views

Researching

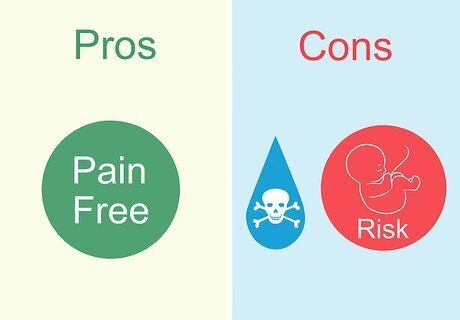

Understand the pros and cons of home birth. Up until quite recently in history, the vast majority of births occurred in the home. As of 2009, however, in the United States, only about 0.72% of all births were home births. Statistics for most other developed countries are similarly low. Despite their relative rarity in developed nations in the modern era, some pregnant people greatly prefer home births to hospital births. There are numerous reasons why a parent might choose a home birth over a hospital birth, and most home births are safe, although studies suggest home birth is associated with a higher risk of infant death, seizures, and nervous system disorders than hospital births. Though the elevated rate of complication is still not very high in absolute terms (corresponding with only several births experiencing complications per every 1,000), undecided parents should understand that home births may be slightly more risky than hospital births. On the other hand, home births offer certain advantages that hospital births may not be able to, including: Greater freedom for the person in labor to move, bathe, and eat as they see fit A greater ability for the person to adjust their position during labor The comfort of familiar surroundings and faces The ability to give birth without medical assistance (like the use of painkillers), if desired The ability to meet religious or cultural expectations for birth Lower overall cost, in some situations

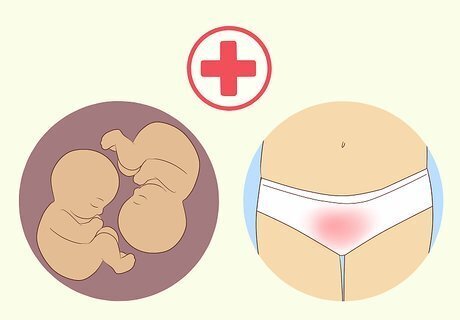

Know when home birth should not be attempted. In certain situations, births carry an increased risk of complication for the child, the parent, or both. In these situations, the health of the pregnant individual and their child outweigh any minor advantages a home birth may offer, so the birth should be carried out in a hospital, where experienced doctors and life-saving medical technology are available. Here are situations in which an expectant parent should definitely plan to give birth in a hospital: When the patient has any chronic health condition (diabetes, epilepsy, etc.) When the patient has undergone a C-section for a previous pregnancy If prenatal screening has revealed any health concerns for the unborn child If the patient has developed a pregnancy-associated health condition If the patient uses tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs If the patient has twins, triplets, etc. or if the child hasn't settled into a headfirst position for delivery If a birth is premature or late. In other words, don't plan a home birth before the 37th week of pregnancy or after the 41st week.

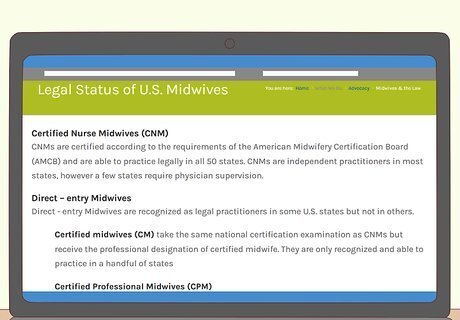

Know the legality of home birth. Generally, home births are not prohibited by most state or national governments. In the UK, Australia, and Canada, home birth is legal, and, depending on the circumstances, the government may provide funding for it. However, the legal situation in the United States surrounding midwives is somewhat more complicated. In the United States, it is legal in all 50 states to hire a certified nurse midwife (CNM). CNMs are certified nurses who usually work in hospitals—though it's rare for them to make house calls, it is legal to hire them for home births in every state. In 36 states and Washington, D.C., it is also legal to hire a direct-entry midwife or certified professional midwife (CPM). Direct-entry midwives are midwives who attained their status through self-study, apprenticeship, etc. and are not required to be a nurse or doctor. CPMs are certified by the North American Registry of Midwives (NARM). CPMs are not required to carry insurance and are not subject to peer review.

Planning the Birth

Make arrangements with a doctor or midwife. It's highly recommended that you have a certified midwife or doctor accompany you for your home birth. Make plans to have the midwife or doctor come to your home well in advance: meet and discuss your birth with them before your labor is likely to begin, and keep their number on hand so you can call if your labor begins unexpectedly. The Mayo Clinic also recommends making sure the doctor or midwife has easy access to the consultation of doctors at a nearby hospital, if possible. You may also want to consider finding or hiring a doula—someone who provides continuous physical and emotional support throughout labor. Wellness coach Giselle Baumet advises, “Since at home you have fewer options for pain medications, I recommend that you take a comprehensive course that includes the process of birth, how to cope with contractions, breathing and relaxation techniques, breastfeeding, and how to care for yourself during postpartum.”

