views

- Use a dream sequence to push the story forward in some way—for example, by shedding light on a character's fears or desires, or foreshadowing future events.

- Employ logic in your dream sequence, but try not to be too logical: dreams tend to be surreal and vivid and often don't make much sense upon waking.

- Use symbolism in the dream to express a character's complex abstract thoughts, fears, or desires in concrete and compelling ways.

How to Write a Compelling Dream or Nightmare

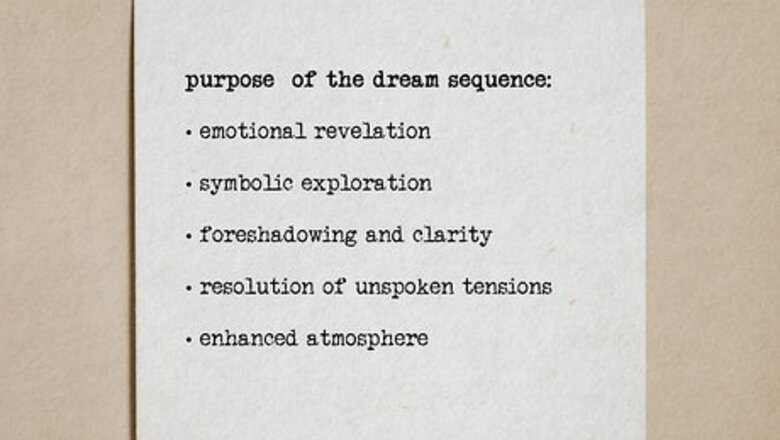

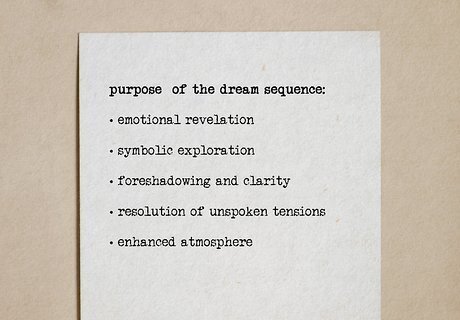

Make sure your dream has a purpose for the novel. Dreams are weird—but weirdness alone is not usually enough of a reason to include a dream sequence in your novel. If your character’s dream doesn’t have something to do with the plot or their character development, you run the risk of your reader becoming bored or confused (or both). As you craft your dream, think about what it contributes to the overall narrative. You may not know from the get-go what your dream sequence contributes. This might be something you figure out as you write (and rewrite and re-rewrite) your story, so don’t feel pressure to know everything before you’ve even begun writing.

Be logical…but not too logical. Think about your own dreams: they make sense while you’re in them…but once you’ve woken up again, you can’t remember how they made sense. While many readers will appreciate being able to follow the narrative of your dream sequence, consider adding some “dream logic” to the scene to give it that surreal quality most real-life dreams have. For example, while in real life, you might walk to the fridge to get an apple, in a dream, the apple might suddenly appear in your hand, or you might find it in the closet and not think anything of it.

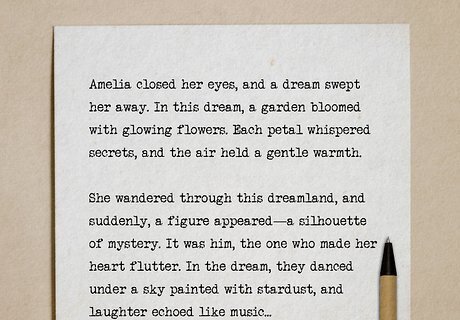

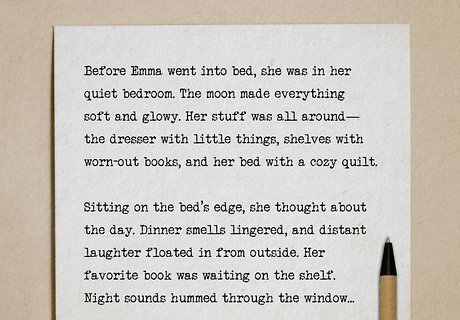

Use vivid imagery. Even the most bizarre and illogical of dreams can be as vivid as waking life—sometimes even more so. Don’t be afraid to use lots of descriptive imagery to really give readers an idea of what is going on in the dream. Note that using vivid imagery doesn’t mean over-describing—a few well-selected words can paint a more vivid picture than 100 poorly-chosen ones.

