views

X

Research source

By drawing a series of contrasts, you are able to narrow down the specimen until you can correctly identify it. Dichotomous keys are often used in the sciences, such as biology and geology. To make your own dichotomous key, first, select the characteristics you can use to contrast your specimens, then formulate these as a series of statements or questions you can use to narrow them down.

- Create a list of characteristics for the specimens you're trying to identify. For example, you might list traits like black fur, striped fur, spotted fur, long tail, short tail, and so on.[2]

- Focus primarily on characteristics that can be used to differentiate the specimens. If one specimen has fur and another has feathers, those would be good characteristics to list.

- Use the listed characteristics to divide your specimens into groups, like specimens with feathers and specimens with scales.

- Start with two groups, then divide each of those into two groups, and so on until each specimen is differentiated from all of the other specimens.

Analyzing Your Specimens

List the characteristics of your specimens. Start by considering the specimens you are trying to identify and insert into a dichotomous key. Note characteristics that define the things you are looking at, and start listing them out. If you are trying to create a dichotomous key for a series of animals, you might see that some have feathers, some swim, some walk on legs, etc. For example, if you are trying to differentiate a set of big cats, you might note that some are brown, some are black, some have stripes, some have spots, some have long tails, some have short tails, and so on.

Look for principles of exclusion. A dichotomous key works by the process of elimination, so you want to note characteristics that can be used to differentiate the things you are examining. For example, if some of the specimens you are looking at have feathers but others have fur, then “feathers” is a good distinguishing characteristics. However, a trait all of the animals share is not a good distinguishing factor. For example, since all big cats are warm-blooded, you wouldn't want to use that trait on your dichotomous key.

Determine the most general characteristics. You want to create a dichotomous key based on increasingly specific differentiations, so you’ll have to order the characteristics of your specimens from general to specific. This will help divide your specimens ever-smaller groups. For instance: When making your dichotomous key for big cats, you may find that some of the cats you are analyzing have dark fur, and some have light fur. You may also see that all of them have short hair. Finally, you see that some of them have long tails, but some of them have no tails at all. You would start your key with a question/statement about fur color. You wouldn’t need to ask a question about fur length, since all of the examples have short fur. You would follow up with a question about tail length, since tails are not common to all of the cats, and therefore are a less general characteristic.

Creating Your Key

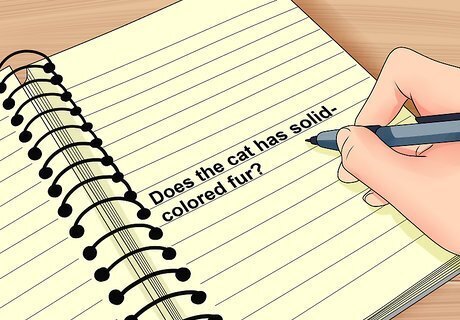

Formulate a series of differentiating steps. It’s up to you whether you want to use questions or statements, though you may find questions more intuitive. In either case, each question or statement should only break the specimens you are looking at into two groups. For example, "The cat has solid-colored fur” or “The cat has patterned fur” are statements that can be used to break specimens down into two groups. Include the question "Does the cat have solid-colored fur?” in your dichotomous key to divide the animals. If the answer is “Yes,” then the cat belongs in the solid-colored fur group. If the answer is “No,” then the cat belongs in the patterned-fur group.