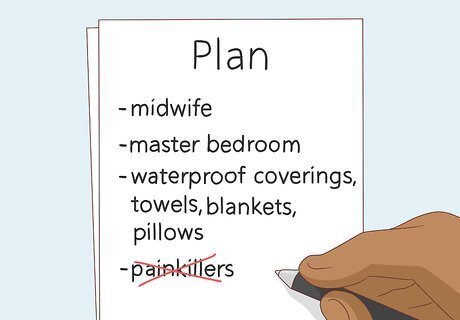

Decide on a plan for your childbirth experience. Giving birth is an emotionally and physically draining experience, to put it lightly. The last thing you'll want to do during labor, when you may be in intense distress, is to have to make quick, important decisions about the way the birth will proceed. It's far smarter to create and review an approximate plan for your birth well before you enter labor. Try to account for every step of your delivery, from beginning to end. Even if you're not able to follow your plan exactly, having the plan will likely give you peace of mind. In your plan, try to answer questions like the following ones: Besides the doctor/midwife, which people, if any, do you want present for the birth? Where do you plan to deliver? Note that, for much of your labor, you will be able to move around for comfort. What supplies should you plan on having? Talk to your doctor; usually, you'll want lots of extra towels, sheets, pillows, and blankets, plus waterproof coverings for the bed and floor. How will you manage the pain? Will you use medical painkillers, the Lamaze technique, or another form of pain management?

Arrange for transport to a hospital. The vast majority of home births are successful and free of complications. However, as with every birth, there is always a small chance that things can go wrong which threaten the health of the child and/or parent. Because of this, it's important to be prepared to rush the birth giver to a hospital in the event of an emergency. Keep a full tank of gas in your car, and keep your car well-stocked with cleaning supplies, blankets, and towels. Know the quickest route to the nearest hospital—you may even want to practice driving there.

Choose where you will deliver the baby. Though you'll be able to adjust your position and even walk around for most of your labor, it's a good idea to have a place in your home set aside as the final site of childbirth. Choose a safe, comfortable spot—many birth givers prefer their own bed, but it's possible to give birth on sofas or even on a soft part of the floor. Regardless of the location you choose, make sure that, by the time labor begins, it's been recently-cleaned and it's well-stocked with towels, blankets, and pillows. You'll probably also want to use a water-tight plastic sheet or covering to prevent blood stains. In a pinch, a clean, dry shower curtain will work as a water-tight barrier to prevent stains. Though your doctor or midwife will most likely have these things, you may also want to have sterile gauze pads and ties ready nearby for cutting the baby's cord.

Wait for signs of labor. Once you've made all the necessary preparations, simply wait for your labor to begin. On average, most pregnancies usually last about 38 weeks, though healthy labor can begin within a week or two of the 38 week mark. If you enter labor before the 37th week of pregnancy or after the 41st week, proceed immediately to a hospital. Otherwise, be prepared for any of the following signs of your labor beginning: Your water breaking Dilation of the cervix Bloody show (the discharge of a pinkish or brownish blood-tinged mucous) Contractions lasting 30 to 90 seconds

Giving Birth

Listen to your doctor or midwife. The healthcare professional you have chosen for your home birth has been trained to deliver babies safely and has been certified to do so. Always listen to your doctor or midwife's advice and do your best to follow it. Some of the things they may advise can temporarily cause your pain to increase. However, doctors and midwives ultimately want to help you get through your labor as quickly and safely as possible, so try to follow their commands as best you can. The rest of the advice in this section is intended merely as a rough guide; always defer to the advice of your doctor or midwife.

Stay calm and focused. Labor can be a prolonged, painful ordeal, and a certain degree of nervousness is almost inevitable. However, it's never a good idea to give in to thoughts of desperation or hopelessness. Do your best to stay as relaxed and lucid as possible. This will allow you to follow your doctor or midwife's instructions to the best of your ability, ensuring your labor is as quick and safe as possible. It's easiest to stay relaxed if you're in a comfortable position and breathing deeply.