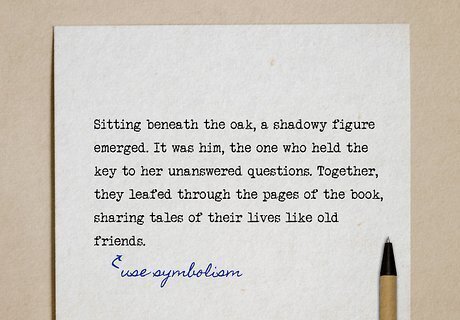

Employ symbolism. If you’re a Freudian, everything in a dream is meaningful. Everything. Even if you’re not into Freud, symbolism is an effective tool for conveying a deeper message in a work of art: by representing an abstract thing with something concrete, you can more easily and satisfyingly convey complex ideas to your readers (without beating them over the head with the answer). Ask yourself if what you’re writing needs to be in dream form, or if it could (or should) just be included in the actual plot: when the events in your character’s dream are just how they would appear in waking life, it begs the question—why are they dreaming it instead of experiencing it in waking life? For instance, your character might fear death in their day-to-day life, but in a dream, instead of having them or someone close to them die, you might represent their fear with a giant black cement block looming over them or a shadowy closet or something else totally ominous that helps the reader better understand their anxiety.

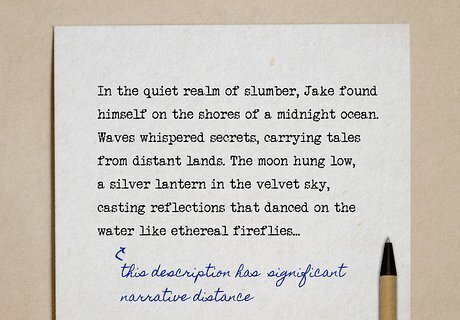

Consider using narrative distance. Narrative distance refers to how closely the narration reflects the character's thoughts and feelings. No narrative distance means readers get clear insight into how a character is feeling or what they're thinking at a given moment, but significant narrative distance will give a scene a less certain, more mysterious atmosphere—perfect for creating a dreamy vibe. Narrating the book in the character's vernacular and expressing every thought and emotion clearly would be an example of almost no narrative distance. On the other hand, a narrator who offers almost none of the character's subjective thoughts or feelings, and only describes the character's actions in objective terms, creates significant narrative distance. While prescriptivists might argue you need to maintain the same amount of narrative distance throughout a story, as long as you have a clear purpose for changing the narrative distance, it can be extremely effective.

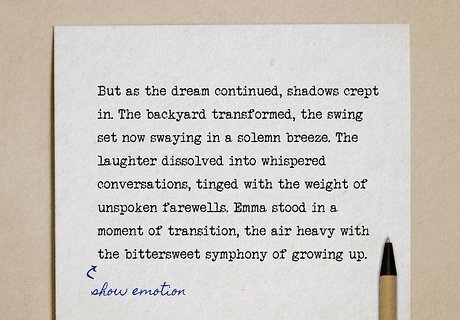

Express emotion. Because dreams are where your character’s unconscious lives, they give you an opportunity to explore your character’s underlying emotions in greater depth than you might be able to in their waking life. So take advantage of this! How do they feel about whatever strange, scary, beautiful, sad, happy, or straight up confusing events are happening in their dream (or nightmare)? Just telling us what happens in the dream might be vaguely interesting (“I floated up to the ceiling and then a sentient cheese puff told me I was going to die”) but unless readers get a sense of how your character feels about what’s happening, they may write off the whole scene as unimportant—or worse, a waste of time.

What are dream sequences in novels for?

They push the story along. As a general rule of thumb, if your dream doesn’t reveal any new information to the reader, then it might not be worth including in your book. The most effective dream sequences offer something that the reader couldn’t get from your character’s waking life—a realization on the part of the character, an understanding of your character’s motivations, a glimpse of past events that influence your character’s present, etc.

They foreshadow events to come. Dreams are wonderful ways to subtly predict what’s going to happen later in a novel. However, foreshadowing is a delicate art: if your hints about what’s to come aren’t subtle enough, the reader will pick up on them too easily, spoiling the narrative. On the other hand, when foreshadowing is done deftly without being too obvious, it can make the narrative as a whole feel more cohesive and thoughtful. For example, in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Jane is told that dreaming of a child is a bad omen; the more time she spends in Mr. Rochester’s mysterious house and the closer she comes to a precarious romance with him, the more she herself dreams of children—hinting to the reader (as well as to Jane) that there is trouble ahead.

