views

- Start with a strong opening move to set the stage for a winning game.

- Plan 4-5 moves in advance to stay ahead of your opponent. Focus on setting up future attacks or traps.

- Evaluate every possible move you have before you make it. Make the best possible move at every turn.

Winning As a Beginner

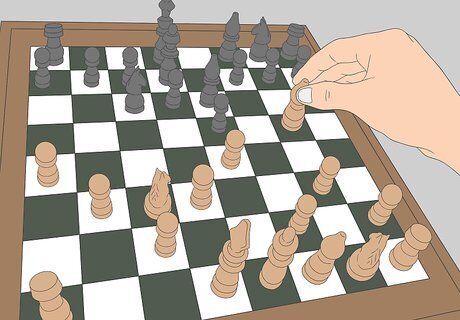

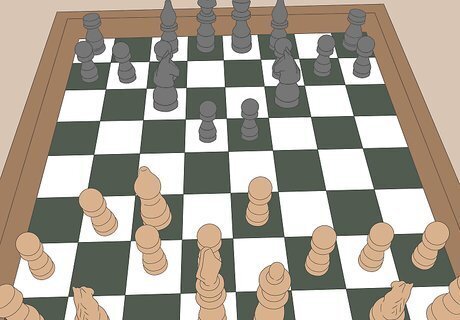

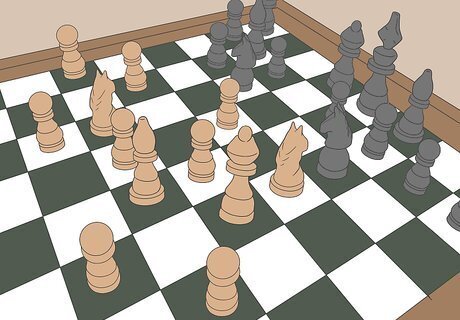

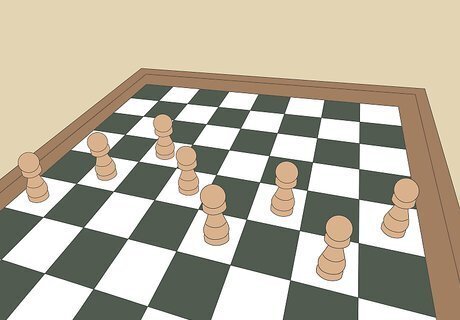

Understand the goals of a good opening move. Chess openings are the first 10-12 moves in the game, and they will determine your general strategy and positioning for the entire match. Your goal in the opening is to develop or move off the starting squares as many strong pieces as possible. There are several key considerations in a good opening: Move your pawns toward the center of the board while opening up your stronger pieces for easy movement. The most common yet very efficient path would be to move the king's pawn 2 spaces forward (e4 for White, e5 for Black) and then the queen's pawn forward 2 spaces (d4 for White, d5 for Black), if it is not at risk after the opponent makes their move. This formation allows you to develop bishops, increases castling speed, and forms a defensive but less offensive fortress with the right moves. Your opening moves will also be dependent on whether you are Black or White. Since White moves first, you'll want to move in on the attack and try and control the game. Black should hold back and wait a bit more, letting White expose themselves with a mistake before attacking. Never move the same piece twice unless it could get in trouble and be taken. The more pieces you move, the more your opponent needs to react to you. Don't make too many pawn moves. The goal of a good opening is to develop your major pieces efficiently, and moving too many pawns can give your opponent a tempo advantage. Try not to move the queen out too early. Many beginners make the mistake of moving their queen out early, but this can leave your queen vulnerable to attack, causing you to have to move it again and lose a tempo. Keeping these principles in mind, check out the list of opening moves used by Grandmasters at modern tournaments.

