\epsilon }{\frac {e^{ix}}{x}}\mathrm {d} x+\int _{\epsilon }^{a}{\frac {e^{ix}}{x}}\mathrm {d} x=-\int _{\gamma _{\epsilon }}{\frac {e^{iz}}{z}}\mathrm {d} z-\int _{\gamma _{a}}{\frac {e^{iz}}{z}}\mathrm {d} z} \int _{{-a}}^{{-\epsilon }}{\frac {e^{{ix}}}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x+\int _{{\epsilon }}^{{a}}{\frac {e^{{ix}}}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x=-\int _{{\gamma _{{\epsilon }}}}{\frac {e^{{iz}}}{z}}{\mathrm {d}}z-\int _{{\gamma _{{a}}}}{\frac {e^{{iz}}}{z}}{\mathrm {d}}z

Use Jordan's lemma to evaluate the γ a {\displaystyle \gamma _{a}} \gamma _{{a}} integral. Typically, for this integral to vanish, the degree of the denominator must be at least two greater than the degree of the numerator. Jordan's lemma implies that if such a rational function is multiplied by an e i z {\displaystyle e^{iz}} e^{{iz}} term, then the degree of the denominator need only be at least one greater. Therefore, this integral vanishes. ∫ γ a e i z z d z = 0 {\displaystyle \int _{\gamma _{a}}{\frac {e^{iz}}{z}}\mathrm {d} z=0} \int _{{\gamma _{{a}}}}{\frac {e^{{iz}}}{z}}{\mathrm {d}}z=0

Evaluate the γ ϵ {\displaystyle \gamma _{\epsilon }} \gamma _{{\epsilon }} integral. If you are familiar with contour integrals of 1 z {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{z}}} {\frac {1}{z}} involving circular arc contours, the example involves the fact that the integral depends on the angle that the arc traverses. In our example, the arc is being integrated from the angle π {\displaystyle \pi } \pi to 0 {\displaystyle 0} {\displaystyle 0} in a clockwise fashion. Such an integral will therefore equal − π i . {\displaystyle -\pi i.} -\pi i. We can generalize this result to arcs of any angle, but more importantly, for residues. See the tips for the theorem that this step uses. The residue at the origin is easily found to be Res ( 0 ) = 1. {\displaystyle \operatorname {Res} (0)=1.} \operatorname {Res}(0)=1. lim ϵ → 0 + ∫ γ ϵ e i z z d z = − π i Res ( 0 ) = − π i {\displaystyle \lim _{\epsilon \to 0^{+}}\int _{\gamma _{\epsilon }}{\frac {e^{iz}}{z}}\mathrm {d} z=-\pi i\operatorname {Res} (0)=-\pi i} \lim _{{\epsilon \to 0^{{+}}}}\int _{{\gamma _{{\epsilon }}}}{\frac {e^{{iz}}}{z}}{\mathrm {d}}z=-\pi i\operatorname {Res}(0)=-\pi i

Arrive at the answer to our integral. Because ϵ → 0 {\displaystyle \epsilon \to 0} \epsilon \to 0 and a → ∞ , {\displaystyle a\to \infty ,} a\to \infty , negate our result (see step 2) to arrive at our answer. ∫ − ∞ ∞ e i x x d x = ∫ − a − ϵ e i x x d x + ∫ ϵ a e i x x d x = π i {\displaystyle \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {e^{ix}}{x}}\mathrm {d} x=\int _{-a}^{-\epsilon }{\frac {e^{ix}}{x}}\mathrm {d} x+\int _{\epsilon }^{a}{\frac {e^{ix}}{x}}\mathrm {d} x=\pi i} \int _{{-\infty }}^{{\infty }}{\frac {e^{{ix}}}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x=\int _{{-a}}^{{-\epsilon }}{\frac {e^{{ix}}}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x+\int _{{\epsilon }}^{{a}}{\frac {e^{{ix}}}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x=\pi i

Consider the imaginary part of the integral above. The above result really gives us two real results. First of all, the integral of the sinc function immediately follows. Im ∫ − ∞ ∞ e i x x d x = ∫ − ∞ ∞ sin x x d x = π {\displaystyle \operatorname {Im} \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {e^{ix}}{x}}\mathrm {d} x=\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }{\frac {\sin x}{x}}\mathrm {d} x=\pi } \operatorname {Im}\int _{{-\infty }}^{{\infty }}{\frac {e^{{ix}}}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x=\int _{{-\infty }}^{{\infty }}{\frac {\sin x}{x}}{\mathrm {d}}x=\pi Second of all, the principal-valued integral of a related function cos x x {\displaystyle {\frac {\cos x}{x}}} {\frac {\cos x}{x}} follows as well if we take the real part of our result, which is 0.

Comments

0 comment