They showcase a character's fears or desires. Dreams can reveal a lot about your character’s motivations and internal conflicts, including what they’re most afraid of and what they most long for. After all, dreams are where our unconscious lives and runs wild: things your character might not actively pursue or talk about in their waking life, they may dream about. This way, your readers can get a better, more honest sense of who your character is and what motivates them. For example, if your character’s marriage is suffering, you might have them dream about their partner having no face or substitute their dream-partner with another person or thing to illustrate that they feel distant from them or as if they don’t know them anymore.

They help a character realize something. Part of what makes good characters believable is that they aren’t perfect: they might not see things happening right under their nose, or they might not realize they’re acting in ways they shouldn’t. They might not know themselves very well. Dreams are an effective way to show the reader what’s happening in a character’s mind and guide the reader toward deep-seated truths they hadn’t been able (or hadn’t wanted) to recognize before.

Types of Dream Sequences

Nightmares If you want to illustrate your character’s fears, a nightmare is the perfect way to do it. Nightmares are horrific at their most extreme and unsettling at their subtlest, but any “level” of nightmare can help your character confront their deep-seated fears and worries. You might even opt to give your character hypnopompic hallucinations: visual, auditory, or tactile hallucinations experienced as a person is waking up. Giving your character sleep paralysis can add an extra layer of horror: sleep paralysis is just a temporary loss of muscle control after falling asleep or waking, but it can be quite alarming for the sleeper and often involves hallucinations or the sensation of being suffocated.

Lucid dreams In most dreams, you’re probably not aware that you’re dreaming—until you wake up and realize it was all in your head. In a lucid dream, however, the dreamer is aware that they’re dreaming and may even be able to control what they do in their dream, to some extent. You could give your character a lucid dream as a way to show what would happen if they had their way in real life: what would they do? How would others react?

Fantasies Because dreams often showcase our deep-seated fears and desires, dream sequences are a great method of exploring your character’s wildest fantasies. What do they crave more than anything? If they had their way, how would your novel end?

Recurring dreams If your character suffers from unresolved issues, such as PTSD, recurring dreams may be a useful way to showcase this. You might choose to narrate the same dream over and over again, or you might adopt small (or significant) changes from dream to dream that say something about the character’s progress overcoming their unresolved issues.

Linked dreams Looking to add a supernatural element to your novel? Having two different characters share the same dream or be able to communicate in dreams can be a compelling way to illustrate a link between the characters or even to move the plot forward within the confines of “dreamland.” You might even have your character connect with someone who has passed on: maybe they receive guidance from their deceased mother, for instance.

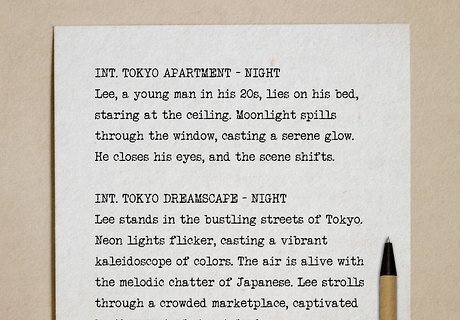

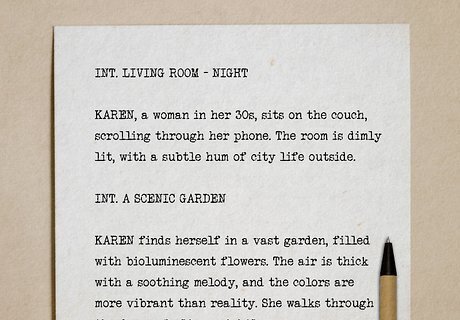

How to Format a Dream Sequence

Make it clear that it’s a dream. Indent the text, write the dream scene in a different font, or put the dream in italics: “I light a candle and it turns into a human head.” You may also opt to keep the formatting the same throughout, but explicitly indicate that the character is dreaming, as J. K. Rowling does in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets: "He dreamed that he was on show in a zoo, with a card reading UNDERAGE WIZARD attached to his cage."

Keep the formatting the same if you want to leave readers uncertain. In some cases, you might not want readers to know it’s a dream or want their grip on the novel’s reality to be more shaky. In this instance, avoid formatting the dream in a way that signifies it's not part of the character's waking life. An example of a novel in which the reader is by design uncertain which scenes are really happening and which are merely dreams, fables, or the character’s imagination is Kate Bernheimer’s The Complete Tales of Ketzia Gold.

Comments

0 comment