Think 4-5 moves in advance, using each move to set up more complicated attacks. To win at chess, you need to be constantly thinking a few moves in advance, setting up longer, more complicated attacks to outfox your opponent. Your first move is about setting up the rest of the game, leading to your first attack or controlling certain sections of the board. The best way for a beginner to learn how to plan ahead is to practice some common openings: The Ruy Lopez is a classic opening to get bishops out and attacking. Move your king's pawn up two spaces, then your knight up f3 (as White). Finish by pushing your king's bishop all the way until it is one space in front of the opponent's pawn. The English Opening is a slow, adaptable opening. Move the c2 pawn up 2 squares (c2-c4), then follow with the g2 pawn (g2-g3) to free your king's bishop (if Black moves to the center) or the queen's knight, (if Black moves along the sides). Try the adventurous King's Gambit. Used by grandmasters from Bobby Fisher onward, this exciting opening can put beginners off-balance early. Simply move both king pawns (e2 and f2) up two spaces with the opening move. Black will frequently attack early, feeling like they have you opened up, but your pawn wall will quickly cause them problems. Try the Queen’s Gambit to control the center of the board. White moves the queen’s pawn to d4, drawing out Black’s pawn to d5. White typically retaliates with bishop’s pawn to c4. This maneuver brings the game out to the center and opens up the lanes for your queen and bishop to move. A good defense to a Queen’s Gambit is the Queen's Gambit Declined. After the opening moves, start by moving your king’s pawn to e6. You’ve now opened up a path for your bishop to attack. If he moves their knight to c3, you can move your bishop to b4, pinning the knight.

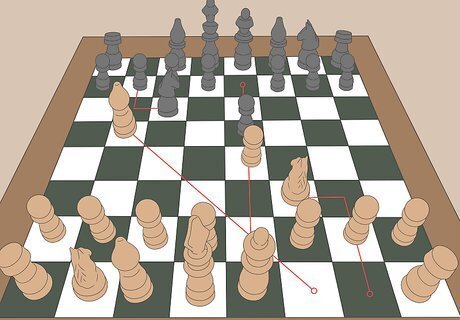

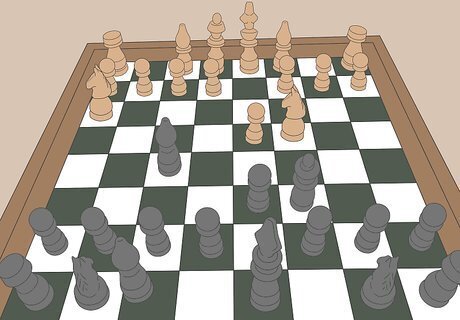

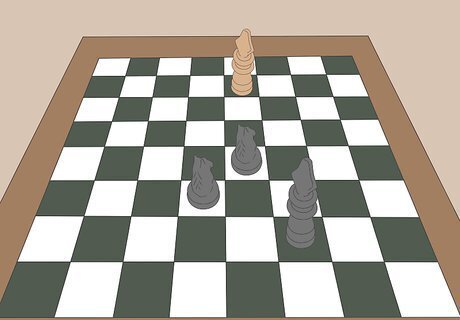

Try out the four move "Scholar's Mate" to win the game almost instantly. This trick only works once per player, as a savvy chess player will spot the move and get out of the way. That said, Scholar's Mate is a great way to catch a beginner opponent off guard and snag the game from them quickly. As White: king's pawn up 1 (e2-e3); king's bishop to c4; queen to f3, queen to f7. As Black: king's pawn moves up 1 (e7-e6); king's bishop to c5; queen to f6; queen to f2. Countering Scholar's Mate: Pull your knights out as blockades if you see Scholar's Mate happening—chances are good they won't sacrifice a queen just to take your knight. The other option is to use a nearly identical move, but instead of pushing your queen up, leave her back on e7, in front of your king.Warning! Scholar’s Mate usually only works when your opponent is a beginner, as they’re still new to chess and might not spot your plan. It's not advised to move the queen out early in most cases and many players will use that to their advantage.

