views

Does the speech resonate?

Look for signs the speech is tailored to suit its target audience. This means that elements like the word choices, references, and anecdotes should make complete sense to the people listening to the speech. For example, an anti-drug speech aimed at first graders should sound very different from one meant for college students! Put yourself in the target audience’s shoes and determine whether the speech hits the mark. If possible, note audience reactions to the speech. Do they seem to understand it? Are they paying close attention or getting bored? Remember to view the speech from the perspective of the target audience, which can be a bit tricky if you’re not actually in the target audience. Use your best judgment.

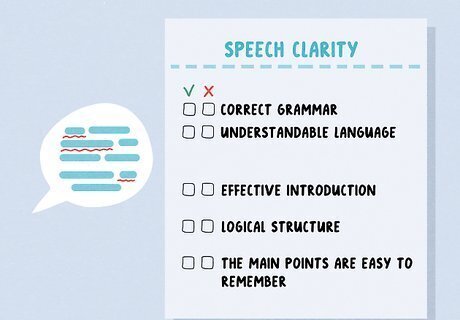

Is the speech easy to follow?

The speaker should utilize a structure that’s clear, organized, and logical. Focus intently on what the speaker is saying. Do they make the subject of the speech clear quickly, perhaps after a brief anecdote or two, then build from there in a smooth and understandable fashion? To decide if the speech is easy enough to follow, consider questions like the following: Is the introduction effective? Does the speaker make their primary argument apparent within the first few sentences, or does it take awhile before you figure out what they are getting at? Is the speech full of distracting tangents that do not relate to the primary topic, or does it build in a logical manner toward the conclusion? If you were to summarize the speech to someone else, could you recite all the main points or would you have trouble remembering what it was really about?

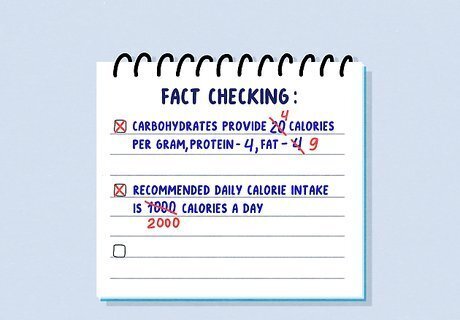

Is the speech convincing?

Keep track of the speaker’s use of persuasive evidence and analysis. Does the content of the speech demonstrate the speaker’s expertise on the subject? If so, the audience will come away feeling they learned something new—even if they don’t necessarily agree with every point! Look for gaps in the speaker’s reasoning or places where further research would have made the speech more convincing. Listen for clear evidence (like names, dates, statistics, and other data) that backs up the points the speaker is making. Take notes so you can do some fact-checking to make sure the evidence is accurate. Once you’ve evaluated the quality of the evidence, make sure it supports the arguments and analysis made in the speech. A truly convincing speech has to hit on both elements—solid evidence and strong analysis.

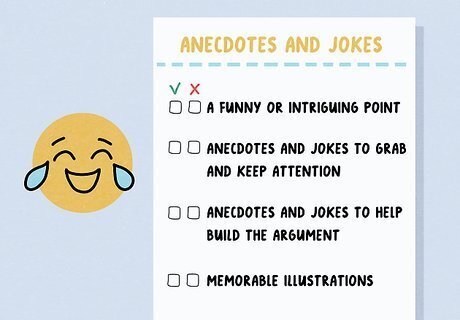

Is the speech entertaining?

Yes, the speaker should have “personality,” but so should the speech itself. Anecdotes and the occasional joke break up the serious tone of the speech and keep it from getting boring. If the speech is too dry, even the most convincing argument will land with a thud on a bored, distracted audience. When deciding if the speech is engaging at a high level, ask questions like these: Does it start with a good hook? Good speeches usually start with a funny or intriguing point that draws the audience in. Does it stay engaging the entire time? Well-placed anecdotes and jokes can grab and keep listeners' attention. Are the anecdotes and jokes distracting, or do they help build the speaker’s argument? Does the speaker use examples judiciously? One really superb, memorable example is better than three that don't stick with the audience.

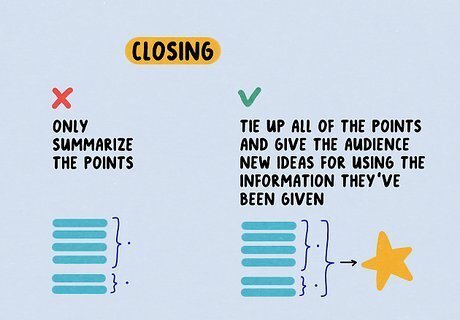

Does the speech have a strong closing?