Look for signs of complications. As previously noted, most home births occur without a hitch. However, complications are always a small possibility during childbirth. If you notice any of the following signs, proceed to a hospital immediately, as these may signify serious pregnancy complications which require the technology and expertise available at a hospital: Traces of feces appear in your amniotic fluid when your water breaks The umbilical cord drops into your vagina before the baby does You have vaginal bleeding not involved with your bloody show or if your bloody show contains an especially large amount of blood (normal bloody shows are pink, brown, or somewhat blood-tinged) You don't deliver the placenta after the child is born or the placenta isn't delivered intact Your baby isn't born head-first Your baby appears distressed in any way Labor does not progress into childbirth

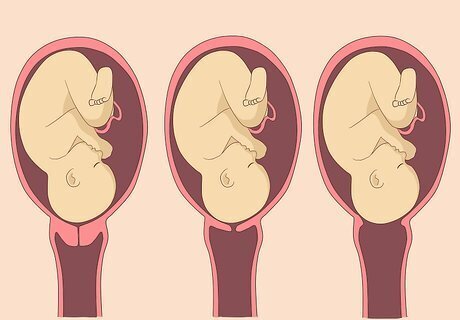

Have your attendant monitor the dilation of your cervix. During the first stage of labor, your cervix dilates, thinning and widening to allow for the passage of the baby. At first, discomfort may be minimal. Over time, your contractions will gradually become more frequent and more intense. You may start to feel pain or pressure in your lower back or abdomen that increases as your cervix dilates. As your cervix dilates, your attendant should perform frequent pelvic exams to monitor its progress. When it's fully dilated with a width of about 10 centimeter (3.9 in), you're ready to enter the second phase of labor. You may begin to feel an urge to push, but your attendant will usually tell you not to do so until your cervix has dilated to 10 centimeter (3.9 in). At this point, it is usually not too late to receive pain medication. If you have planned for this possibility and have painkillers on hand, talk to your doctor or midwife to assess whether they are appropriate.

Follow your attendant's instructions for pushing. In the second stage of labor, your contractions will become more frequent and more intense. Pain will increase. You may feel a strong urge to push: if your cervix is fully dilated, your birth attendant will give you the OK to do so. Communicate with your doctor or midwife, notifying them of any changes in your condition. They will instruct you when to push, how to breathe, and when to rest. Follow these instructions as well as you are able. This stage of labor can last up to 2 hours for first-time birth givers, while in subsequent deliveries this stage can be far shorter (sometimes as short as 15 minutes). If you're not fully dilated, wait for your go-ahead. Don't be afraid to try different positions, like getting on all fours, kneeling, or squatting. Your doctor or midwife will usually want you to be in the position that is most comfortable and allows you to push most effectively. As you push and strain, don't worry about accidentally urinating or defecating - this is extremely common and your birth attendant will expect it. Concentrate solely on pushing out the baby.

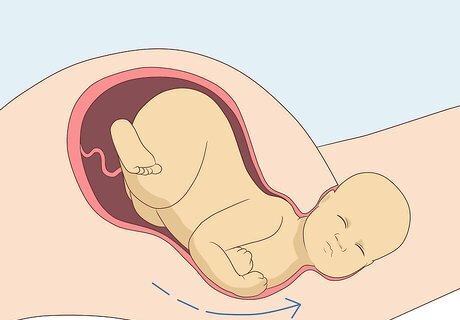

Push the baby through the birth canal. The force of your pushing, combined with your contractions, will move your baby from the uterus into the birth canal. At this point, your attendant may be able to see the baby's head. This is called "crowning"—you can use a mirror to see it yourself. Don't be frustrated if, after crowning, the baby's head disappears—this is normal. Over time, the baby's position will shift down the birth canal. You'll need to push hard to get the baby's head out. As soon as this happens, your birth attendant should clear the baby's nose and mouth of any amniotic fluid and assist you in pushing the rest of the baby's body out. Don't be afraid to scream, cry, wail, or groan. This is very common during contractions and birth pains. Breech birth (when a baby's feet come out before their head) is a medical condition that carries added risks for the baby and will most likely necessitate a trip to the hospital. Most breech births today result in C-sections.

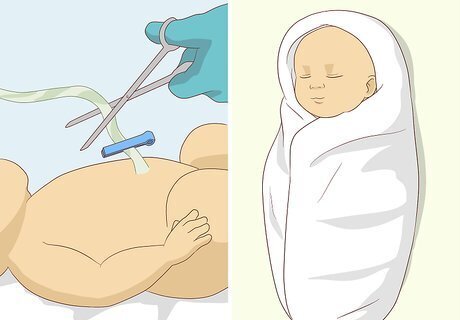

Care for the baby after birth. Congratulations—you have just had a successful home birth! Have the doctor or midwife clamp and cut the baby's umbilical cord using a sterile pair of scissors. Clean the baby by wiping them with clean towels, then clothing them and wrapping them in a clean, warm blanket. After giving birth, the birth attendant may recommend initiating breastfeeding. Do not bathe the baby immediately. At birth you will notice the baby has a whitish covering. This is normal—the covering is called a vernix. It is thought to provide protection from bacterial infections and moisturize the baby's skin.