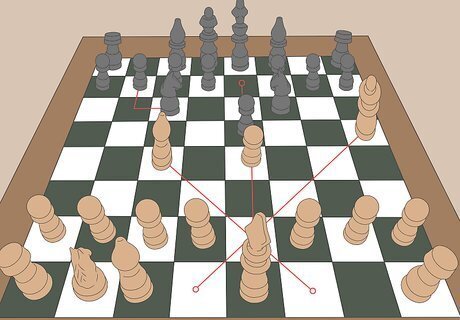

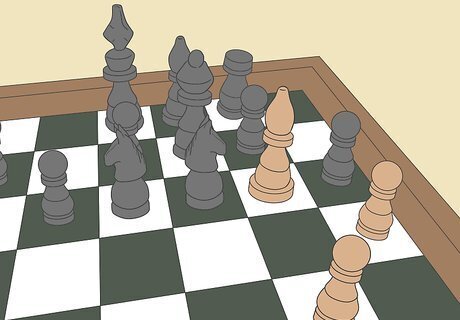

Control the center squares to control the game. Your biggest concern is controlling the center tiles, specifically the four in the very middle, when playing chess. This is because you can attack anywhere from the center of the board, allowing you to control the game's pace and direction. For example, the knight has eight potential moves in the board's center, but only 1-2 on the edges. There are two general ways to do this. Supported Middle is when you move slowly into the center of the board with several pieces. Knights and bishops support from the fringes, able to move in and take pieces if you get under attack. In general, this slow development is more common. Using the Flanks is a very modern style of play that controls the middle from the outsides. Your rooks, queen, and knights run up both sides of the board, making it impossible for your opponent to move into the middle without being taken.

Develop as many pieces as you can. Once you’ve made the opening moves, it’s time to start developing an attacking position. You want to give each of your pieces the best possible square to move to, getting pieces off of the starting squares. Unless you are forced to, the best method is to move your pieces in turn. Don’t move the same piece twice unless you must defend it from an unexpected attack or make a vital attack. Do not count pawns as pieces during an opening. Moving all your pawns out will only make your more valuable pieces vulnerable to capture and can potentially open you up to checks and checkmates. Save your pawn moves for the endgame. Counterintuitively, your king is "developed" by castling. This moves your king into the corner of the board in a place where it is far less likely to be put in check. It also moves one of your corner rooks closer to the center.

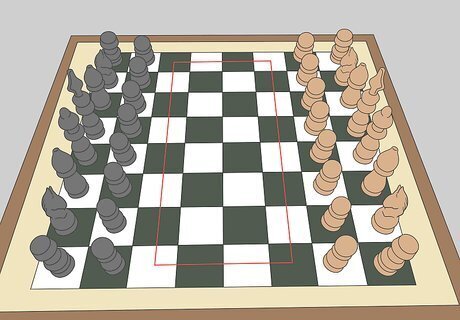

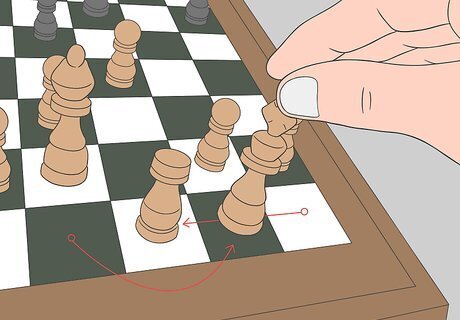

Learn to castle. Castling is when you move the king over a rook, effectively using the rook to form a wall against attack. Above the king, you still have a line of pawns protecting you as well. This is an incredibly effective tactic, especially for beginners learning the game. To do it: Clear the path between your king and rook by moving the bishop and knight (and potentially your queen). Try to keep as many pawns as you can in place. You can do this on either side. Move your king two squares to the right or left, then cross the rook over your king. The end result is that your king is on the G or C file, and your rook is on the D or F file, for kingside and queenside castling, respectively. Note that the king and the rook cannot have moved once before castling. If they do, the move is no longer allowed. You also cannot castle into check, through check, or out of check. You cannot make any move that puts your king into check, including castling, but you also cannot castle if you are currently in check. Finally, you cannot castle if your king will cross through a square that would put your king into check, even if that square is not the destination square. You can also castle queenside. Clear the queen, queen's knight, and queen's bishop out of their starting squares. Then, move your king two spaces and move your rook directly to the king's right in one move. In a chess tournament setting, make sure to move your king first, then the rook. If you move the rook first, that'll count as one rook move, and not a castle. Part of what helps you win at chess is your ability to read your opponent without letting them read you. Don’t begin your move until you are sure it is the right move. You want to be thinking several moves ahead at all times. This means knowing where each of your pieces can move in any situation and predicting how your opponent will react to your moves. This skill isn’t always easy to gain and will take practice.