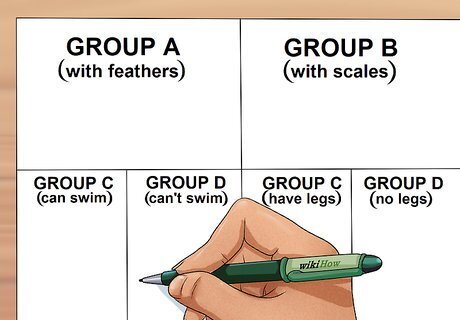

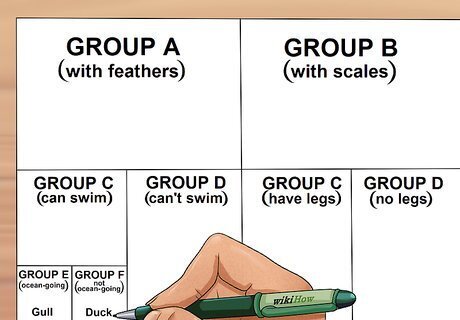

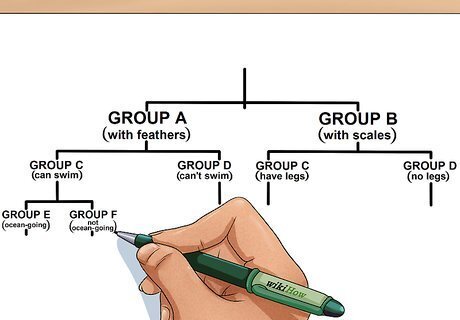

Divide your specimens into two groups. This will be the first differentiation. It should be based on the most general aspect of your specimens, so review the list of physical characteristics you developed. You can refer to the first two groups as A and B. For example, separate your cats based on whether they have solid or patterned fur. Similarly, if you note that all of your specimens have either feathers or scales, then these could be your groups A and B. You can begin your key with the question “Does the animal have feathers?”

Subdivide each of the first two groups into two more groups. Group A and group B will each be broken down into more specific groups (C and D), based on the next differentiating characteristic. For instance, you might notice that some of the animals in group A swim, and others don’t. This differentiation can form level C/D for group A. Likewise, you might see that some of the animals in group B have legs, and others don’t. This differentiation can form level C/D for group B.

Continue subdividing your groups. Keep formulating more questions or statements of ever-increasing specificity based on the physical characteristics you identified. Come up with characteristics that can break your specimens down as needed into groups E/F, G/H, etc. Eventually, you will reach the point until you have questions that only ask you to differentiate two specimens, and your key will be complete. Some specimens will be differentiated before the end, as you work through your contrasting characteristics. For instance, you might find yourself looking at some birds, and some reptiles. You will break them down into these groups, then sub-divide the birds. Two of the birds swim, but one of them does not. The single land bird will be identified as such, but you will have to further differentiate the swimming birds. In this case, you notice that one of the swimming birds is ocean-going, and one is not. This characteristic can allow you to identify them more precisely (e.g., as a gull and a duck).

Completing Your Dichotomous Key

Draw it out as a chart, if you want. A dichotomous key can be text-based, simply a series of questions. However, it can help to visualize the material in some way. For instance, you can create a “tree diagram” where each successive level of differentiation forms another branch of the tree. You could also try organizing your key in the style of a flow chart. For instance, have a box that asks a question like “Does the cat have dark fur?” Then, have a “Yes” arrow leading one way, and a “No” arrow leading another way. The ends of the arrows can lead to new boxes where you ask the next questions.

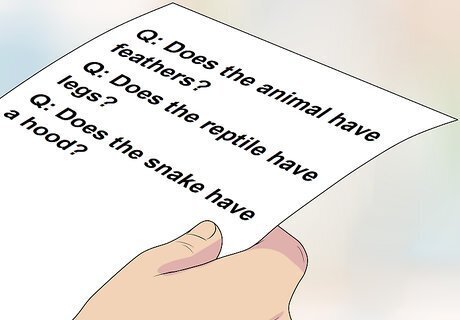

Test out your dichotomous key. Once you have all of your information down and organized in your key, run through the key with a specimen in mind to see if it works. For example, say you have a dichotomous key that helps identify various animals. Take a specimen and work through the key’s questions until it leads you to an identification through the process of elimination: Q: ”Does the animal have feathers?” A: “No” (it has scales, so it is a reptile). Q: “Does the reptile have legs?” A: “No” (it is a snake, either a cobra or a python, given your specimens). Q: “Does the snake have a hood?” A: “No” (so it is not a cobra). Your specimen is identified as a python.

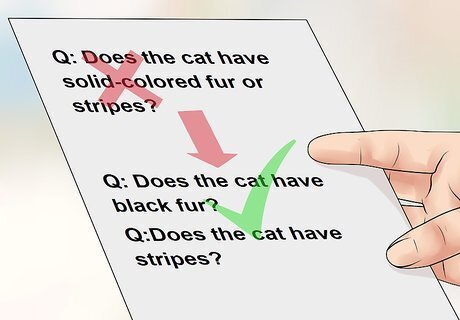

Troubleshoot, if necessary. You might find that your key isn’t working correctly, and need to adjust it. For instance, you may not have ordered your questions in an increasingly more specific way, and might need to reorganize them. Likewise, your key might not break your specimens down in the most logical way, so try reframing your questions. For instance, "Does the cat have solid-colored fur or stripes?” is not a useful question for a dichotomous key. This question might differentiate solid-colored and striped cats from cats with spotted fur. However, since solid-colored and striped fur are themselves very different, this is not a useful category to work with. Instead, you might first have a question that asks about solid-colored vs. patterned fur, then follow up with another level of questions like “Does the cat have black fur?” and “Does the cat have stripes?”

Comments

0 comment