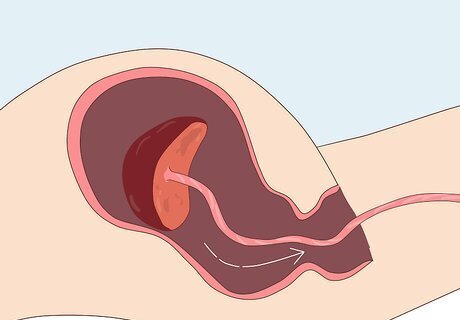

Deliver the afterbirth. After the baby is born, though the worst is over, you aren't quite done. In the third and final stage of labor, you must deliver the placenta, which is the organ that nourished your baby while it was in the womb. Mild contractions (so mild, in fact, that some people don't notice them) separate the placenta from the uterine wall. Soon after, the placenta passes through the birth canal. This process usually takes about 5-20 minutes and, compared to delivering a baby, is a relatively minor ordeal. If your placenta doesn't come out or doesn't come out in one piece, go to the hospital. This is a medical condition that, if ignored, can have potentially serious consequences.

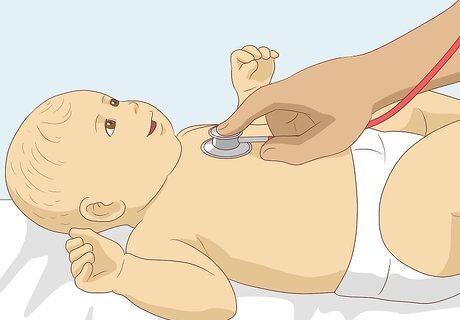

Take your baby to a pediatrician. If your baby appears perfectly healthy after birth, they probably are. However, it's important to take your new child to a doctor for a medical examination within a few days of birth to make sure they aren't suffering from any medical conditions that can't easily be detected. Plan a visit to a pediatrician within 2 or 3 days after giving birth. Your pediatrician will examine your baby and give you care instructions. You may also want to receive a medical examination yourself—childbirth is an intense, demanding process, and if you feel out of the ordinary in any way, it's best to have a doctor determine whether anything is wrong.

Understand the pros and cons of water births. Water birthing is exactly what it sounds like—giving birth in a pool of water. This method of birth has become more popular in recent years—some hospitals even offer birthing pools. However, some doctors don't consider it to be as safe as conventional birth. While some people swear by water births, claiming that it's more relaxing, comfortable, pain-free, and "natural" than normal birth methods, it does carry certain risks, including: Infection from contaminated water Complications from the baby swallowing water Though very rare, there is also a risk of brain damage or death from oxygen deprivation while the baby is underwater.

Know when a water birth is inappropriate. Like any home birth, water births shouldn't be attempted if the baby or parent are at risk for certain complications. If any of the conditions listed in Part One apply to your pregnancy, do not attempt a water birth—instead, plan to go to a hospital. Additionally, you shouldn't attempt a water birth if you have herpes or another genital infection, as these can be transferred to the baby via water.

Prepare a birth pool. Within the first 15 minutes of labor, have your doctor/midwife, your partner, or a friend fill a small pool about a foot deep with water. Special pools designed specifically for water births are available for renting or purchase—some forms of medical insurance will cover the cost.

Enter the pool when your cervix is dilated at least 4 centimeters (). Wait to enter the pool until your cervix is dilated 4 centimeters or more. If you enter the pool sooner, it may slow labor down. Take your clothing off below the waist (you may choose to be completely nude if you prefer) and enter the pool. Make sure your water is clean and no hotter than 100 degrees Fahrenheit (about 37 degrees Celsius).

Have a partner or birth attendant enter the pool with you (optional). Some people prefer having their partner in the pool with them while they give birth for emotional support and intimacy. Others prefer to have their doctor or midwife in the pool. If you plan on having your partner in the pool with you, you may want to experiment with leaning back on your partner's body for support as you push.

Proceed through labor. Your doctor or midwife will assist you through your labor, helping you breathe, push, and rest when it's appropriate. When you start to feel the baby coming, ask your doctor/midwife or partner to reach between your legs so they will be able to grab the baby as soon as they come out. You will want to have your hands free to hold on tight when pushing. As with normal labor, you may change your position for comfort. You may, for instance, try pushing while lying or kneeling in the water. If, at any point, you or the baby show any signs of complications, get out of the pool.

Get the baby above water immediately. As soon as the baby is out, hold them above water so that they are able to breathe. After momentarily cradling the baby, carefully get out of the pool so that your cord can be cut and the baby can be dried, clothed, and wrapped in a blanket. In some cases, the baby will have their first bowel movement in the womb. In this case, get the baby's head above water and away from any contaminated water immediately, as serious infection can occur if the baby inhales or drinks any feces. If you believe that this may have happened, take your baby to a hospital immediately.

Comments

0 comment