Understand the value of each piece and protect them accordingly. Obviously, your king is the most important piece on the board, since you lose if it's taken. However, the rest of your pieces are not easily dispensed cannon fodder. Based on the math and geometry of a chessboard, certain pieces are more valuable than others. Remember these rankings when taking pieces. You do not, for example, want to put a high-value Rook at risk just to take an opponent's knight. Pawn = 1 point. Knight = 3 points. Bishop = 3 points. Rook = 5 points. Queen = 9 points. Chess pieces are sometimes referred to as "material." Having a material advantage going into the endgame can give you much better chances of beating your opponent. Most of the time, the bishop is stronger than the knight. However, there can be exceptions.

Winning As an Intermediate Player

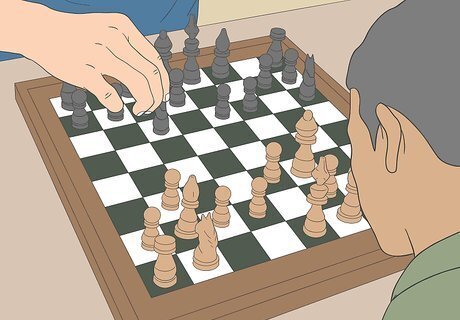

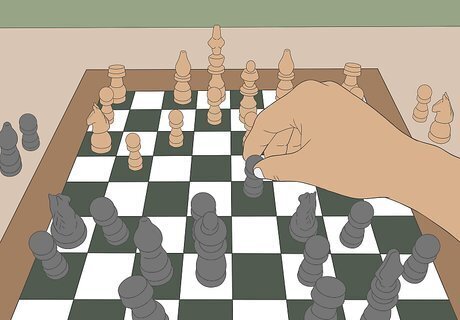

Oversee your opponent's moves. What pieces are they developing, and what sides of the board are they favoring? If you were them, what sort of long-term strategy would you be planning? Once you have the basics of your own play down, you should constantly adjust to your opponents. If he's holding back, setting up pieces near her side for an attack, ask yourself what her end-goal is. Are there ways you can disrupt or put their plan on hold? Does he have the advantage, and do you need to fall back and defend some units to prevent a serious loss of material, or can you put some pressure on them?

Know when to trade pieces. Trading pieces is obvious when you end up with the material advantage, such as giving up a knight to get their queen, but it is much trickier when trading off similar pieces. In general, you do not want to trade pieces when: You have the advantage in position, center control, and development. The fewer pieces are on the board in total, the less of an advantage you have and the easier you can defend against. The opponent is cramped or stuck in a corner. When you have them locked in, it is more difficult for them to move or maneuver many pieces, but fewer pieces can get them out of the jam and free again. You have fewer pieces than your opponent. If you have more pieces than them and the advantages are otherwise similar, start taking pieces. You'll open up new attacking lanes. You would double-up pawns. A doubled pawn is when you have one pawn in front of the other. This makes them both much less useful and clogs up your side of the board. However, if you can make your opponent double pawns as a side-effect of an even trade, this could be a useful move. You're trading a bishop for a knight. In general, bishops are better than knights. There are many exceptions to this, though, so you have to take into account the situation.