See if the speaker ties things up and really hits home with the audience. The first impression a speech makes is critical, but the last impression may be even more important! A strong closing should tie up all of the main points and give the audience new ideas for using the information they've been given. A poor closing will only summarize the points, or outright ignore them and go on to a topic that has nothing to do with what the speaker has been saying. It’s natural for the audience’s focus to lag as the speech carries on, so the closing should regain their attention by being powerful, thoughtful, deep, and concise. Both the speech and the speaker should exude confidence during the conclusion. This helps the audience gain confidence in the presentation.

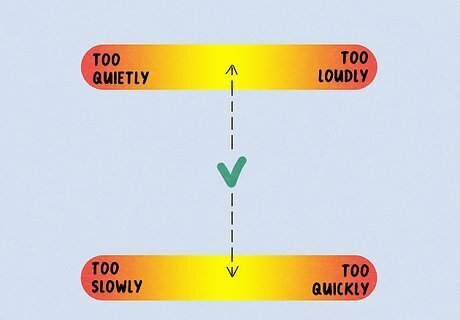

How is the speaker’s vocal delivery?

They should talk in a way that makes you want to keep listening, not tune out. Watch for instances of the “little things” a good speaker does to hold their audience’s attention. Do they, for example, pause for effect at the right time and speak at the proper tempo and volume? Keep the following in mind as you listen: A person who is speaking too loudly may seem aggressive, while one who is speaking too quietly may struggle to be heard. See if the person seems to have a good sense of how loudly to speak. Many speakers tend to speak too quickly without realizing it. See if the person is speaking at a pace that sounds natural and easy to understand. Well-placed and well-timed pauses help the audience digest what’s just been said and prepare for what’s about to be said. Pauses that are too short or non-existent don't give the audience these opportunities, while pauses that are too long are distracting.

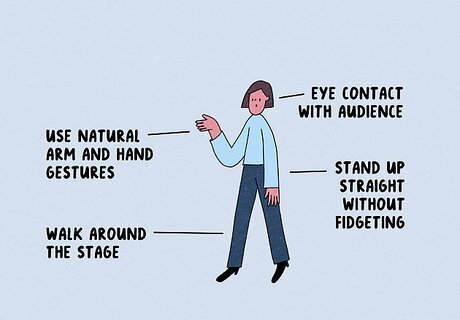

How is the speaker’s body language?

Their eye contact and mannerisms should project confidence and charisma. A speaker’s body language can go a long way toward making the audience feel engaged and included—or, instead, bored and detached. Someone who’s less skilled at public speaking might look down at their feet, fail to make eye contact, and fidget nervously, while a talented speaker will do the following: Make easy, natural eye contact with audience members scattered throughout the crowd. This helps every part of the audience feel included. Stand up confidently, but not stiffly, and without fidgeting too much. Use natural arm and hand gestures from time to time, especially to emphasize key points. When appropriate, walk around the stage in a confident but relaxed manner instead of staying behind the podium.

Is the speaker showing high anxiety?

Public speaking fear is very common, but good speakers learn to control it. Surveys often rate fear of public speaking above fear of death, so it’s definitely the real deal! Even great public speakers usually feel nervous energy on the inside, but they’ve learned to channel that energy into an engaging stage presence. Look for signs that the speaker is nervous so you can offer a constructive critique that will help them improve next time. Note any repeated movements or gestures that take away from the content of the speech; these could be signs of nervousness. A shaky voice or tendency to mumble are also signs of nervousness. Filler words like “ums,” “likes,” and “uhs” can take away from a speaker’s credibility, since they make them sound a bit unprepared. While saying a few filler words is natural, they should not overwhelm the speech.

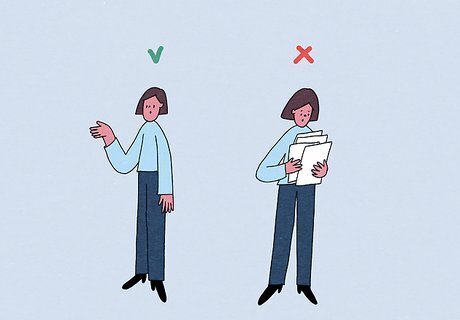

Did they read, memorize, or master the speech?