Develop 5-6 moves in advance every time. It is easier said than done, but you need to be thinking long-term to win chess games with any regularity. Each piece you move should be done with three common goals in mind. If you keep these points in your head, you'll find you can easily start improvising multi-move plans to win the game: Develop multiple pieces (rooks, knights, queen, bishop) early and often. Get them out of their starting spots to open up your options. Control the center. The center of the board is where the action happens. Protect the king. You can have the best offense in the world, but leaving your king open is a sure-fire way to lose at the last minute.

Hold your advantage until you can get the most out of it instead of rushing in. Chess is about momentum, and if you have it, you need to keep it. If your opponent is purely reacting to you, moving pieces out of the way frequently and unable to mount an attack, take your time and whittle them down. Remember, you can win a match-up and still lose the game. Don't move in if you're opening up to a counter-attack. Instead, pick off their defending pieces, take full control of the middle of the board, and wait to hit them until it really hurts.

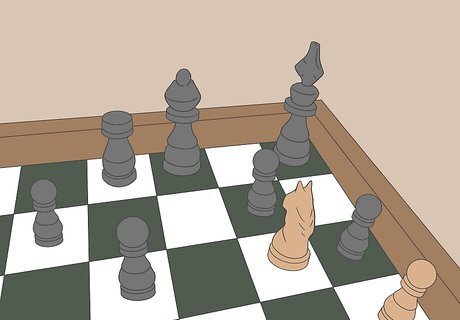

Learn to pin pieces. Pinning is when you "trap" a piece such that it cannot move without leaving a more valuable piece open to attack. This passive sort of warfare is a great way to control the game, helping you master your opponents. To do it, look where a piece can move. Usually, pieces with limited options are your best bet. Then, instead of attacking, position your piece so that you could take them no matter where they move, effectively making the piece useless for a period of time. A pin where the king is the more valuable piece behind the pinned piece is an absolute pin. The pinned piece can't move at all. A pin where a more valuable piece other than the king behind the pinned piece is called a relative pin. The pinned piece can move but at the cost of a more valuable piece. A pin where a piece isn't behind the pinned piece is called a situational pin. The pinned piece can't move due to leaving a resource open to the opponent (tactic, attack, files, etc.). Sacrifices are when you allow your opponent to take your piece. The only catch is knowing that you can take their piece right back. They may take it, and they may not—the important thing is that you're in control.

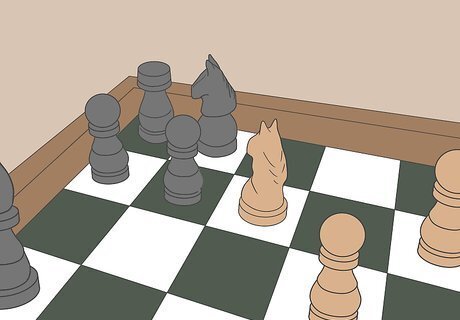

Learn to fork pieces. A fork is a move in which a piece attacks two or more pieces at once .Planning and executing a fork is a great way to win material and put yourself at an advantage. For example, if you fork the king and the queen, the opponent will have no choice but to give up their queen, giving you an advantage that is normally enough to win the game. When attempting a fork, keep the following things in mind: Forking is most easily done with the knight, as its unusual movement lets it attack multiple pieces hidden behind others. Try to fork the most valuable pieces. The best possible fork is the fork of the king and queen. This is called a royal fork. A fork is most effective when it forces your opponent to react to it immediately, such as attacking the queen or putting the king in check.

Evaluate each move objectively. You need to be looking at the entire board, evaluating every possible move you have. Don't make a move just because you have to—take the time instead to look for the best possible move every turn. What makes a good move depends purely on context, but there are a few questions you can ask yourself before every move to see if it is the right one: Am I safer than where I was before? Do I expose this piece, the king, or another important piece? Can the enemy quickly put my piece in danger, making me move back and "lose" a turn? Does this move put the enemy under pressure to react to me?

Take out your opponent's pieces as a unit. You want to maintain control of the center, but you also want to attack as a unit. Your pieces are like the parts of an orchestra; they each serve a unique purpose but work the best together. By eliminating your opponent’s pieces, you have a greater chance at putting their king in check without a piece to hide behind, and by doing it with 2-3 units as support, you ensure that you keep the advantage in material.

Protect your queen at all times with a bishop or rook. It is the most powerful piece on the board for a reason, and there are rarely good times to trade it in for an opponent's piece, even their queen. Your queen is your most versatile attacker and needs to be used as such. Always protect and support the queen, as most players will sacrifice just about any piece (other than their own queen) to take her down. Queens only reach their full potential with support. Most players instinctively watch the opponent's queen, so use yours to force pieces into the line of your rooks, bishops, and knights.

Don’t close in your bishops with your pawns. Bishops strike from long-range, and using the two of them to control the board is vital, especially in the early game. There are many opening strategies that you can learn, but the overall goal is to quickly open up space for your higher value pieces to move freely. Moving your pawns to either d4/d5 or e4/e5 opens up your bishops to move and helps you claim the center squares. Get the bishops out early and use their long-range to your advantage while developing rook and the queen.

Winning As an Advanced Player

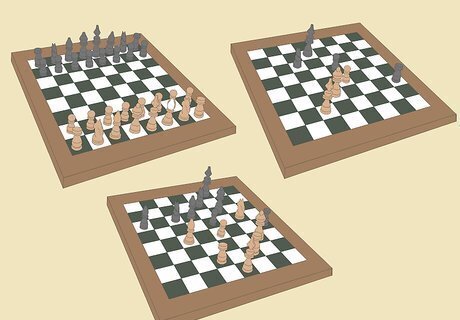

Think about the entire game from the opening moves on. A game of chess is generally considered to have three stages, all of which are deeply linked. The best chess players are always 10-12 moves ahead in their brains, developing 3-4 strategies simultaneously depending on their opponent's moves. They know that moves and pieces traded in the early stages will profoundly affect the game's end, and they plan accordingly. Opening: This is where you set the tone of the game. Your first 4-5 moves develop a lot of pieces quickly and begin fighting for the board's center. You can go offensive, taking the fight to them, or defensive, holding back and waiting for them to make the first move. The Middlegame: This exists purely to set up your endgame. You trade pieces, seize control of the middle of the board and set up 1-2 lines of attack that you can spring into motion at any time. A trade-off now may be beneficial, but you have to know how losing a piece affects your chances to win at the end. Endgame: There are only a few pieces left, and they are all incredibly valuable. The endgame seems like it is the most dramatic stage, but really most of the work has already been done—the player who "won" the middlegame and ended up with the best material should wrap it up with a checkmate.

Choose bishops over knights in the endgame. Early on, bishops and knights are roughly even in strength. In the endgame, however, bishops can quickly move across the entire, much emptier board, while knights are still slow. Remember this when trading pieces—the bishop may not help as much in the short-term, but they'll be an asset at the end.

Utilize your pawn's strength in numbers on an empty board. Pawns may seem useless, but they are critical pieces as the game winds down. They can support stronger pieces, push up the board to create pressure, and are a wonderful shield for your king. However, this benefit is lost if you start doubling them early on (put two pawns in the same vertical line). Keep your pawns close together and let them support each other horizontally. When there are very few pieces left on the board, a push upward to promote into a queen can win you the game. When behind in material, exchange pawns and go for a draw. If you are behind in material, exchange pawns because it increases your chances for a draw. If you exchange all the pawns and your opponent only has a bishop or a knight, he will not be able to checkmate you. If you are ahead, exchange pieces and not pawns. If you exchange all the pieces and you are ahead in pawns, it increases your chance of queening and winning the game. Pawns become more valuable as the game progresses so you want to keep them.