A great speaker won’t just memorize their speech—they’ll master it. It should never look or feel like the speaker is reading their speech. While briefly checking a page of notes or the current PowerPoint slide is fine, the speaker shouldn’t have their eyes glued to their notes. But they also shouldn’t have memorized the speech word-for-word and recount it in a stiff and robotic way. Instead, they should have memorized the content and “spirit” of the speech so well that it flows out naturally and full of personality. Mastering the speech allows the speaker to better engage with the audience and make adjustments “on the fly” without wrecking the speech’s flow.

Take notes during and after the speech.

Jot down your observations in real time, then expand on them after. Use a notebook and pen (or your preferred digital device) to make note of the strengths and shortcomings of both the speech itself and the speaker’s delivery. Consider dividing your notes into two sections: one for quick notes on the speech’s content and one on the speaker’s delivery. Expand on these notes as soon as possible after the speech so you’re able to create a detailed critique that can truly benefit the speaker. Instead of a blank notebook, you may instead want to jot down several key questions or areas of focus (like those listed in this article) as a checklist you can refer to during the speech. Make sure to also take notes to flesh out your checklist, though. If there are no restrictions against it and you have time, record video or just audio of the speech. Always get the permission of the speaker first.

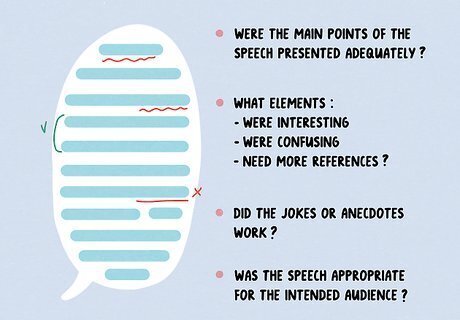

Critique the speech’s content first.

Evaluate each major section of the speech, then the speech as a whole. Go in order, starting with the introduction and ending with the conclusion, and judge the effectiveness of each component. Then, give an overall evaluation of whether the main points of the speech were adequately presented and reinforced, and whether the speech as a whole was convincing and credible. Clearly state whether the speech was successful as-is or, if not, which areas could benefit from revisions. Note which elements of the speech were interesting, which parts were confusing, and which areas need more references to back them up. Identify jokes or anecdotes that either really hit the mark or just didn’t work. It’s better to be honest now than to let the person tell the same bad joke twice! Note whether you felt the speech was appropriate for the intended audience.

Critique the speaker’s delivery second.

Provide feedback on things like vocal tone, eye contact, and body language. Critiquing the delivery of a speech can be more awkward than evaluating its content, but it’s also the kind of feedback that speakers often benefit from the most. Run through an honest and constructive analysis of the effectiveness of the speaker’s delivery, going piece-by-piece through areas like tone of voice, speaking volume, pacing, eye contact, mannerisms, and posture. Finish with an overall evaluation of the speaker’s delivery. If, for example, the speaker seemed really nervous, it’s important to point this out as a distracting element that blunted the impact of the speech. You might also constructively point out techniques that help reduce stage fright, like exercising before the speech, laughing before the speech, and practicing in front of a small group of people first.

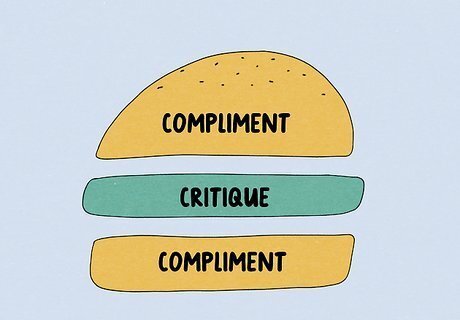

Offer positive encouragement throughout.

Don’t just point out negatives—highlight good points and tips for improvement. No matter if you’re evaluating a professional orator or a school classmate, your critique should be constructive. While that means you need to point out what went wrong, it also requires that you identify what went right and offer suggestions for improvement. That said, if you’re working with a student or someone who needs help improving their speech-giving skills, be extra encouraging in your critique so they have the confidence to keep working on their skills. Try the feedback sandwich technique: give the person a compliment on an element of their speech, tell them what needs improvement, then give them another compliment. For example, tell them they started with a brilliant hook, then explain that the second point was confusing, and finish by noting how the conclusion clarified the main point. As a way to encourage the person to keep learning and improving, you might suggest they watch videos of speeches given by famous speakers. Point out similarities and differences between the speech you’re critiquing and the famous speech.

Comments

0 comment