Know when to push for a draw. If you're down material, and you know you have no chance of getting a checkmate with what you have left, it's time to push for the draw. In competitive chess, you need to realize when you've lost the chance to win (you're down to a king, a pawn, and maybe 1-2 other pieces, they have you on the run, etc.) and should instead go for a tie. There are several ways to cut your loses and grab a draw, even when things seem hopeless: Perpetual check is when you force the opponent into a position where they cannot avoid going into check. Note, you don't actually have them in checkmate; you just have them in a position where they are not in check, but cannot move in a way that doesn't put them in check. Frequently done with a last-ditch attack on the king, leaving the opponent stuck between attack and defense. Stalemating: When a king is not in check, but cannot move without going into a check. Since a player cannot willingly enter the check, the game is a draw. Threefold Repetition: If the same position has repeated itself three times, a player can claim a draw.

The fifty-move rule: If 50 moves have occurred without a piece being captured or a pawn being moved, you can ask for a draw. Lack of material. There are a few scenarios where winning is physically impossible: Just two kings on the board. King and bishop against a king. King and knight against a king. King and two knights against a king.

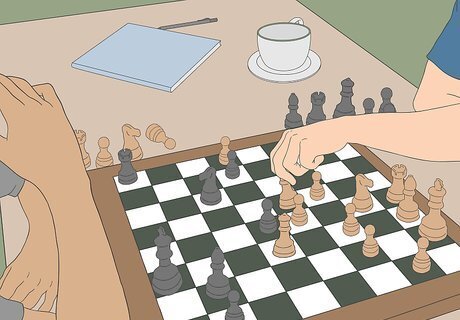

Practice some chess problems in your spare time. You can vastly increase your chess skills without ever facing an opponent. Chess problems are sample boards that ask you to get a checkmate with just 1 or 2 moves. You can practice on 100's of them in books, against any computer (the one with Windows 7 has 10 levels), or online, and over time you'll start to learn great piece positions and unexpectedly sneaky modes of attack. While you will, more likely than not, never see the exact situation on the board, chess problems develop your ability to see all potential angles of attack and how to best set up pieces. Look online for problem sets, or check out a book on chess strategy at the library, as they will all have practice problems.

Winning As an Expert Player

Learn to attack. Attacking is a great way to win more games. It has a huge effect on your opponent and can make them feel nervous. Try to detect your opponent's mistakes. If you think that your opponent made a mistake, start the attack. Don't start a premature attack without a prompt, though, as that can result in you losing the game. Attack their pieces, open the position, and try to attack with every move. It will get easier with practice. If there are no more attacking moves, improve your position and attack again on the next moves.

Confuse your opponent. If your opponent is confused, they will get frustrated and feel like nothing will work out. There are many ways to do this: Play an unexpected move. For example, if they expect you to play a particular move, see if you can play something else instead. Of course, don't play a move if it's bad, but search for good unexpected moves. Complicate the position. Increase the tension, don't exchange pieces, and try to get more piece contact. Though this may confuse yourself, it will become natural with practice, and you will win games.

Learn the principle of 2 weaknesses to use in the endgame and late middlegame. This is when you attack 2 weaknesses on opposite sides of the board. For example, you can attack a weak pawn on one side and promote a passed pawn on the other side. If there are no weaknesses, you have to create them. Start with a pawn break (when you make contact with the enemy's pawn using yours) and attempt to foresee what your opponent will do. Make sure your pieces are all helping out.

Prevent your opponent's plans. This technique can be found in many books and is a classic for beating master-level players. It is called prophylaxis. To prevent your opponent's plans, first find what they are. Think about what you would play if you were them. After you found a good plan for them, find a way to prevent it. Try to be as active as possible while doing this. Don't go into full defense mode.

Review the basic principles, rules, and ways of playing from time to time. Sometimes, getting stuck on the high-level techniques can make you forget the most important chess knowledge—the knowledge you learn when starting. Take notes during chess lessons. Later, you will be able to review the things you learned during the lesson.

Get a high-level or elite coach to train you. Getting a high-level coach is essential if you're an advanced player. Opt for grandmasters and international masters for high-level coaches. Try to find someone with a lot of experience. Listen to your coach. If your coach says to do tactics, do it. They are experienced in this area and know the right way around.

Comments

0 comment